Hello, welcome to The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China at the Smart Museum of Art.

I’m Wu Hung. I’m a professor of Art History at the University of Chicago, and a curator. I conceived this show, and coined the term of “Material Art.”

Since the 1980s, artists working in China have experimented with various materials, transforming seemingly everyday materials into large-scale artworks, to express their reflections and social conditions and the social transformations surrounding them. “Material Art” is a particular art form that involves an artist’s consistent use of unconventional materials to produce works in which material manifests the work’s meaning.

I hope you really enjoy the show.

I’m Orianna Cacchione, curator of Global Contemporary Art, and I am going to take you on a tour of the exhibition today.

Entering the Smart Museum, there are three works that embody “Material Art” in different ways, starting with Cai Guo-Qiang’s Mountain Range.

Although Mountain Range is a relatively recent piece, Cai Guo-Qiang is one of the first artists to experiment with “Material Art.” Cai began using gunpowder, making explosions on canvas and paper which gave him a sense of liberation from the confines of the paint and the brush that he had learned in art school.

Gunpowder is rich with cultural associations and political history – it was invented in China as an immortality elixir, and later transformed into a weapon by Europeans. He is able to skillfully apply the gunpowder to create careful, detailed drawings that are at tension with the inherent spontaneity and uncontrollability of each explosion. He also uses different types of gunpowder to create different “brushstrokes,” mimicking the characteristics of Chinese ink painting.

Lin Tianmiao is known for her work with thread – binding and connecting everyday objects. This practice was inspired by childhood memories of winding white thread from used cotton gloves that could then be repurposed to mend clothes, knit sweaters, and make doilies. As a child, Lin resented this work – the mundane repetition, but also the violence that it imparted on women’s hands and their bodies.

Here in Day-Dreamer, each thread hangs down from Lin’s own self portrait, creating a ghostly silhouette on the bottom mattress. The repeated placement of threads becomes a meditative act that sublimates her memories of punishment and violence.

