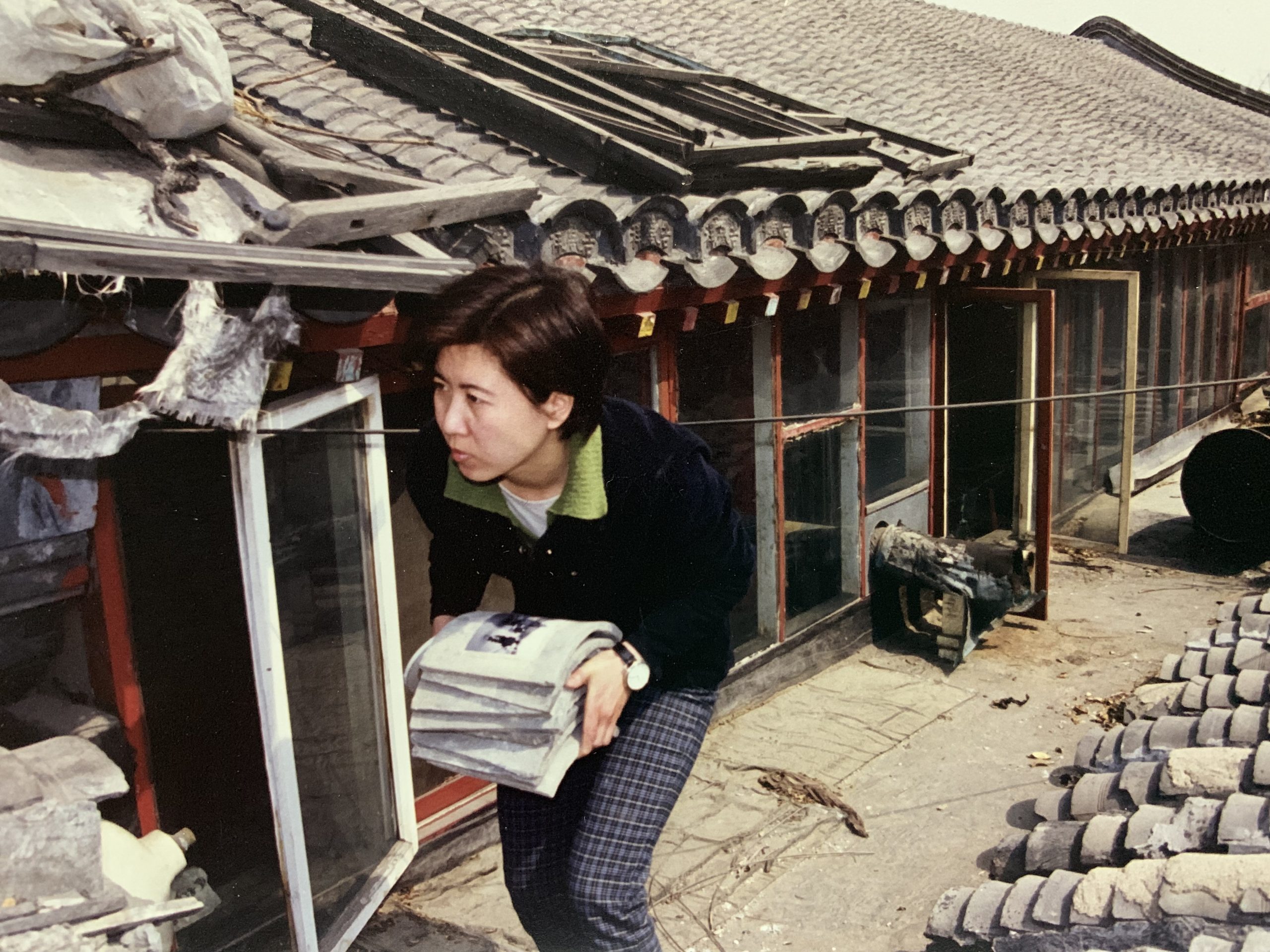

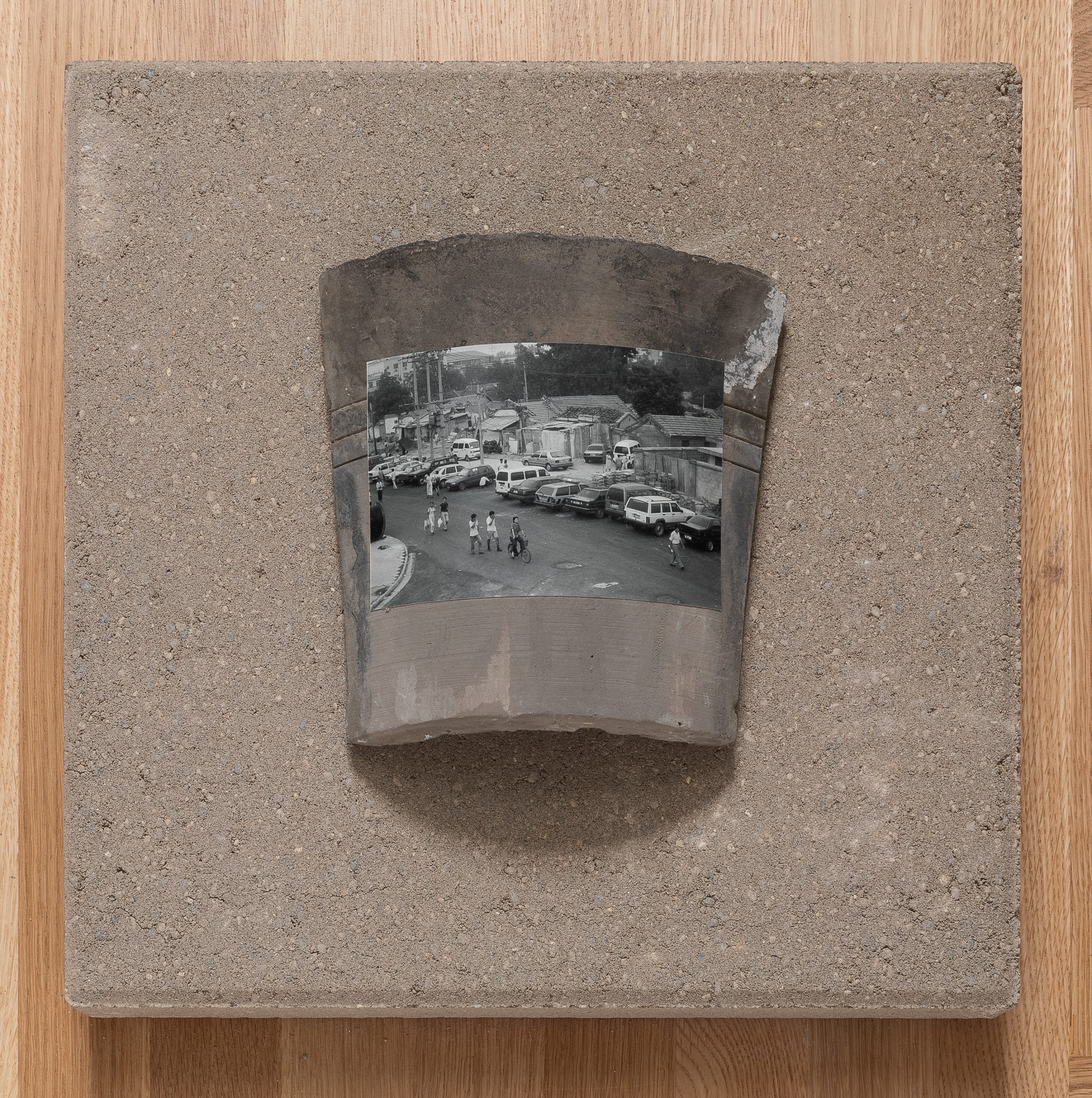

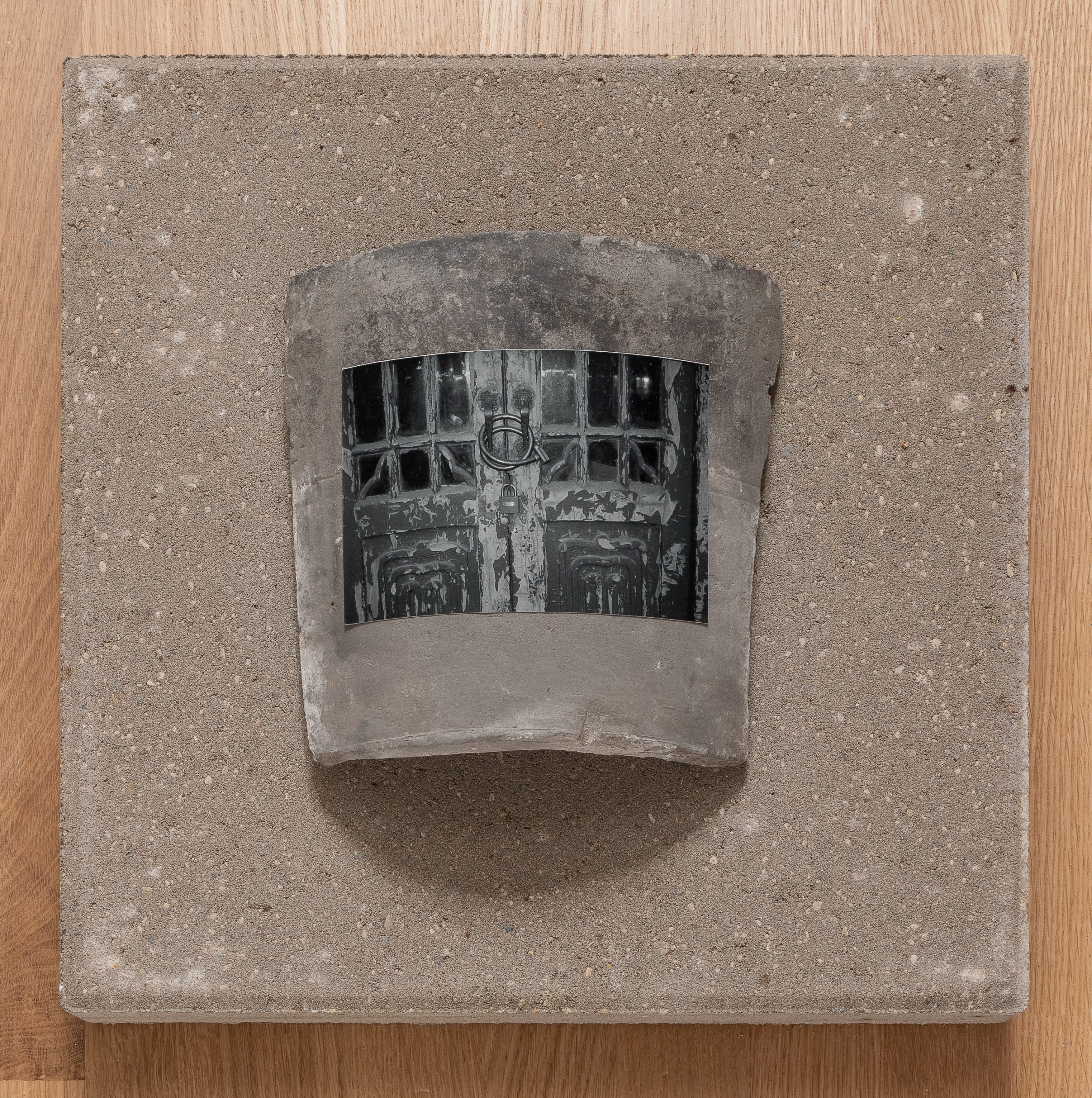

