Throughout summer 2020, this site gathered digital content that built upon the entire exhibition—new virtual tours of Wrightwood 659 and the Smart Museum of Art, object chats, at-home activities, online programs, and behind-the-scenes videos and photos.

From gunpowder to human hair, and silk to cigarettes, contemporary artists working in China have experimented with various materials, transforming seemingly everyday objects into large-scale artworks. The Allure of Matter showcases these material transformations and explorations for the first time.

Art and Materiality Symposium

February 7–8, 2020

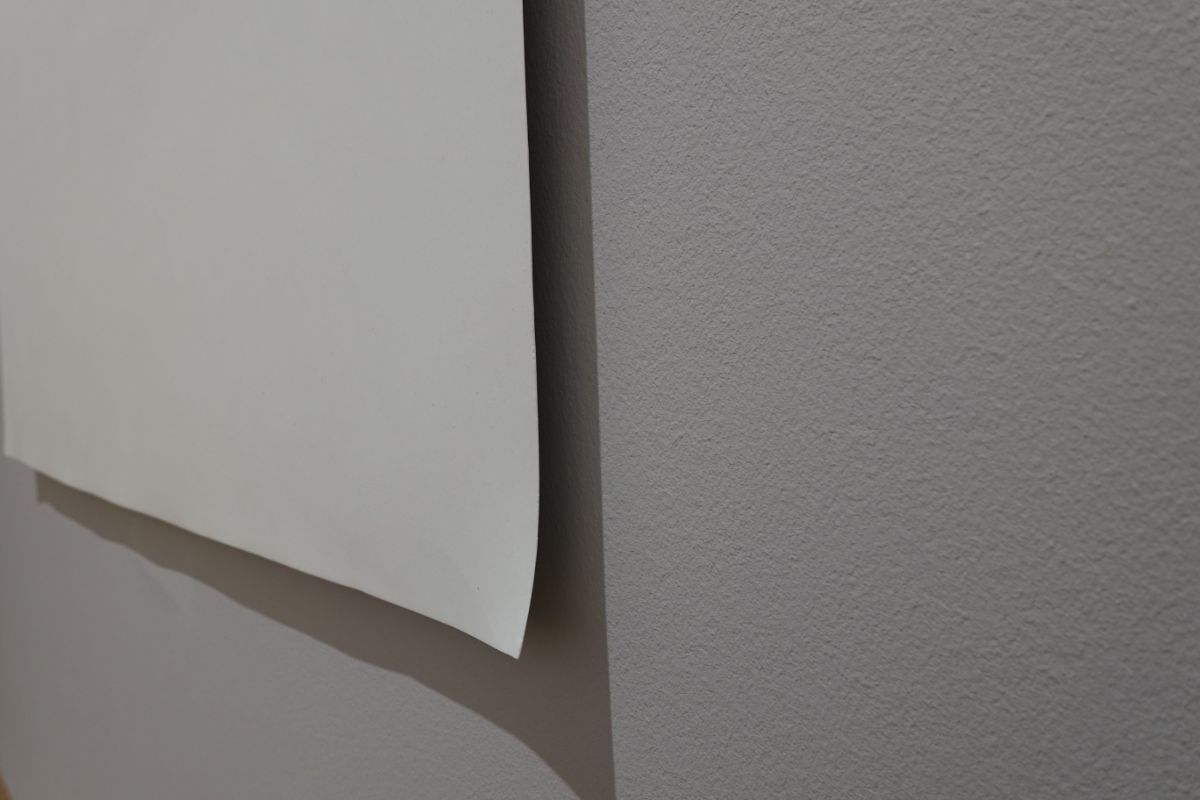

/ Song Dong, Water Records, 2010, and Traceless Stele, 2016. Installation view, The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2019–20. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