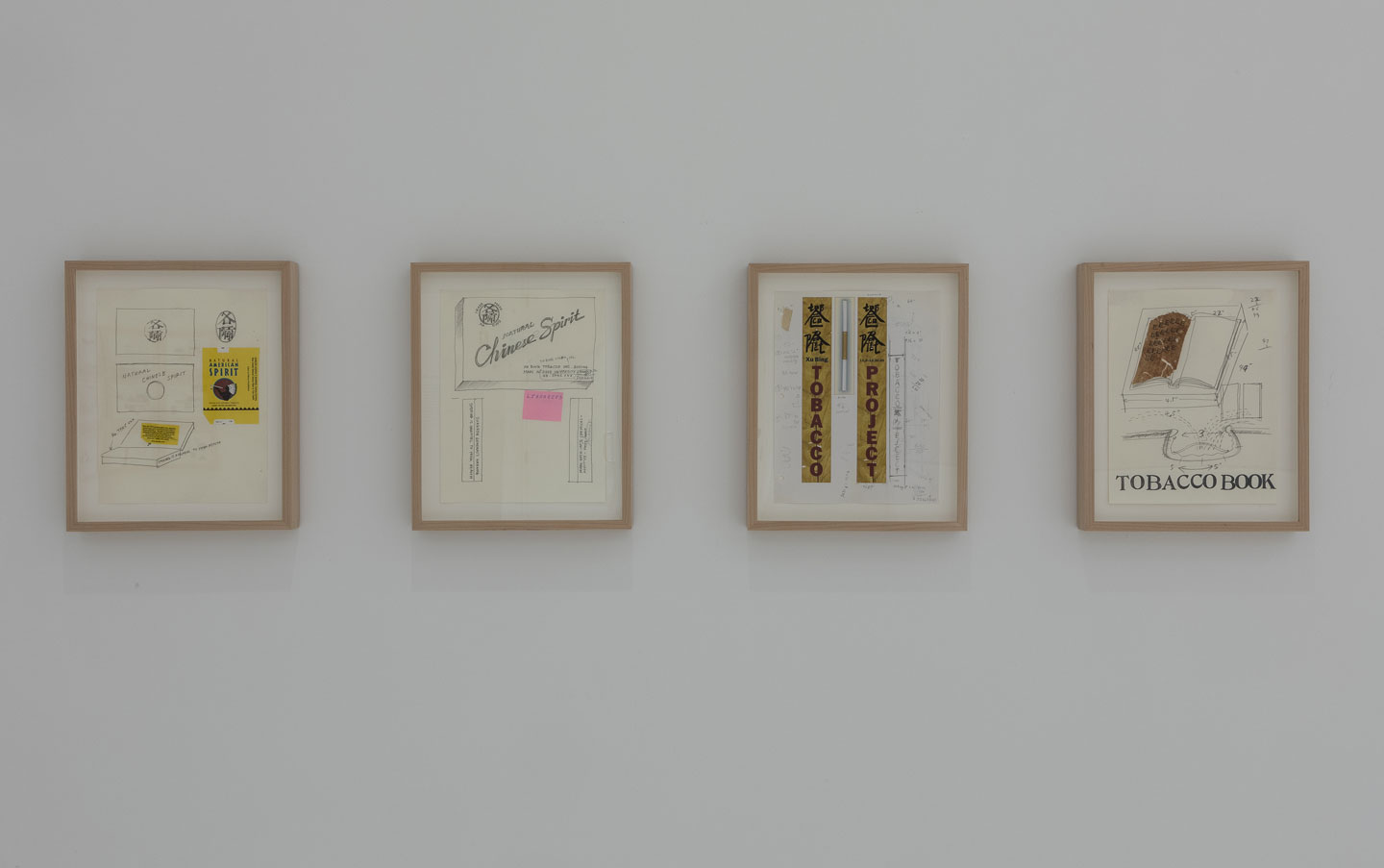

At the Smart, we have on view four sketches and three artworks from the Tobacco Project.

In 2000, Xu Bing was invited to do a residency at Duke University. Upon his arrival in Durham, North Carolina, he was struck with the ever-present smell of tobacco in the air. Intrigued, he began researching the history of the tobacco industry in the United States, particularly the American Tobacco Company’s expansion to China.