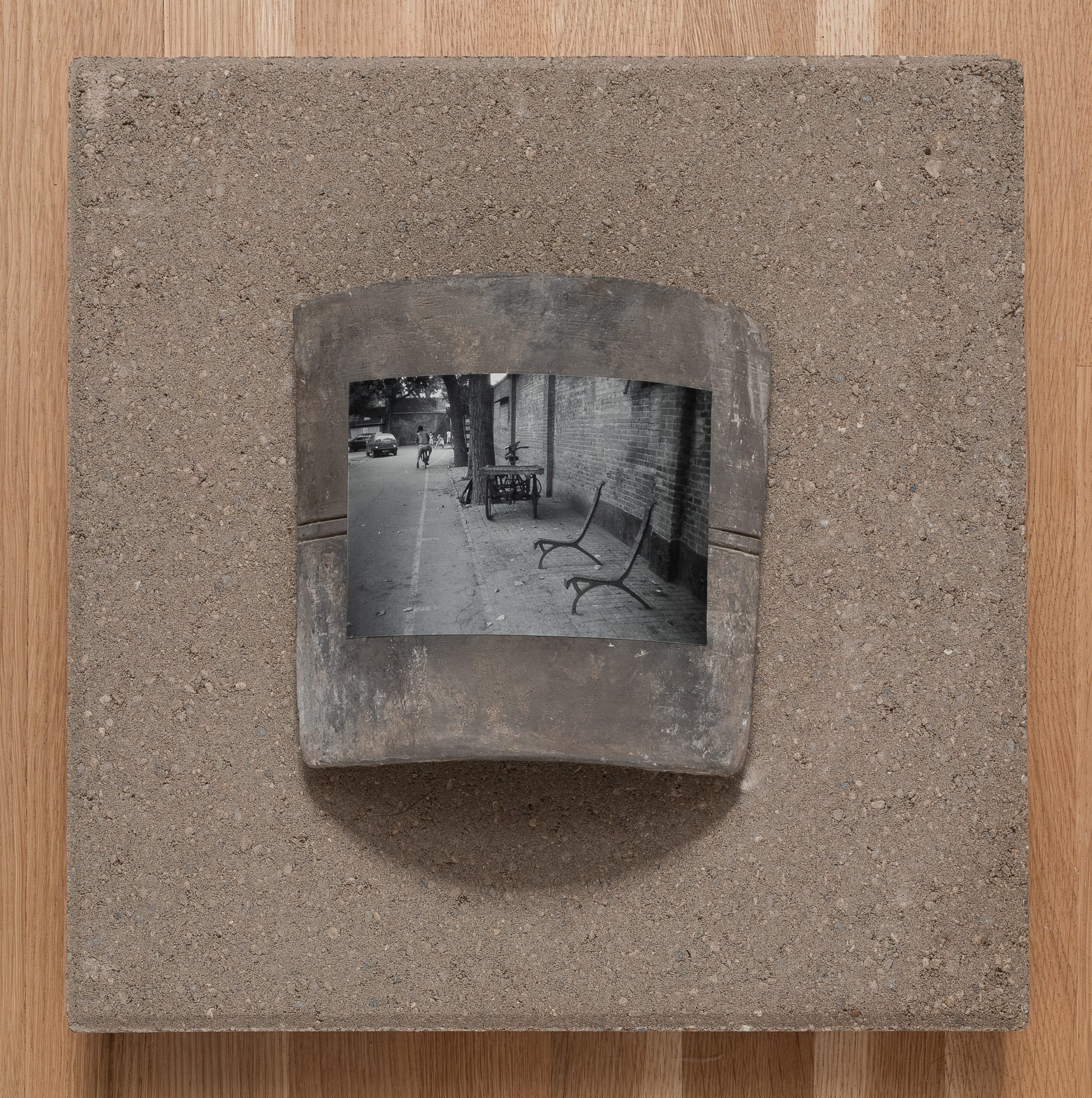

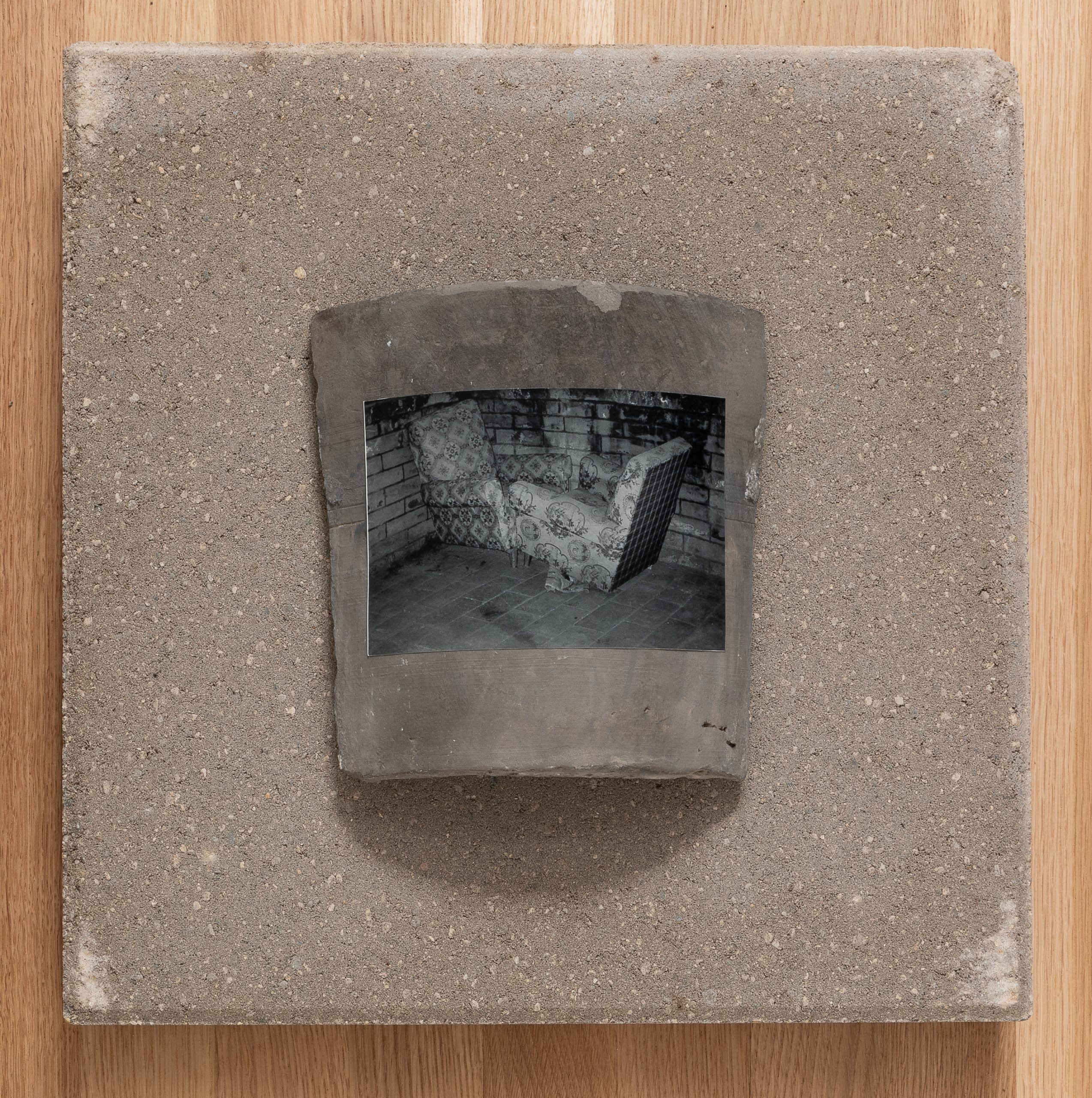

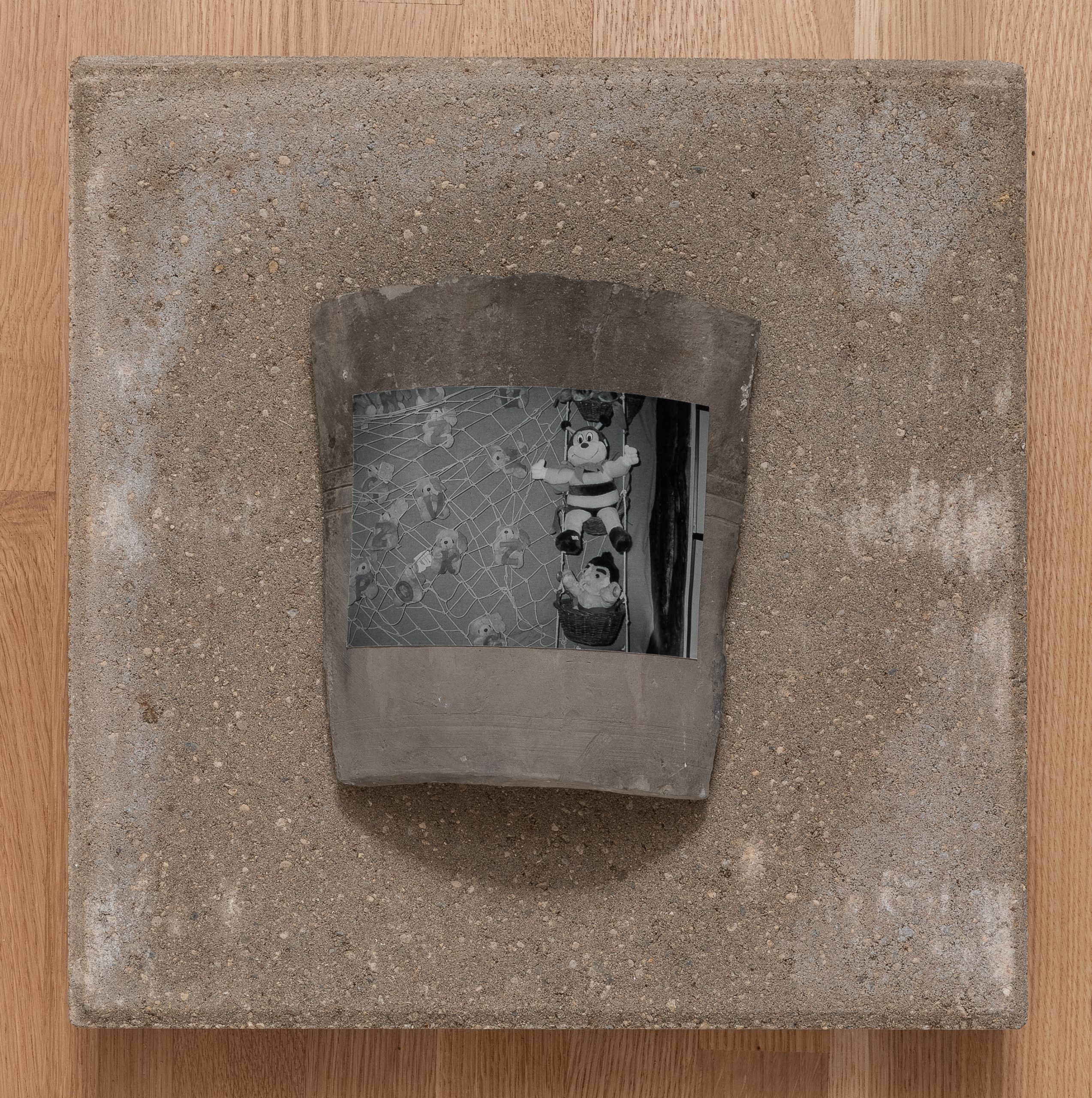

