Because there were flea markets near my place, when I had free time I would go look around. I’d see a nice sofa and buy it, or a handsome doorframe. Of course for doorframes, like for this one, I might use it [for my artworks] as well. I would keep many traces that are on it. Today I wouldn’t do that, but at that time I would preserve it, like if a window has a picture pasted to it. I think that’s interesting, beautiful. It’s something very special. I don’t want to say it’s a story, but I think it has some beauty. I would abstract it, completely abstract it. It’s just something very beautiful. I would preserve what’s on the window, or what’s on the wall. I would preserve it, but not because I want to tell a story, or to say something like, oh this person once lived here and had this kind of life—I never think this way. For me, it’s already become abstracted. In the end I don’t think anything is necessary. No need for concepts. It just needs to be filled. I just need to fill this form with wood and materials so you can’t see anything; the only thing that’s left is time.

In Beijing at the time, my studio was located around the outskirts, where the city met the village. At that time there were many people—now probably less—but at that time migrant workers came to Beijing, and they would live around the edges of the city, and it was quite a dense population flow. People living there had their own way of life. It’s what got me interested.

All the materials are things they would use in their daily lives. For me, I’d go to the flea market. I think, this thing, the flea market . . . they may sell a window, sell this kind of thing, or furniture. I think some people . . . I don’t think that window is what they really want to use, but it’s what they use everyday. The materials I use are this kind of material: windows and doors. Really some things I go to buy, and I’ll buy it, and then bring it back and actually use it, because it looks good. Like old furniture. I have many old things. Their texture is entirely different. For example, if I buy something made of stainless steel or aluminum, I will buy a new one. For this I need a shape. But if I used something new, the feeling would be different; with age their texture completely changes.

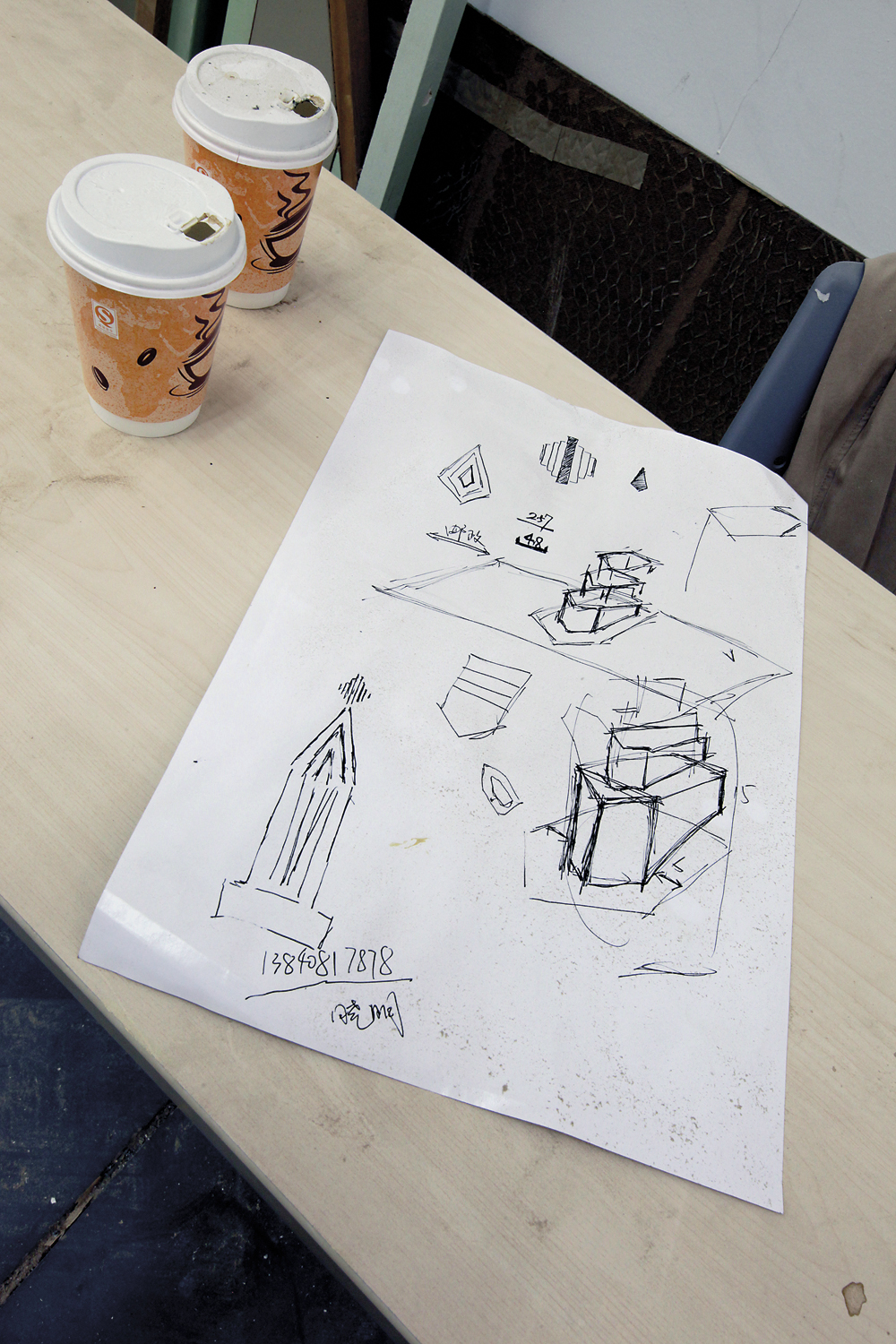

For me, a very important aspect of making an artwork is that I have to have a reason. I need a starting point to do it, and a stopping point is also important. That’s why my working process is like this: When I’m in my studio working, I need to see the work. I won’t draw a drawing, get it made, and it comes back as a readymade. I won’t do such a thing because I think art—artworks—are different from products for that reason. I’m feeling it. I’m with it every day, feeling it. I might not be the one making it, but I’m present, continuously feeling it, even when the studio assistants are the ones working. I only give my assistants an approximate direction in which to follow. And they do the work according to their own understanding.

So why is it called Merely a Mistake? Because I think it all stems from my misreading of reality, including my visual misreading of the things that I see. I think it’s an abstraction, and I think it’s important. It’s important for contemporary art that we have an abstract way of seeing the world. What we need is a link, rather than a specific thing. Like when I see an image, I won’t try to discover what this image actually is. The image I see is you and the wood, just this kind of picture. I won’t consider that you are a human body with various structures, or what’s going on with the wood. I don’t need all that. I’m not like that. I just look at this image and what I see is what it is. It may be all wrong, but all these misreadings can create something new, I think.