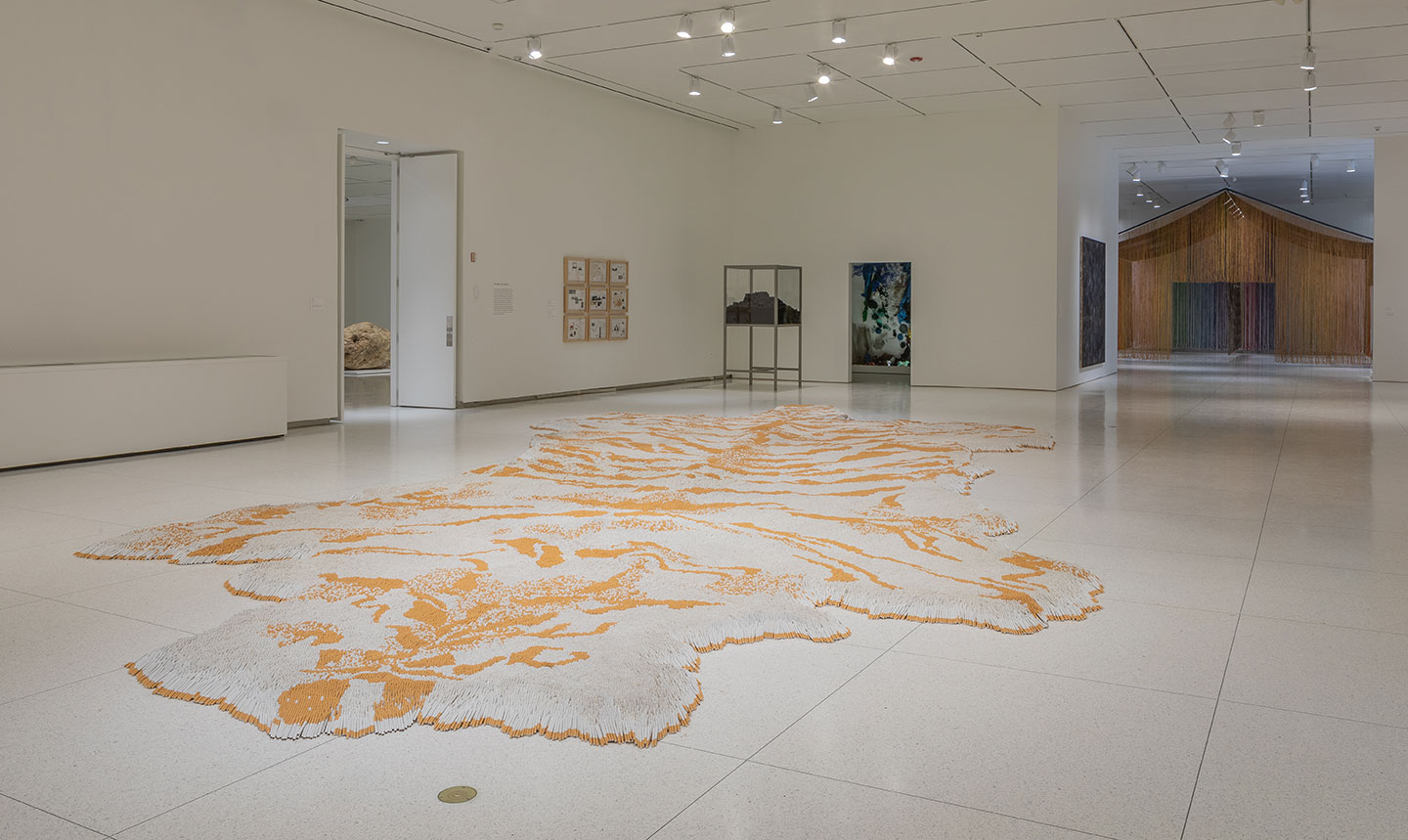

First Class is made from over 300,000 cigarettes, each carefully placed to create a larger-than-life tiger-skin rug – as you walk around, the colors change emphasizing the materiality of the cigarettes. Like Xu Bing’s first experiences of Durham, the massive rug emits a potent smell of tobacco throughout the gallery. Inspired by a photograph of a tiger-skin rug hanging in a colonial residence in Shanghai, it alludes to the circulation of luxury goods.