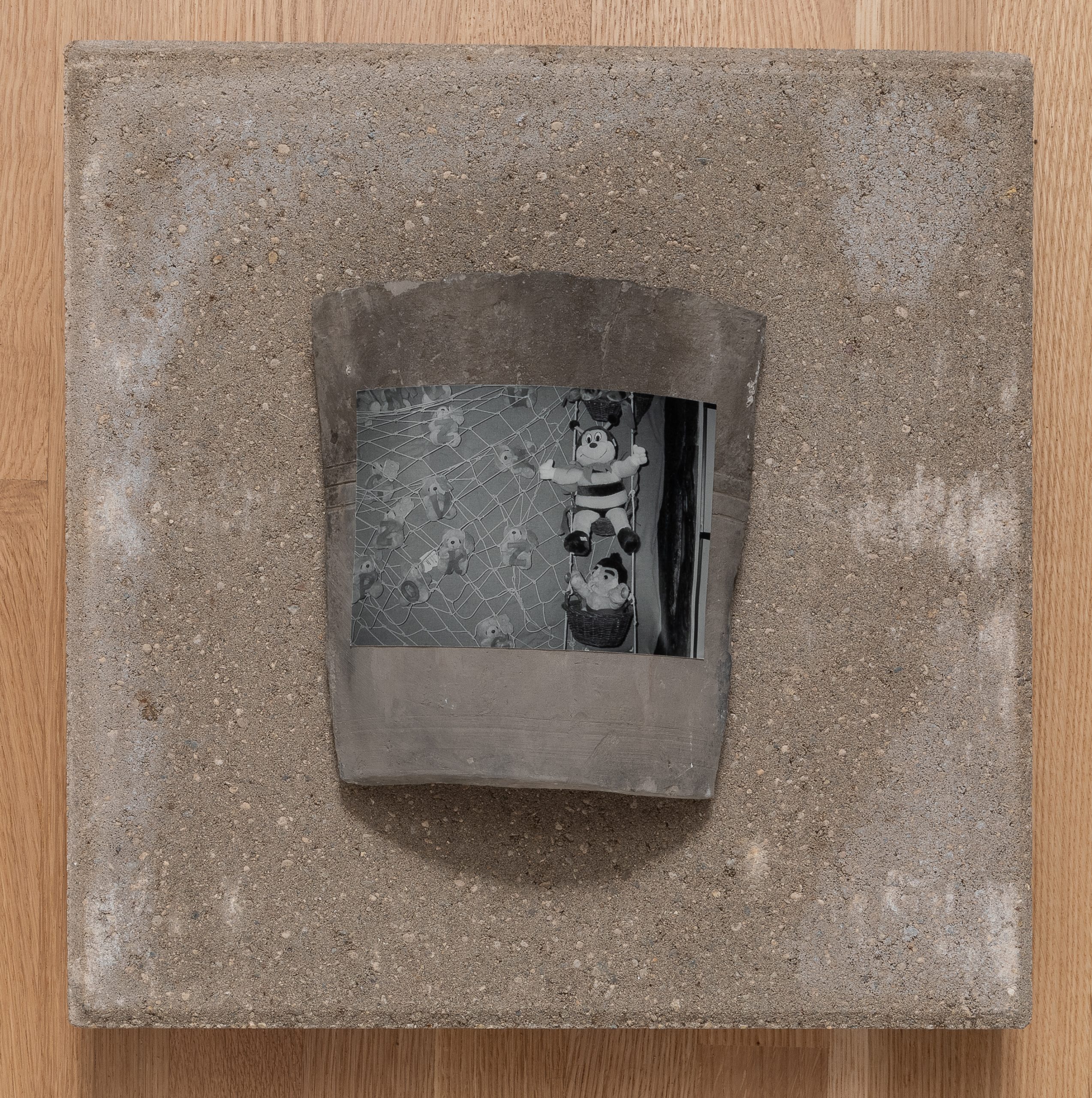

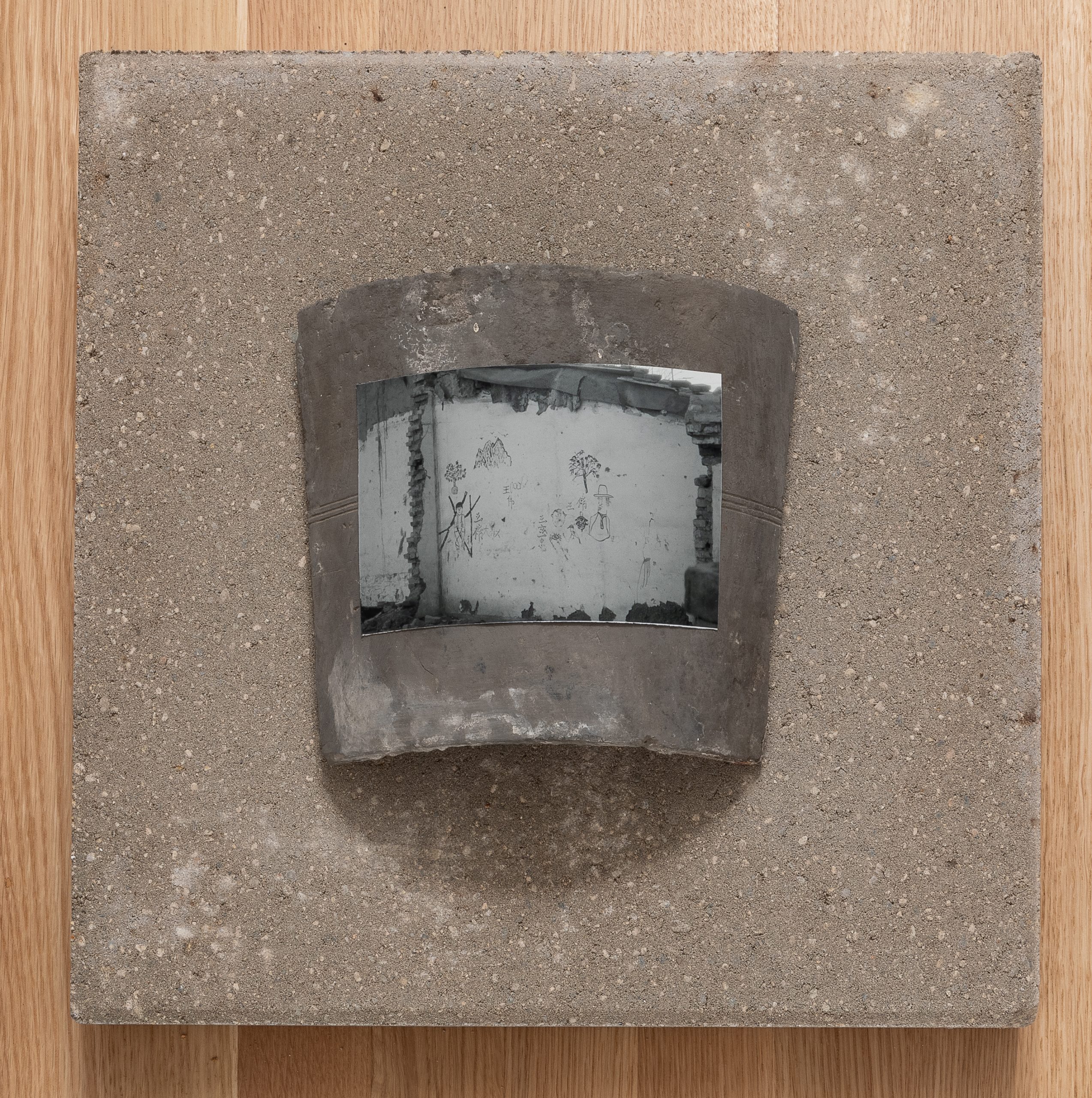

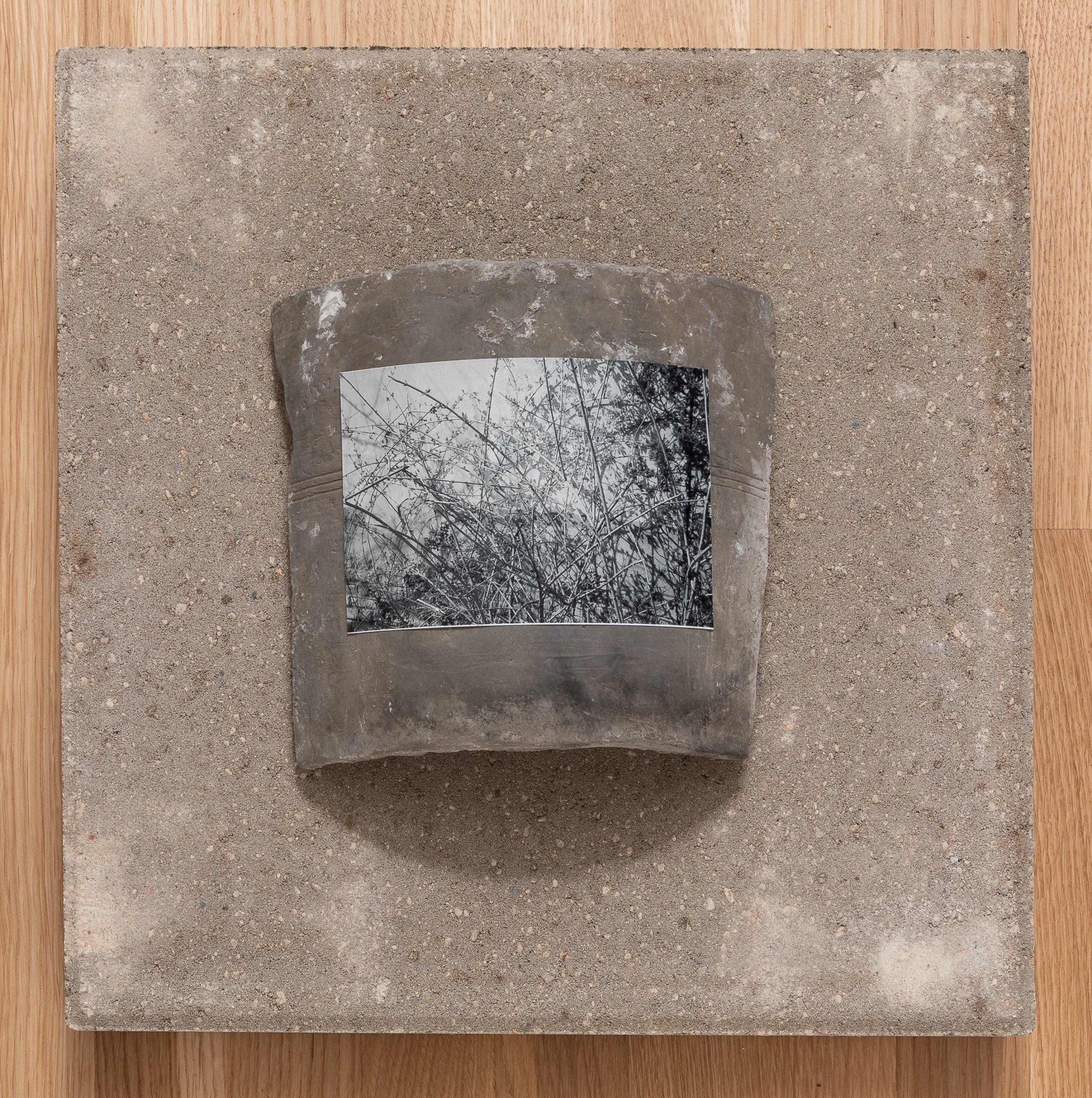