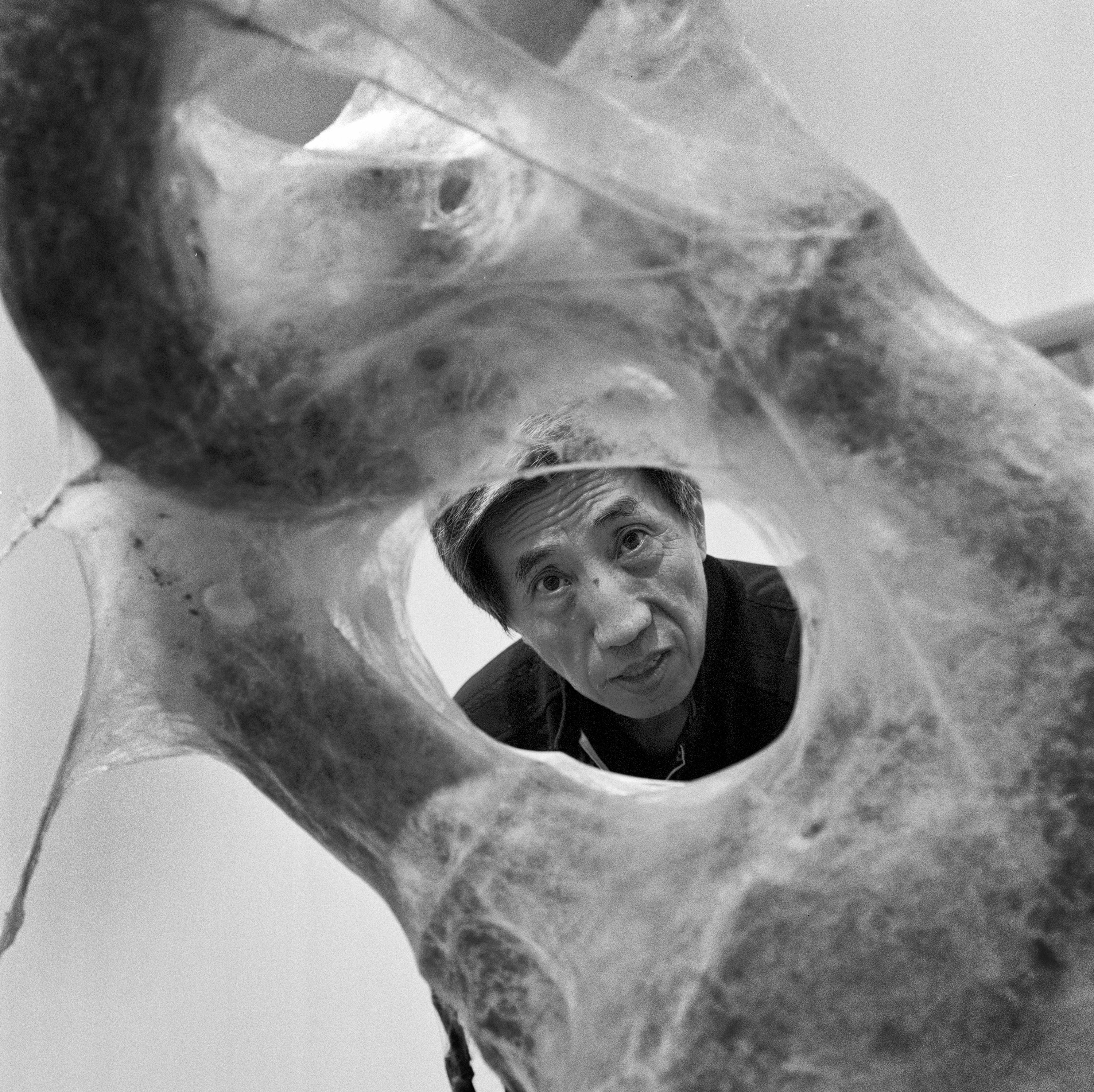

/ gu wenda, united nations: american code, 1995–2019. Human and synthetic hair, dimensions variable. Installation view, The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2019–20. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

/ Liu Jianhua, Black Flame, 2017. 8,000 flame-shaped porcelain pieces, dimensions variable. Installation view, The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2019–20. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

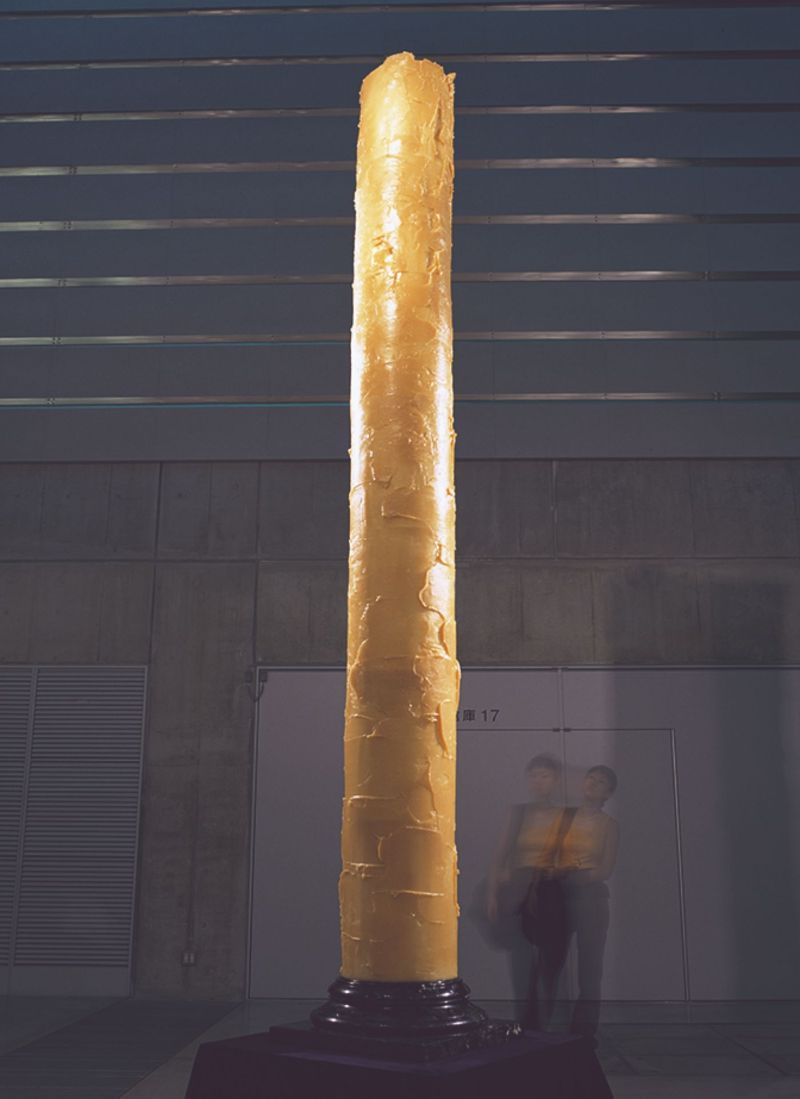

/ Gu Dexin, Untitled, 1989. Installation view, The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2019–20. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Through panels and presentations, an international array of eighteen scholars and artists build on the foundation of The Allure of Matter, connecting the concept of materiality to Chinese art historically, and to contemporary art globally.