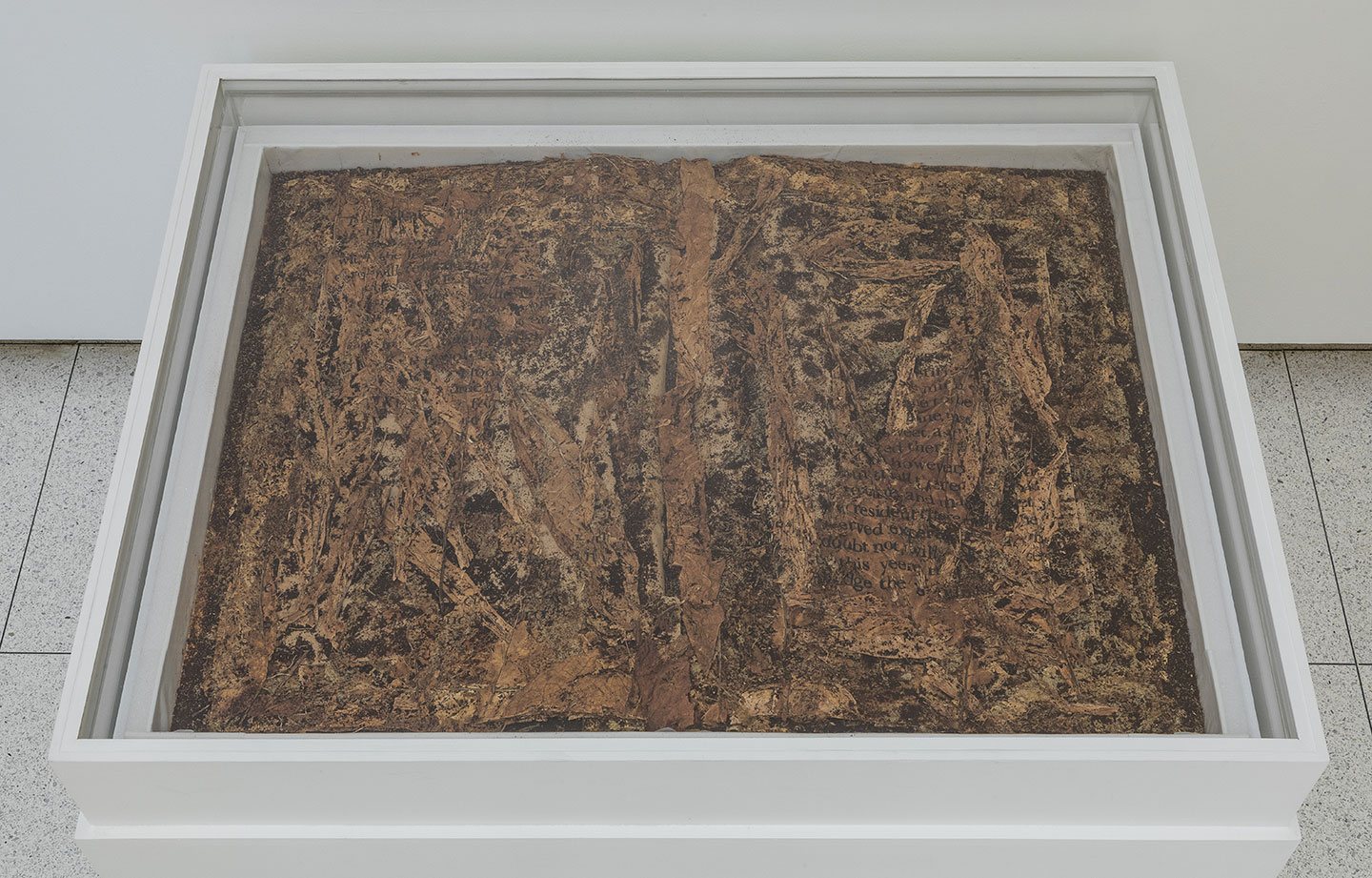

For Tobacco Book, Xu Bing printed parts of A True Discourse on the Present State of Virginia, written by Ralph Hamor in 1615, onto cured tobacco leaves.

The book describes the American Tobacco Company’s business operations in the British colony of Virginia and its expansion to China, in a propagandistic fashion. Once he finished making the book, Xu Bing sprinkled tobacco beetles that gradually ate through the pages, consuming the history of the expansion of the tobacco industry to China.

A long, hand rolled cigarette was burned onto of the famous Song Dynasty handscroll, Along the River during the Qingming Festival. Imprinted into the scroll, a charcoal scar suggests the irreparable damage caused by smoking, but also the passing of time.

Like cigarettes, Coca-Cola has been ubiquitously marketed and sold around the world. For the Cola Project, artist He Xiangyu deconstructed and destroyed the sugary drink by boiling down 127 tons of soda into a sweet-smelling burnt ash. Here the remains are piled into a vitrine – transforming the desiccated substance into exalted art object. Along the wall are sketches that document He Xiangyu’s process, receipts from the Coke that he purchased, old advertising materials, and possible projects. Like Xu Bing’s Tobacco Project, the Cola Project considers the international circulation of commercial goods, although here He Xiangyu’s critique is biting, the once sweet drink is destroyed, leaving only the sticky ash remains.

In the early 1980s, self-trained artist Gu Dexin began working in a plastics factory. From the factory, he took home scrap pieces of plastic, burned and melted them in his kitchen, creating blobs that he would hang on the wall.

From these early home experiments, Gu Dexin was invited to create a new work for Magicians de la Terre, an exhibition of global contemporary art held in Paris in 1989. There, for the first time, he was able to fill entire room with melted, molten plastic – creating his first immersive environment. The plastics he used were both purchased materials and junk he found discarded on the street. Despite the chaotic impression the room gives, each piece was carefully handled, sculpted. For Gu Dexin, art was about experience not meaning, evoking a direct response in the viewer.

From artworks that exemplify the destruction and transformation of the material, we shift to a pair of works that are connected not only because of their physical materials – here, wooden tables – but also, their conceptual questioning of history.

Ai Weiwei is perhaps best known for his recent political activism, but his early works were characterized by a profound questioning of Chinese history. In the early 1990s, he began collecting and manipulating Chinese antiques that were readily sold in markets throughout Beijing. Ai Weiwei was fascinated with how the value of these supposed antiques was not intrinsically part of the object but rather culturally constructed. His iconoclasm was further provoked by the ways the Chinese government frequently re-wrote history and the value of historic objects.