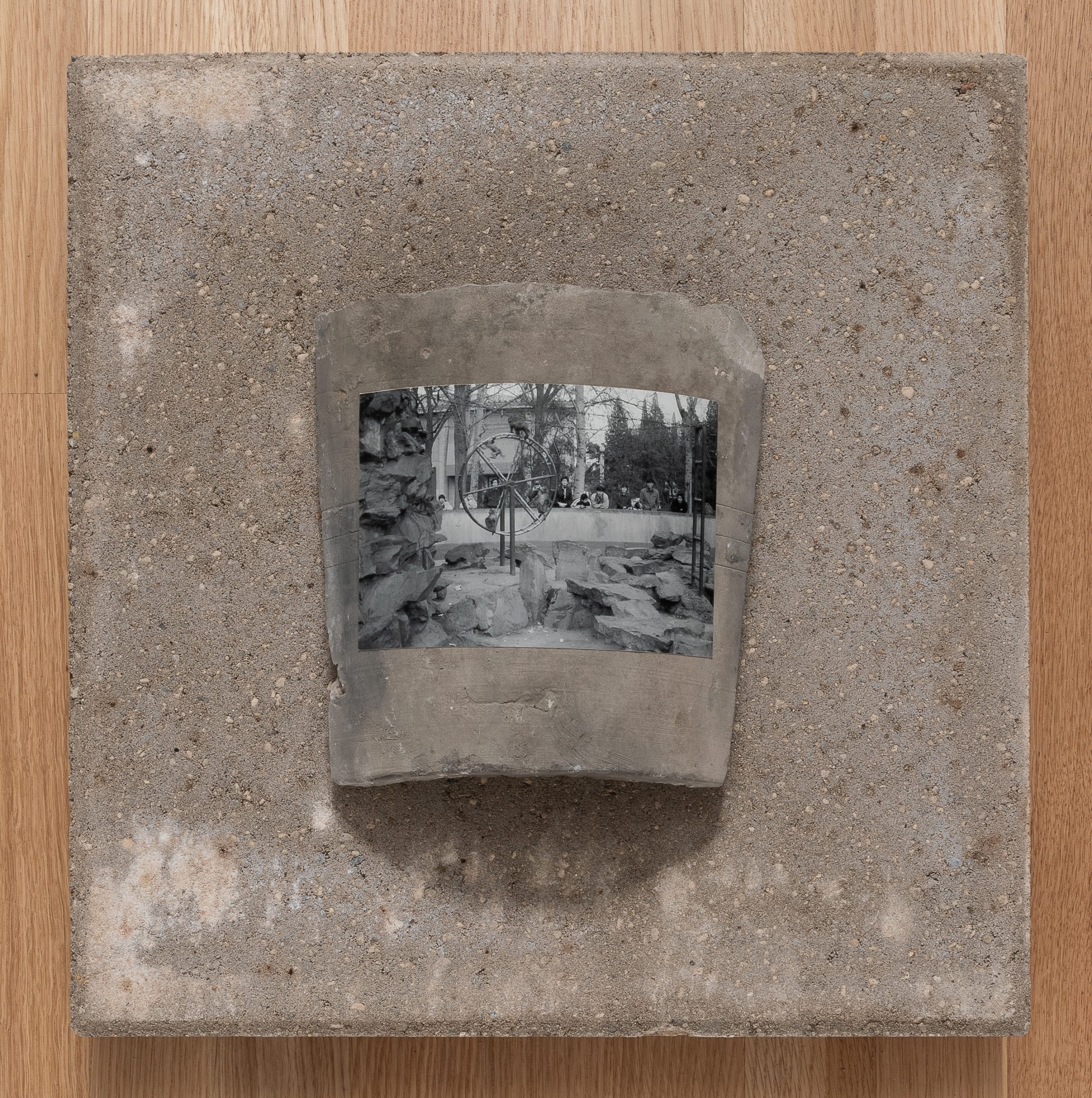

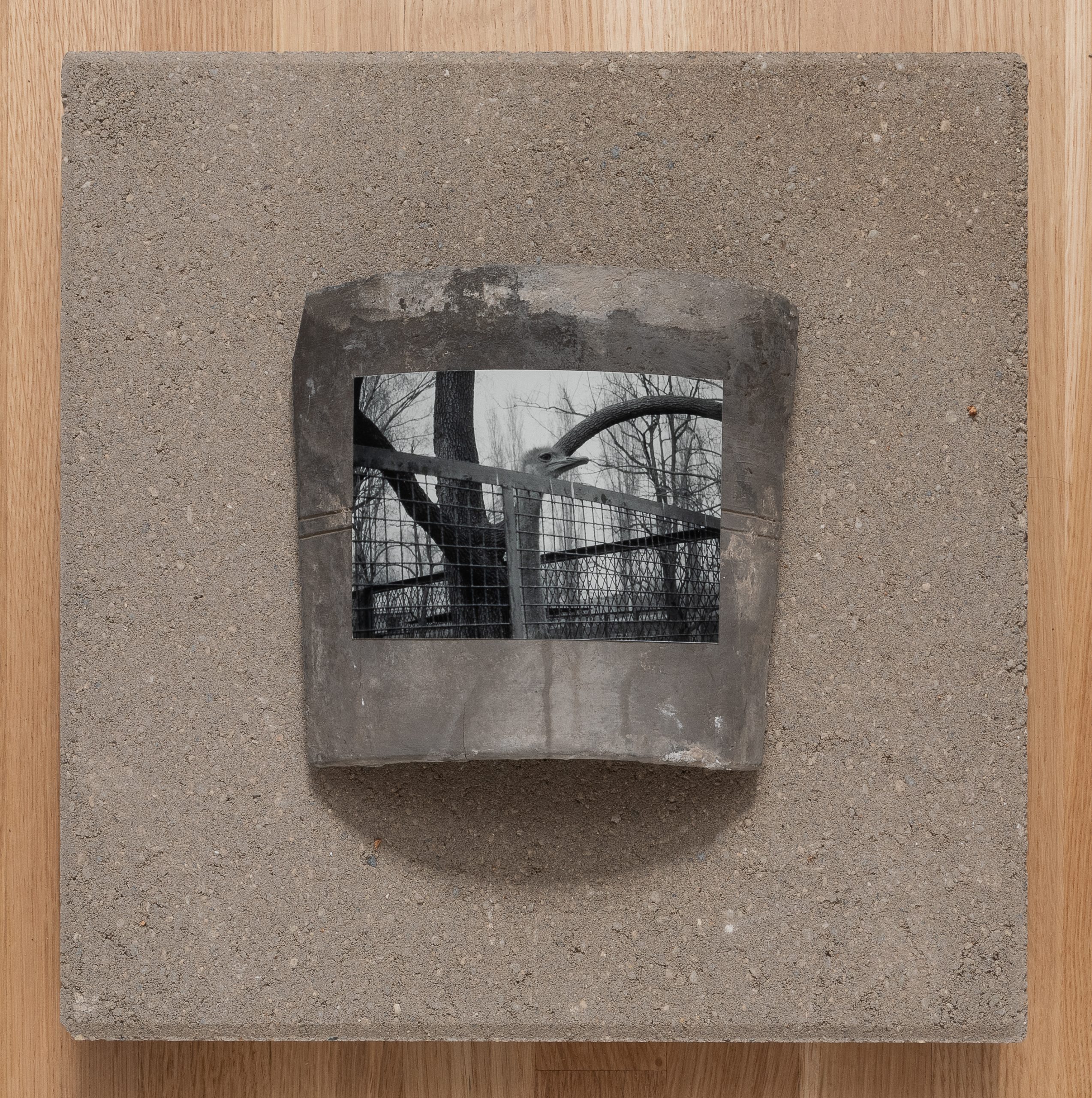

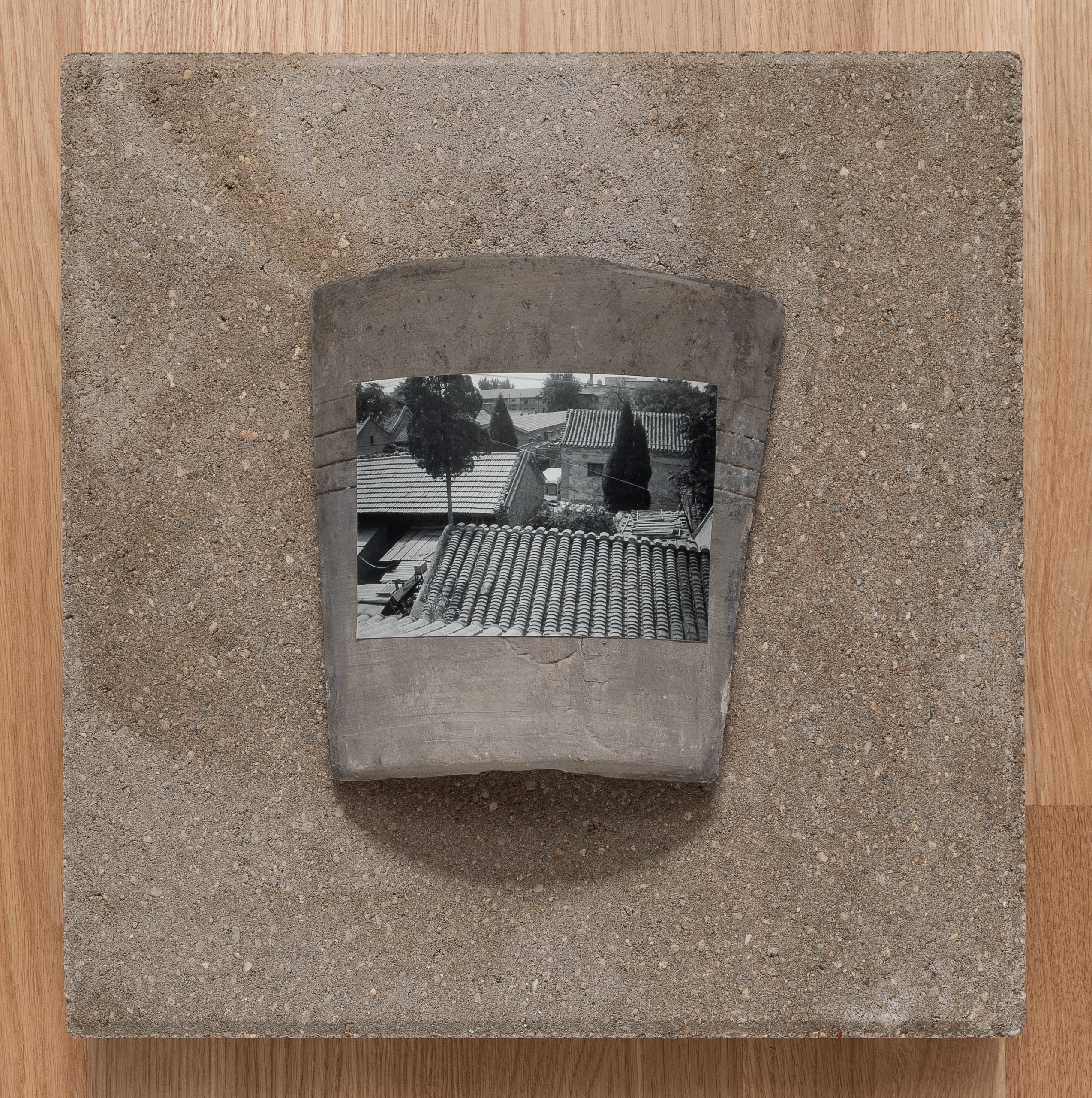

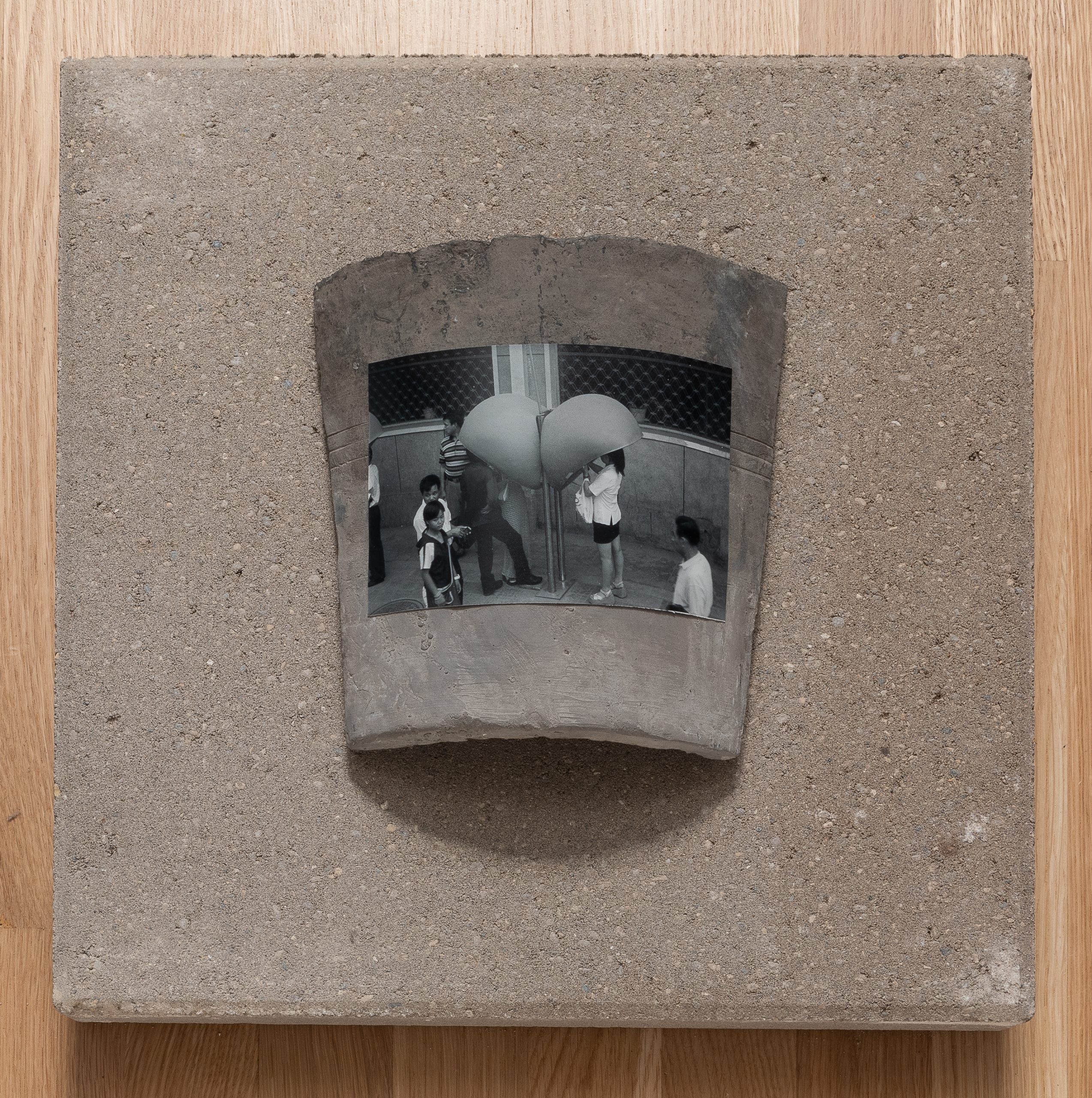