On the other hand, Huang Yong Ping consistently questioned grand historical narratives, especially those of national or geographic heritage. Should We Build Another Cathedral? responds to a question asked during a conversation between famous post-war European artists – shown in the photo above the table. Huang Yong Ping’s response is the remains of books about those artists that have been washed in a washing machine. Years earlier, Huang Yong Ping began making artworks using what he called the “wet method.” He would take books and washing them together in a washing machine, physically transforming them into a wet pulpy mess. For Huang, the “wet method” made culture dirty, questioning the need for cathedrals at all.

Made with black pantyhose stretched over concrete board, Ma Qiusha’s Wonderland: Black Square contains a biting tension between the fragile pantyhose as they run against the jagged points of the concrete. Sparked by a childhood memory of women’s pantyhosed legs riding on bikes by her house, for Ma Qiusha, the pantyhose embody different generations of women in China. Her mother’s generation could only buy nude colored hose, but later, women could buy white and black. And now, you can order any color on the internet. These changes demonstrate the shift toward capitalist consumerism and question the possibility of collective identity.

At the end of gallery, three works demonstrate different ways the body can be used as both material and object.

Since the early 1990s, gu wenda has used human hair as his signature material in his ongoing united nations series. Here, thousands of feet of multicolored hair braids make the outside structure of a house. Inside hangs a flag. The flag is a composite of a star and stripes composed of different pseudo-languages. The braids and hair are taken from hundreds of people, from different places, and with different backgrounds, emphasizing transnationalism, transculturalism, and hybridization. The work’s subtitle – american code – speaks to the diversity of the American population captured in the many thousands of people’s DNA, represented by their hair woven together.

Made by the artist duo, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu, Civilization Pillar is made from human fat that has been mixed with wax and Vaseline until it is formed into a towering column. The fat was collected from liposuction clinics throughout China. For the artists, fat represents the excesses of contemporary society – in this case, it is intentionally removed from the body for extravagant prices. Here, it becomes a monument to contemporary civilization’s overconsumption.

Evoking the Daoist concept of “internal alchemy” – a healing practice where the interior of the body is visualized as a way to purify it from illness or toxins – Chen Zhen has carefully cast his internal organs in clear translucent crystal. One of the last works he made before his untimely death from cancer, the work evokes Chen Zhen’s own musing: “When one’s body becomes a kind of laboratory, a source of imagination and experiment, the process of life transforms itself into art.”

In the back galleries, the artworks on view contrast different materials – permanent and fleeting, hard and soft, real and fake, creating a quieter, more contemplative space.

Since the early 1990s, Song Dong has used water as a subversive material – one that leaves a temporary trace before disappearing forever. Four video projections fill the walls of the gallery. They capture Song Dong drawing with water – a mountain range, the profile of a man, a bar code – he is barely able to finish one gesture without the earliest strokes evaporating. Also in the gallery is Traceless Stele. Stele were historically used to memorialize important events and record philosophical texts. Once this information was carved into the hard stone, people could make rubbings of the texts, effectively transmitting the information contained within the stone slabs. Here Song Dong inverts to typical conventions of the stele. He invites viewers to write on this blank stone in water – as the water slowly evaporates any trace of the text or drawings vanish, its contents committed to memory or secrecy.

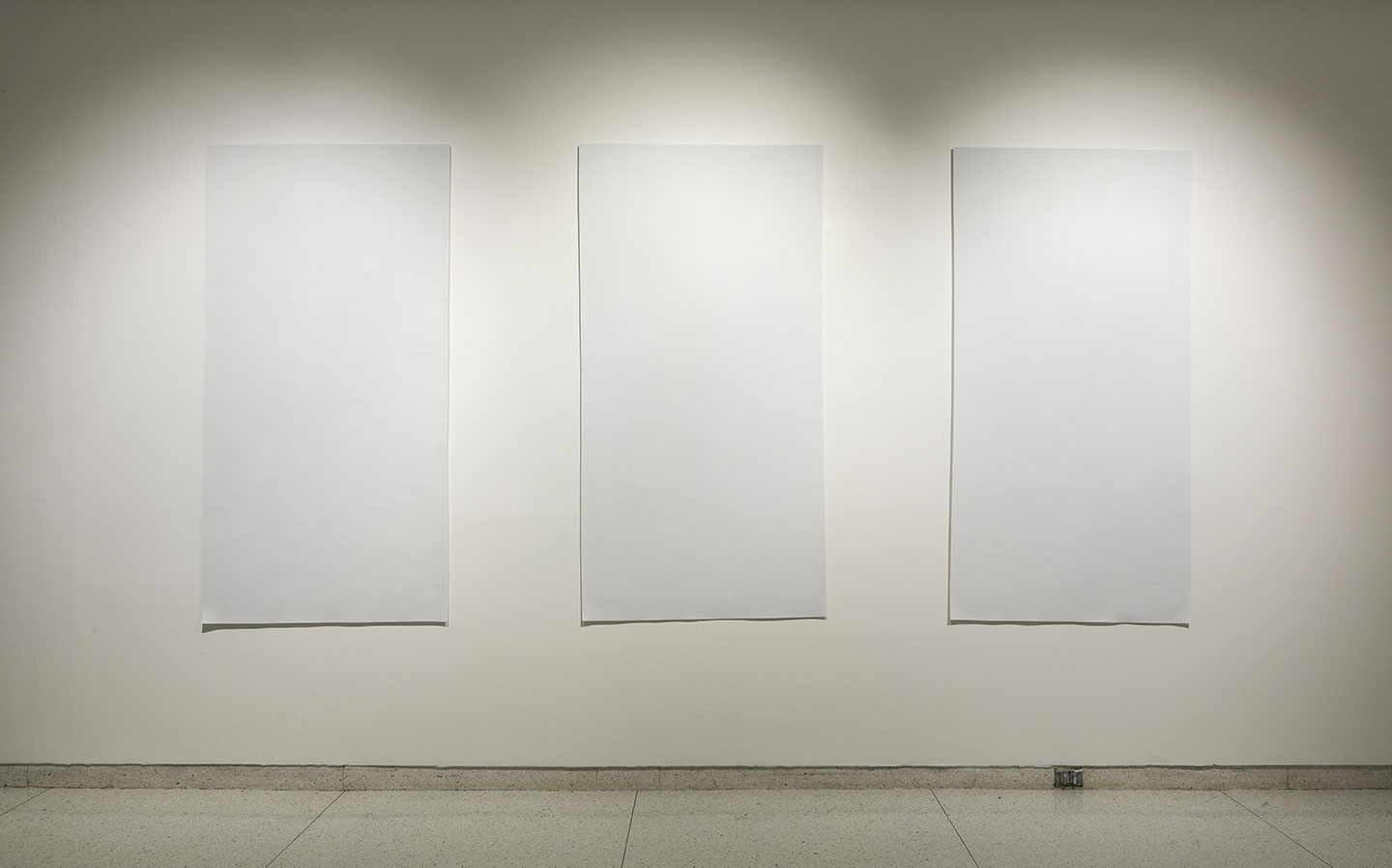

Teetering between one thing and another, this work isn’t what it immediately seems. The three blank papers that hang from the wall are actually made from the thinnest sheets of unglazed porcelain. While this seems like a simple task, it is actually extremely difficult and demonstrates the masterful command Liu Jianhua exerts over porcelain production. Unglazed and blank, the “papers” hang quietly in front of you, shifting any contemplation of the object from its surface to your mind.