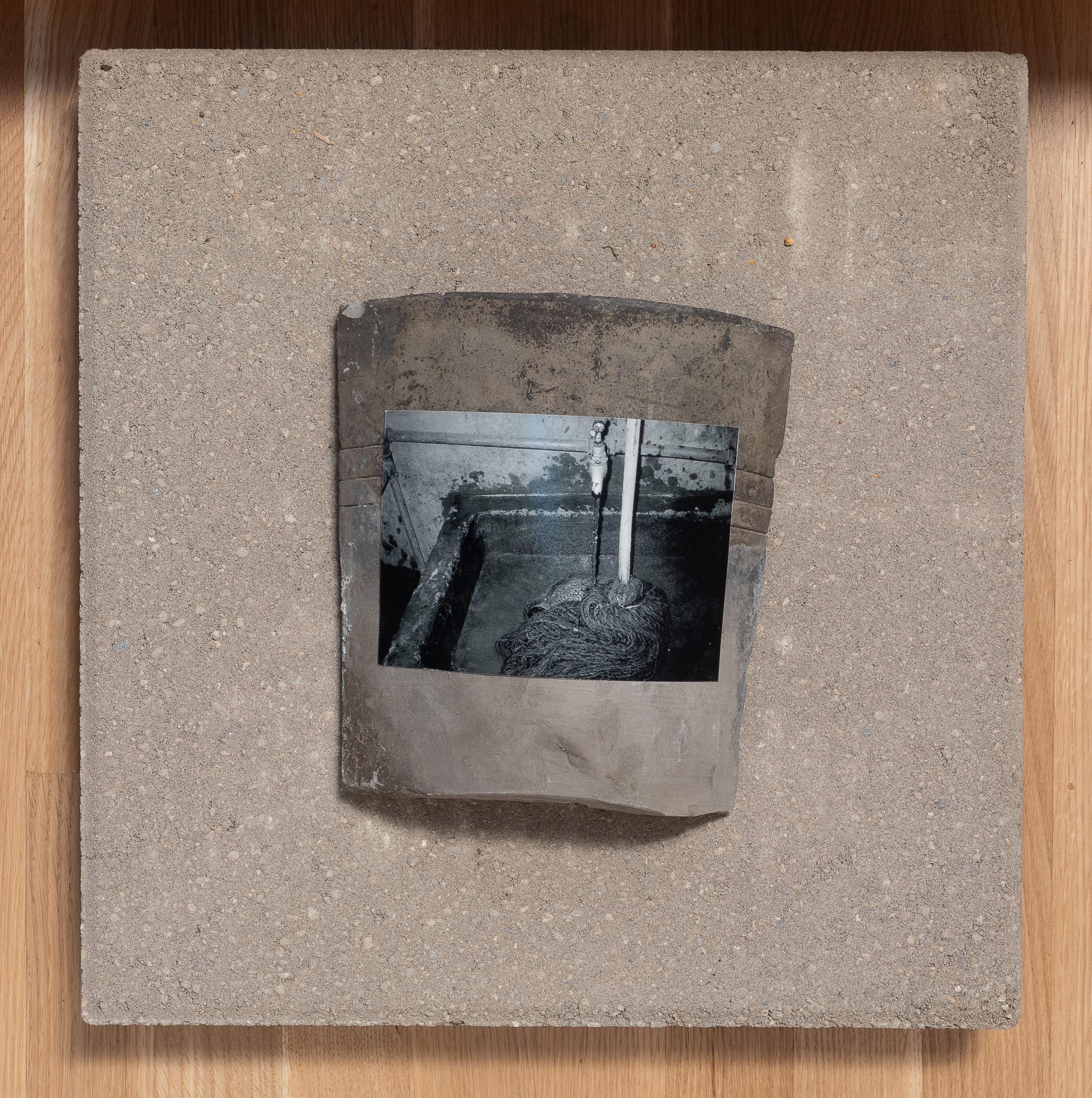

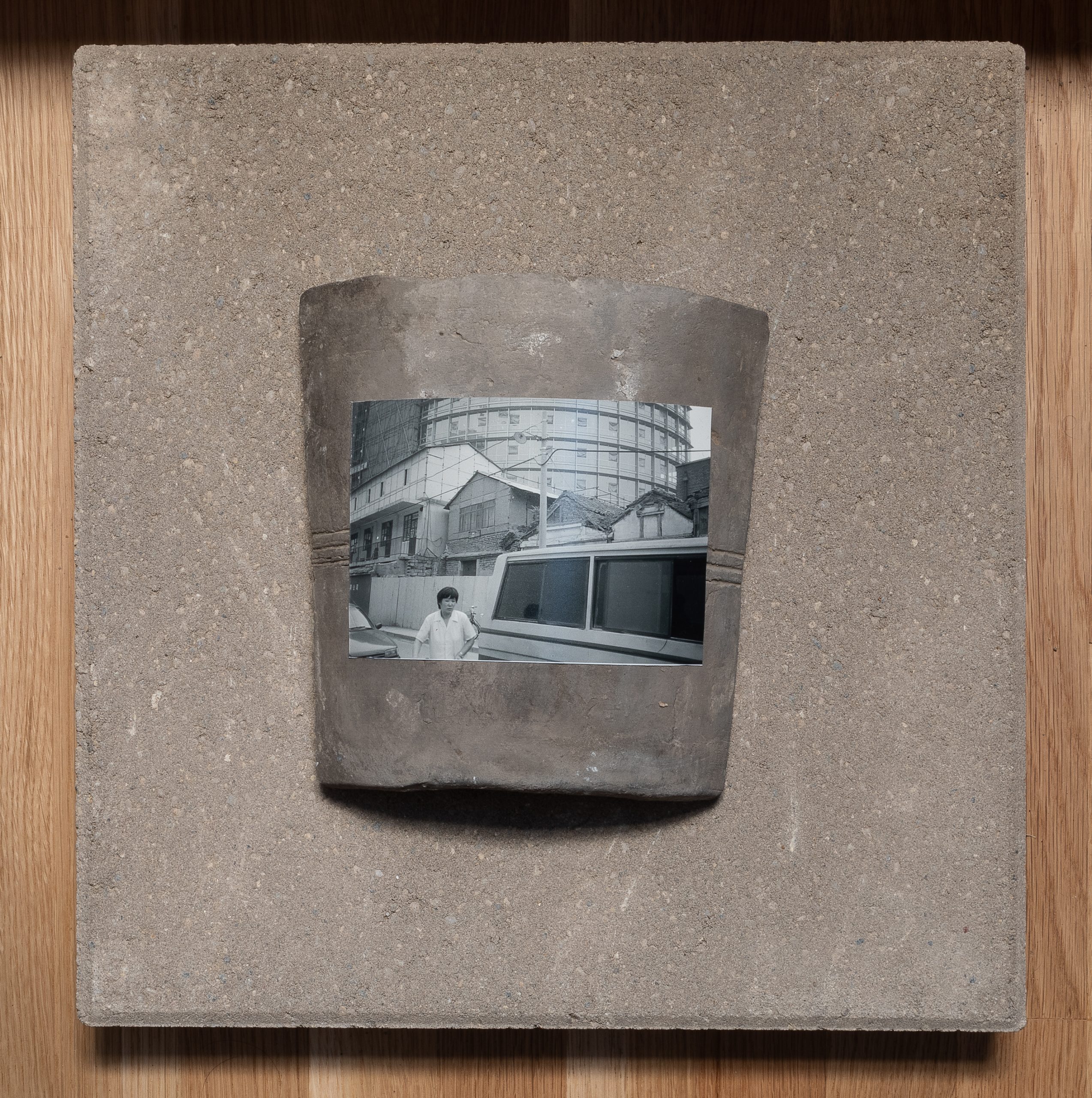

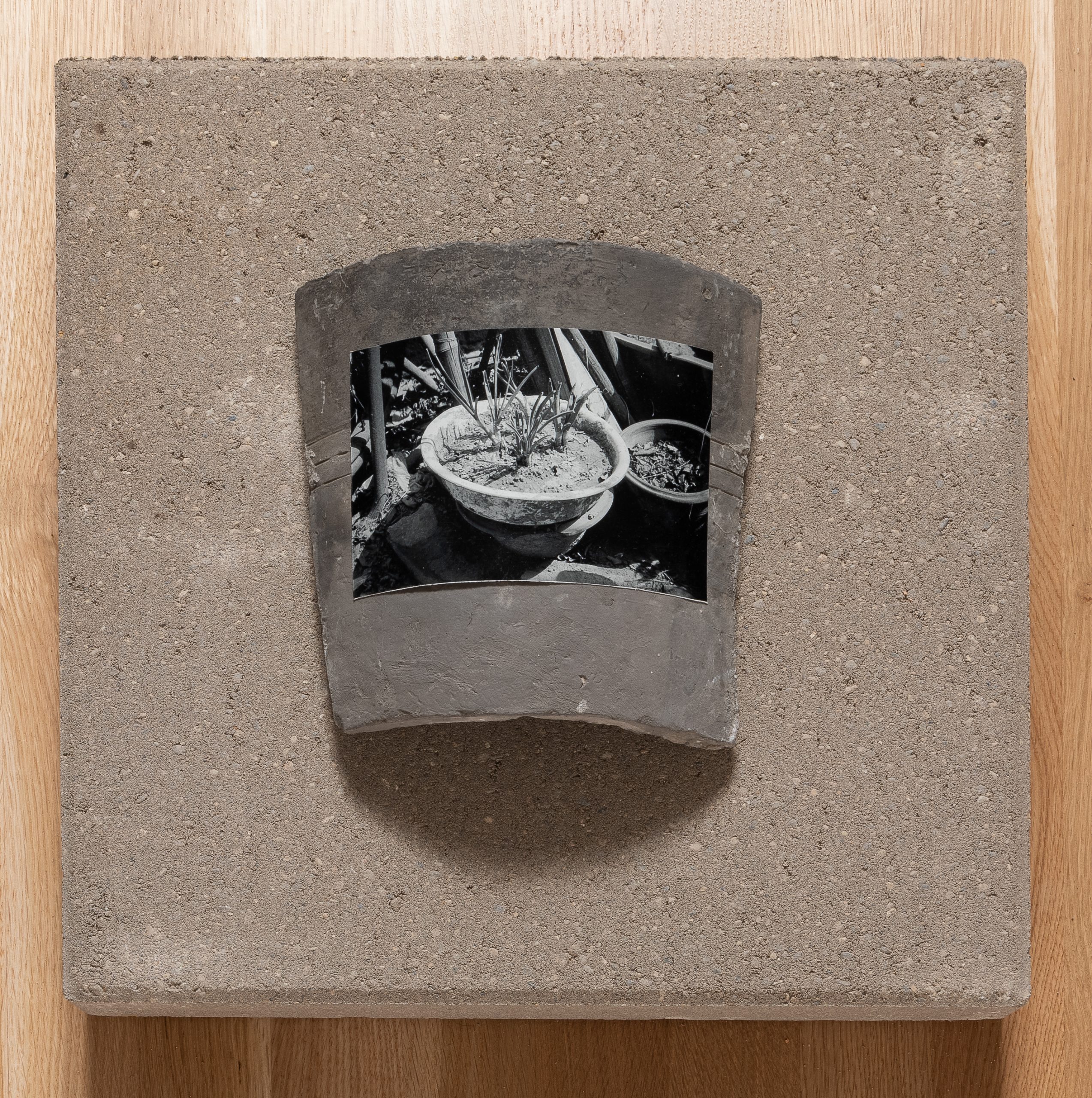