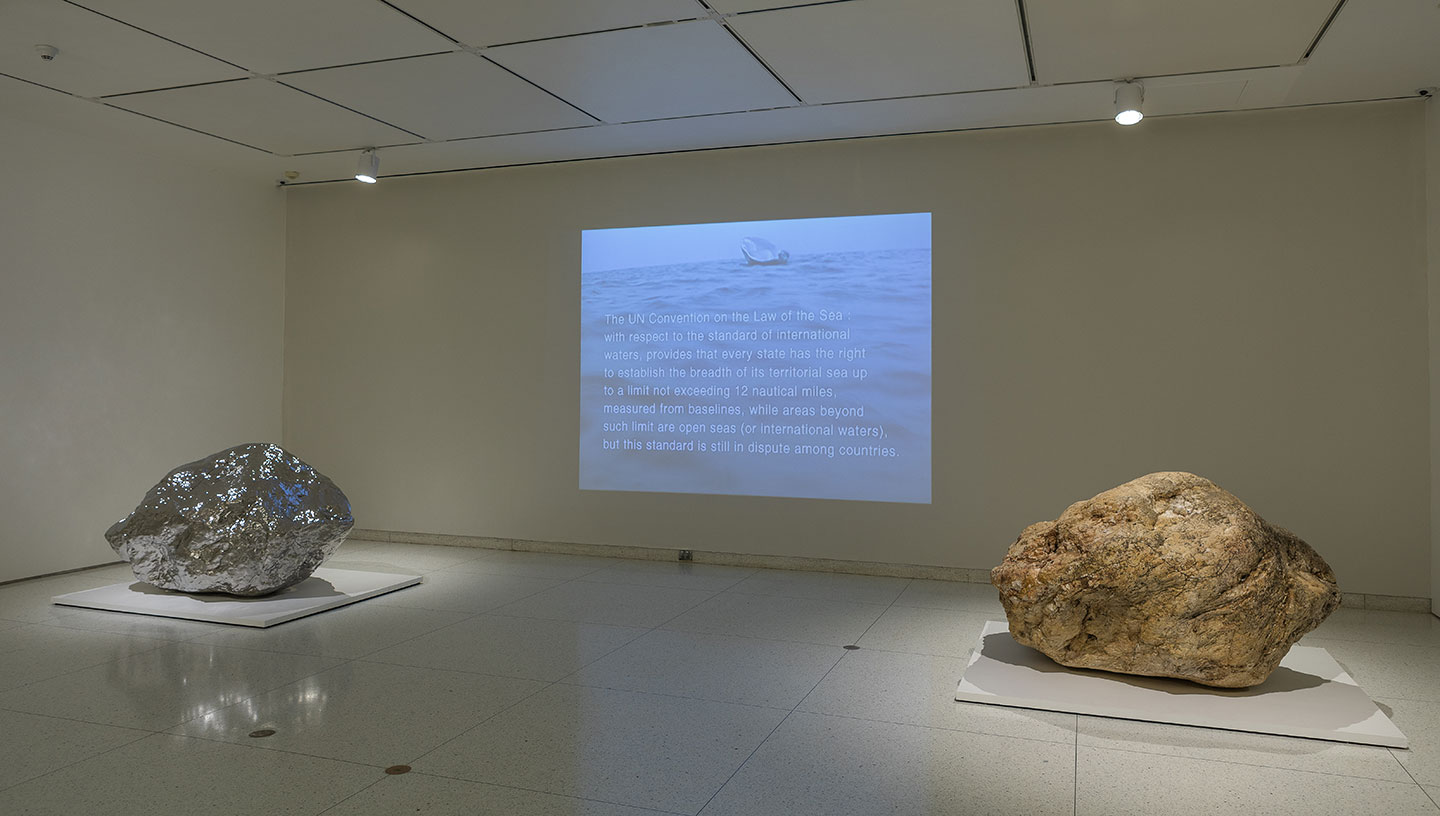

In the video, Beyond 12 Nautical Miles, Zhan Wang playfully tests the borders of international water. He set afloat a hollow stainless-steel rock 12 nautical miles beyond a Chinese beach. As the rock rootlessly floats in international water, Zhan Wang evokes recurrent disputes over national claims of territorial boundaries. Just in front of the video is a second work – Golden Mountain – composed of a rock mined from the Sierra Nevada Mountains and its stainless steel copy. During the Gold Rush, Chinese immigrants traveled to San Francisco to pan for gold in the mid-19th century. The title comes from the Chinese name for San Francisco – jiu jin shan – literally Old Gold Mountain.

In the Smart’s lobby hangs Zhang Huan’s Seeds. The painting is made from incense ash that was collected from temples throughout China. The artist’s studio assistants then carefully sort the ash into varying shades of grey that is then used to “paint” a near photographic representation. The ash forms the image of collective farming, that was taken from Mao-era magazines that would have celebrated this collective effort. However, here the monochromatic image casts a cold ambivalent gaze at this moment in history. Despite the government’s attempts to modernize the country through collectivism, many of these projects failed. For Zhang Huan, the incense ash, like the photographs he uses as source material, represent collective memory, here when put together they question how this history has impacted the national psyche.

Thank you for joining me on a tour of The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China at the Smart Museum. The other half of the exhibition, originally on view at Wrightwood 659, is also available as a virtual tour at theallureofmatter.org.