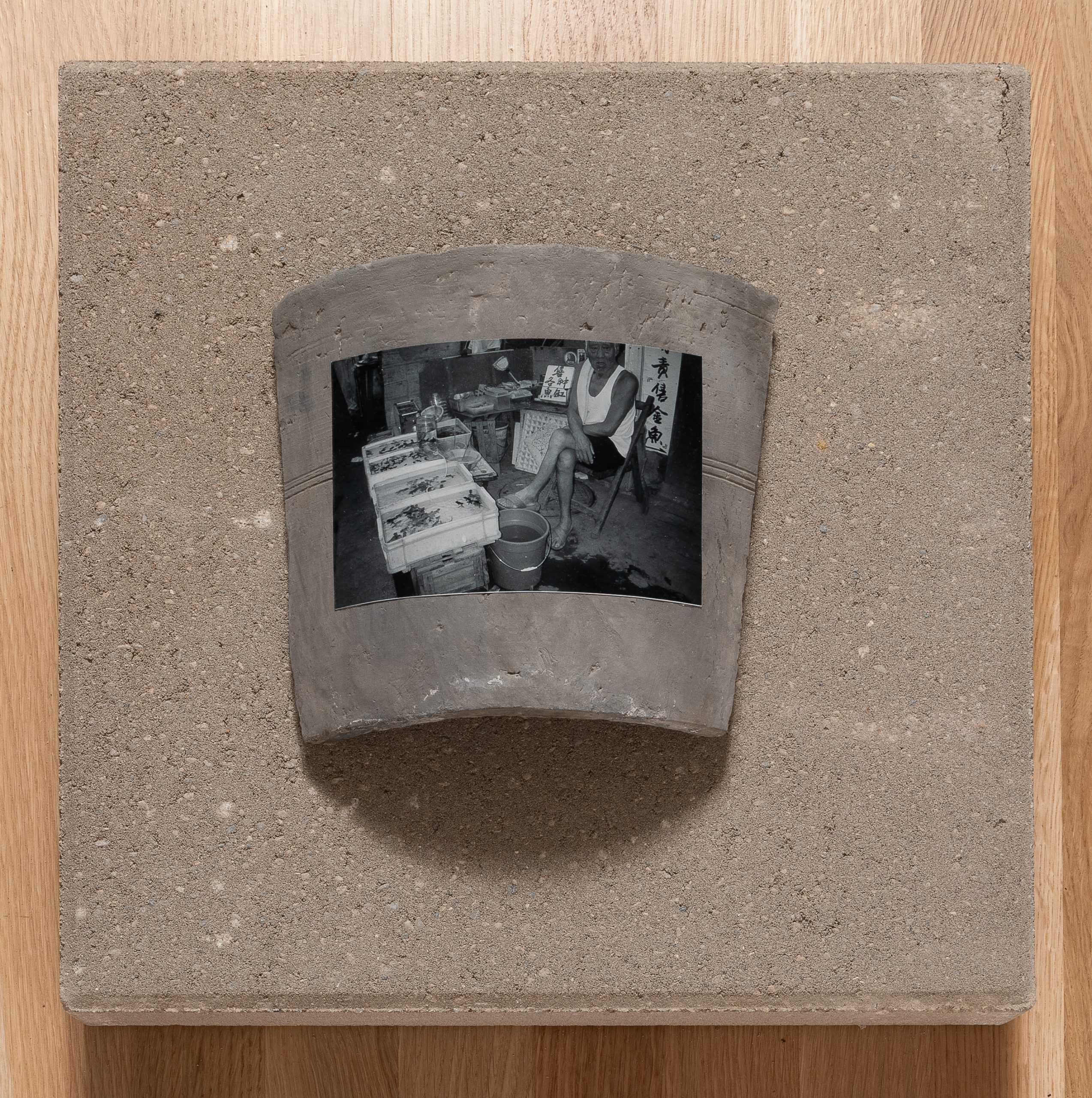

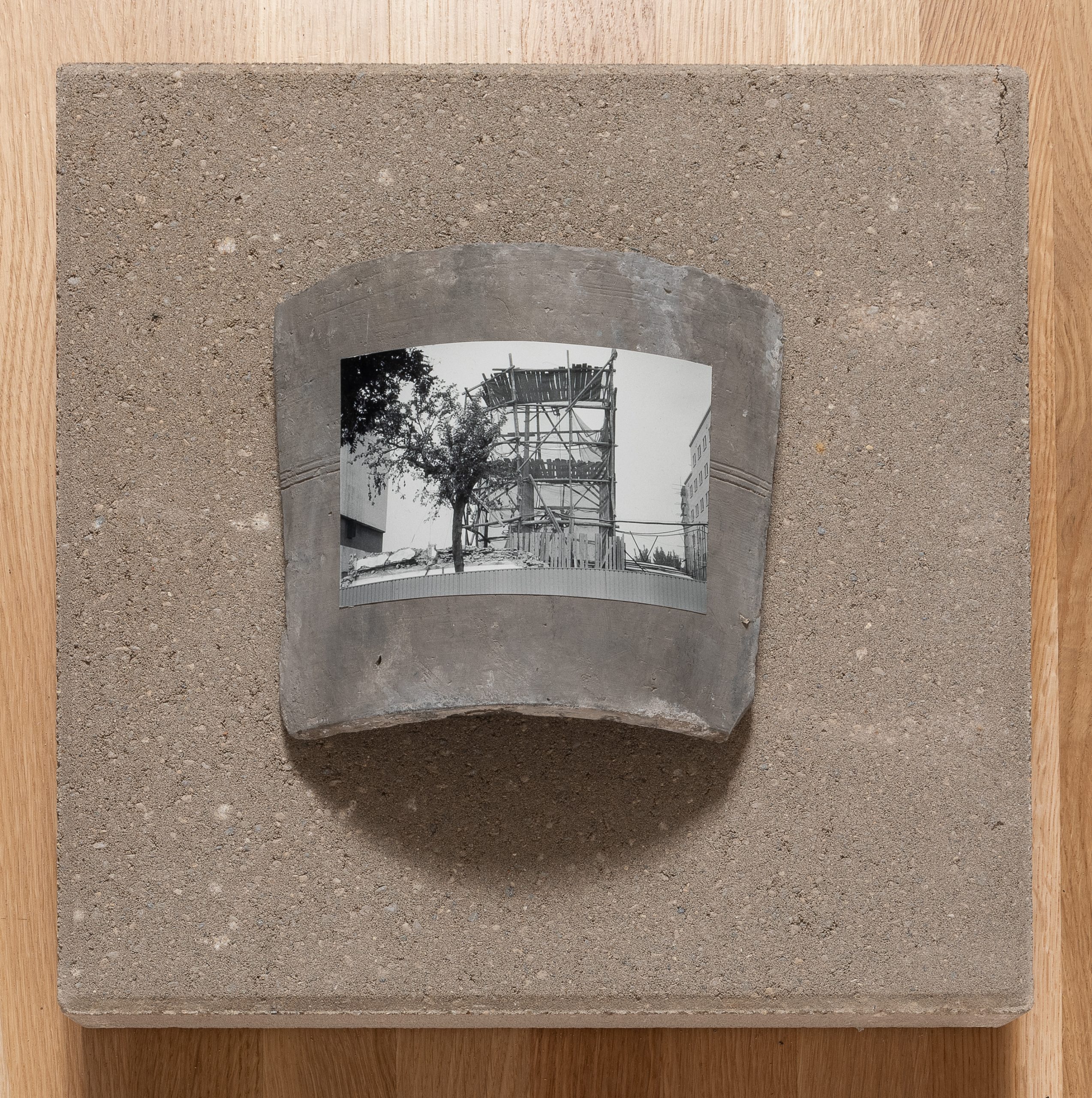

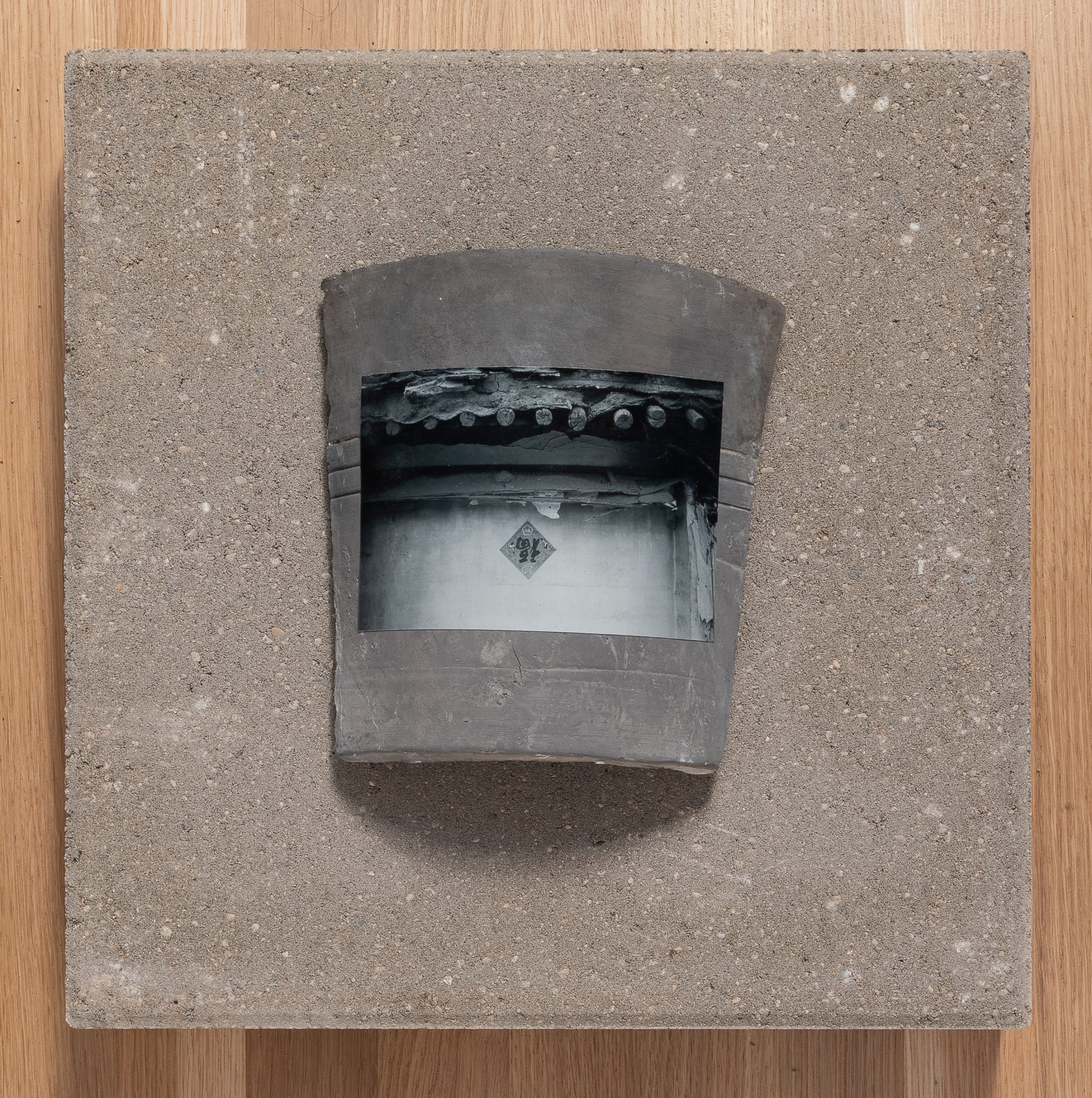

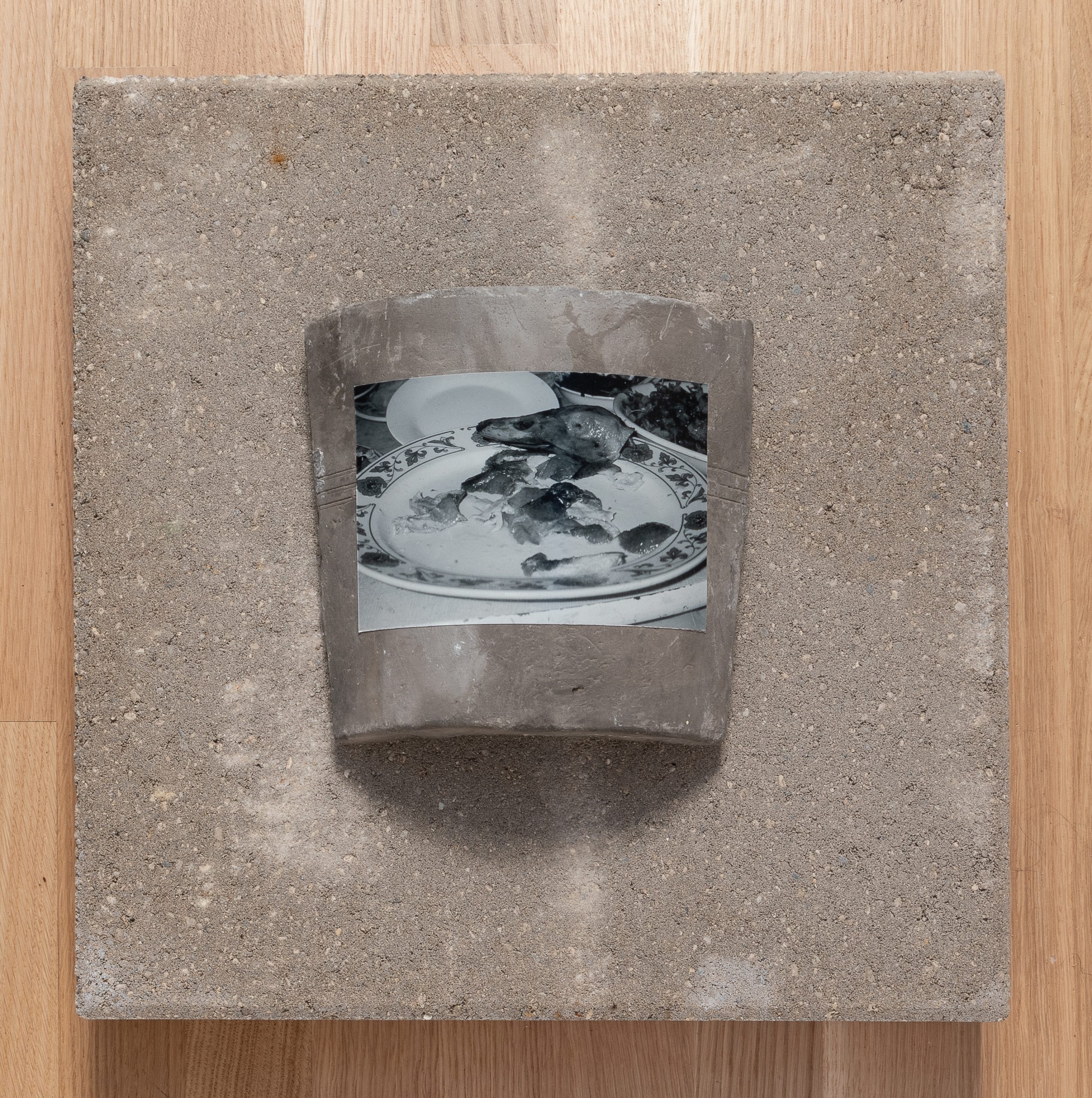

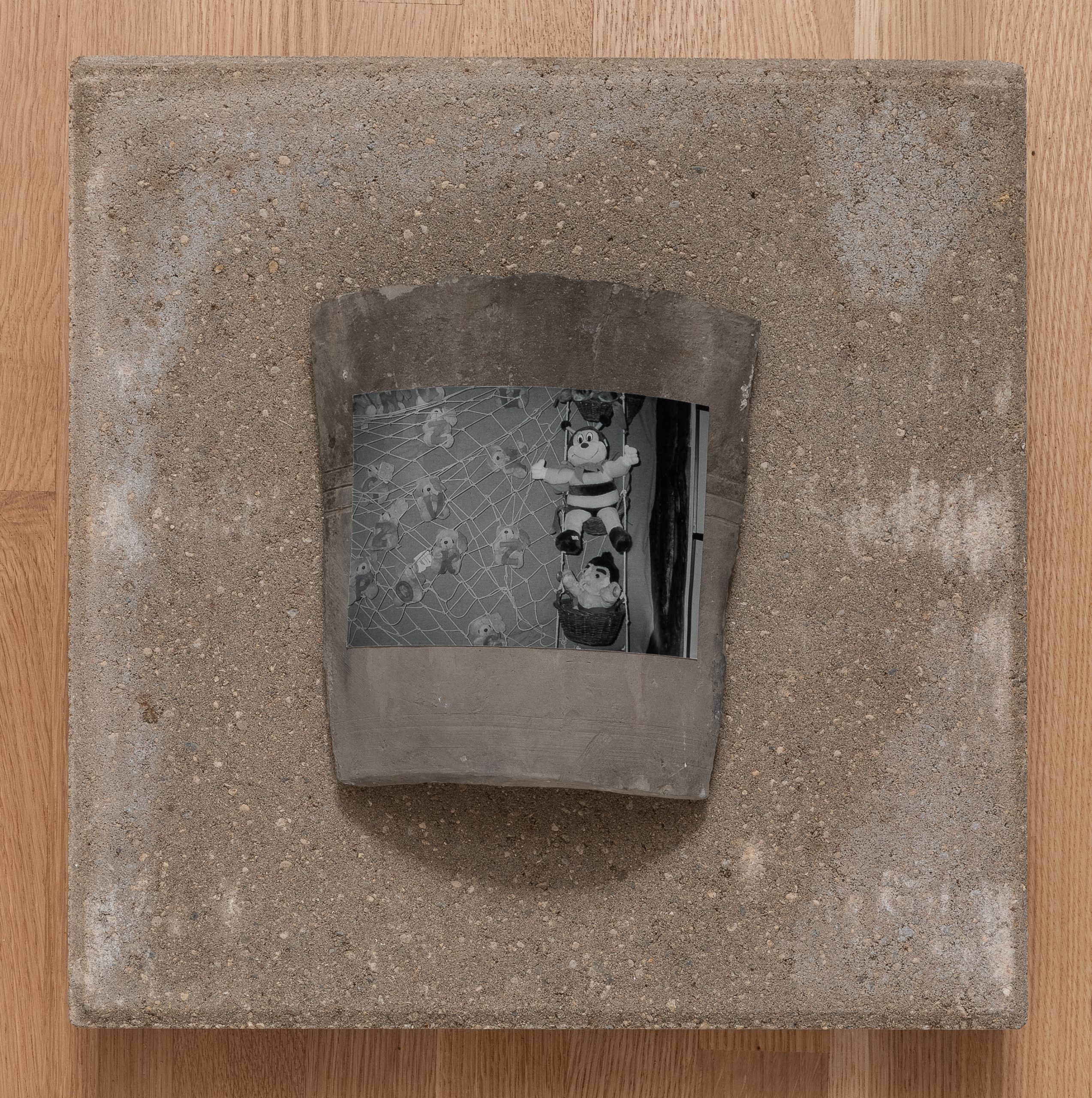

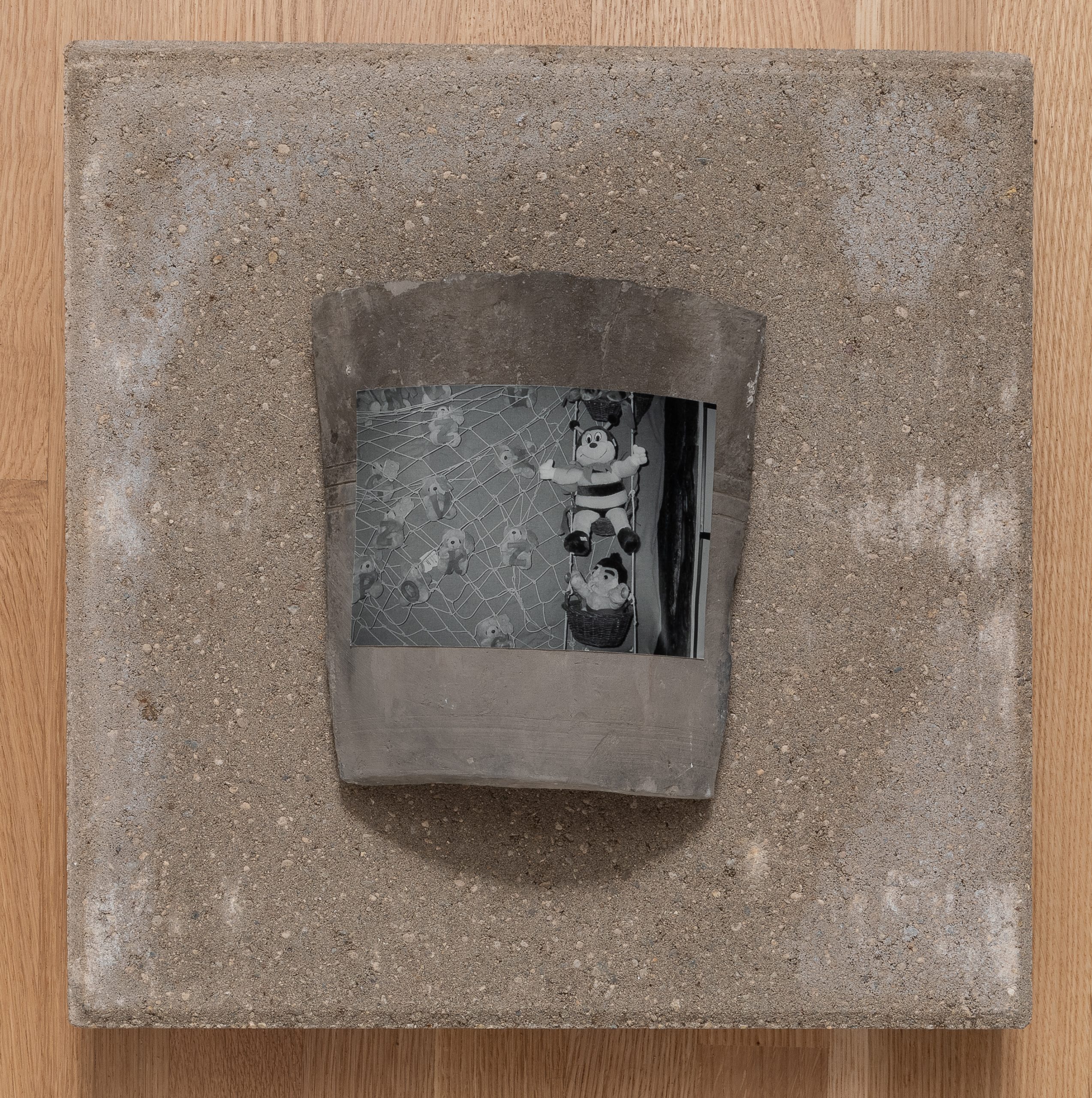

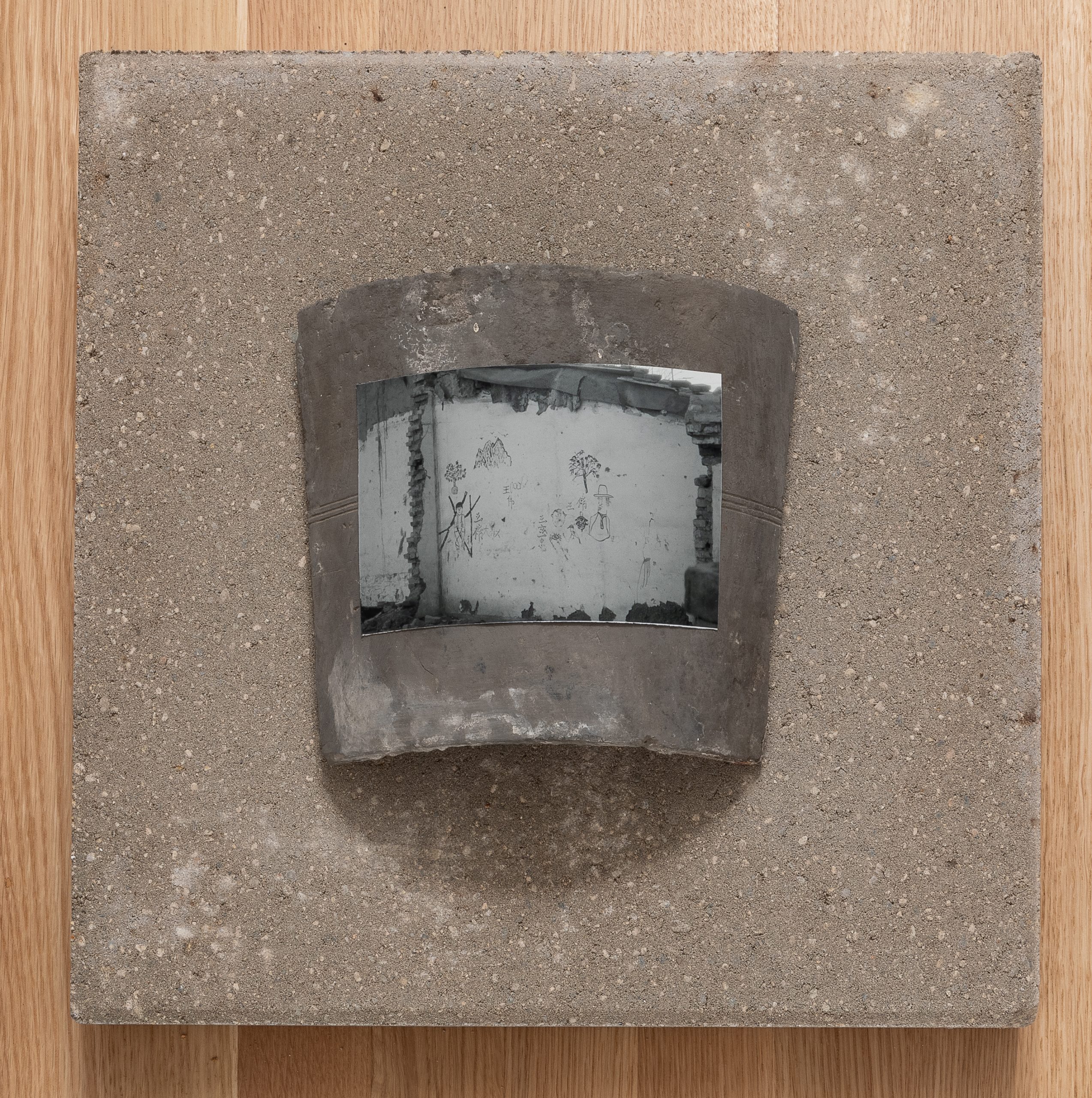

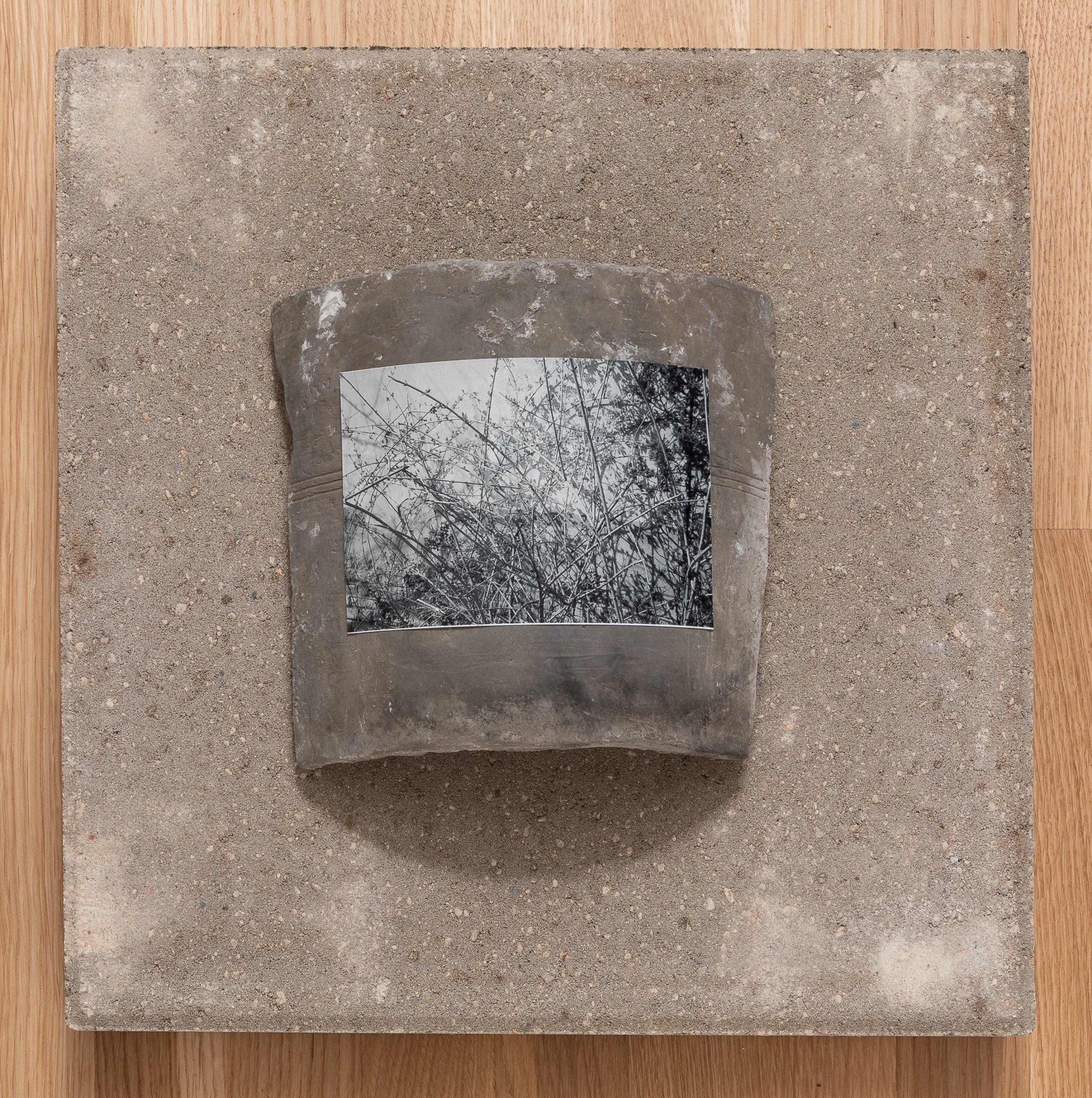

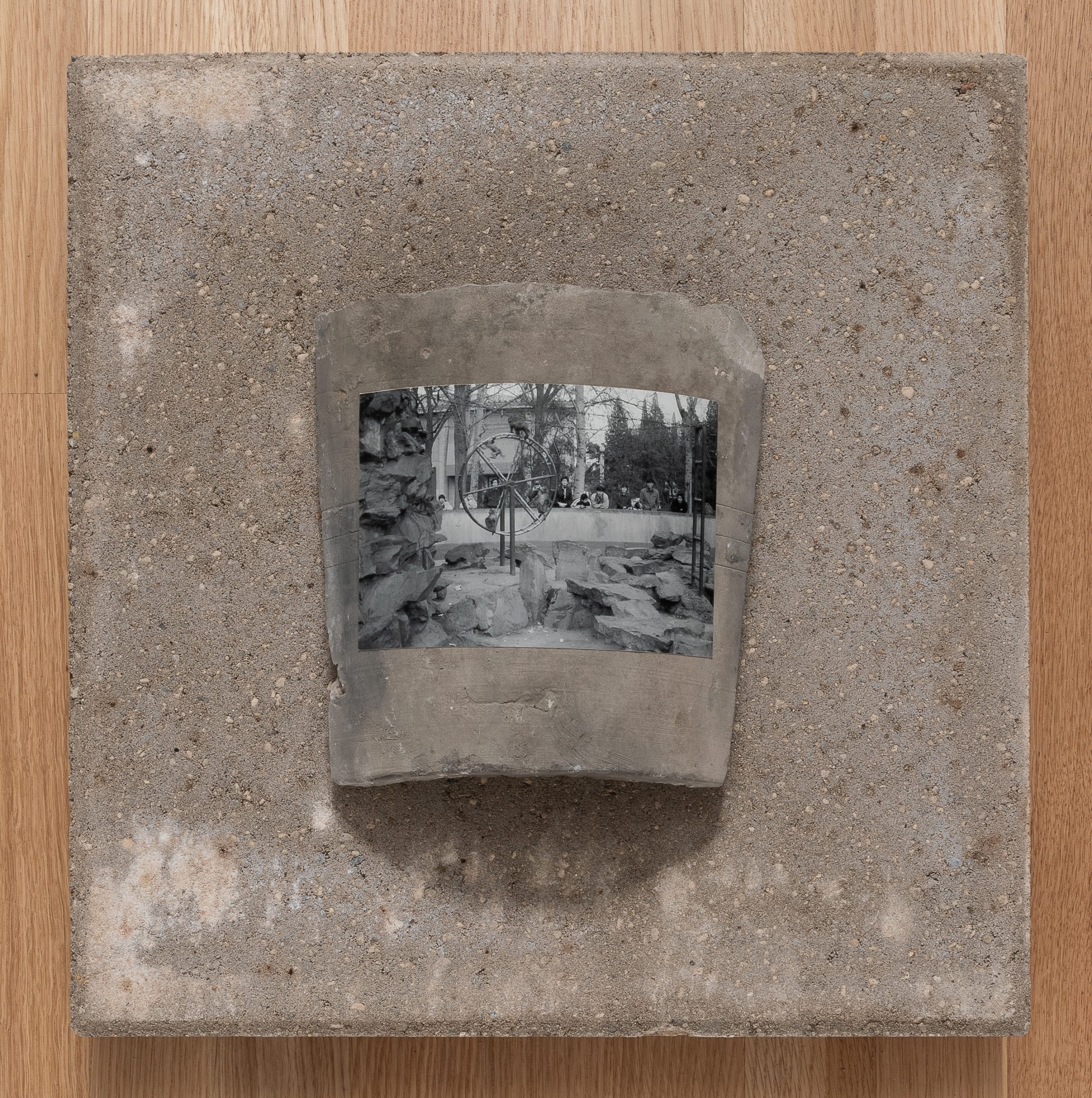

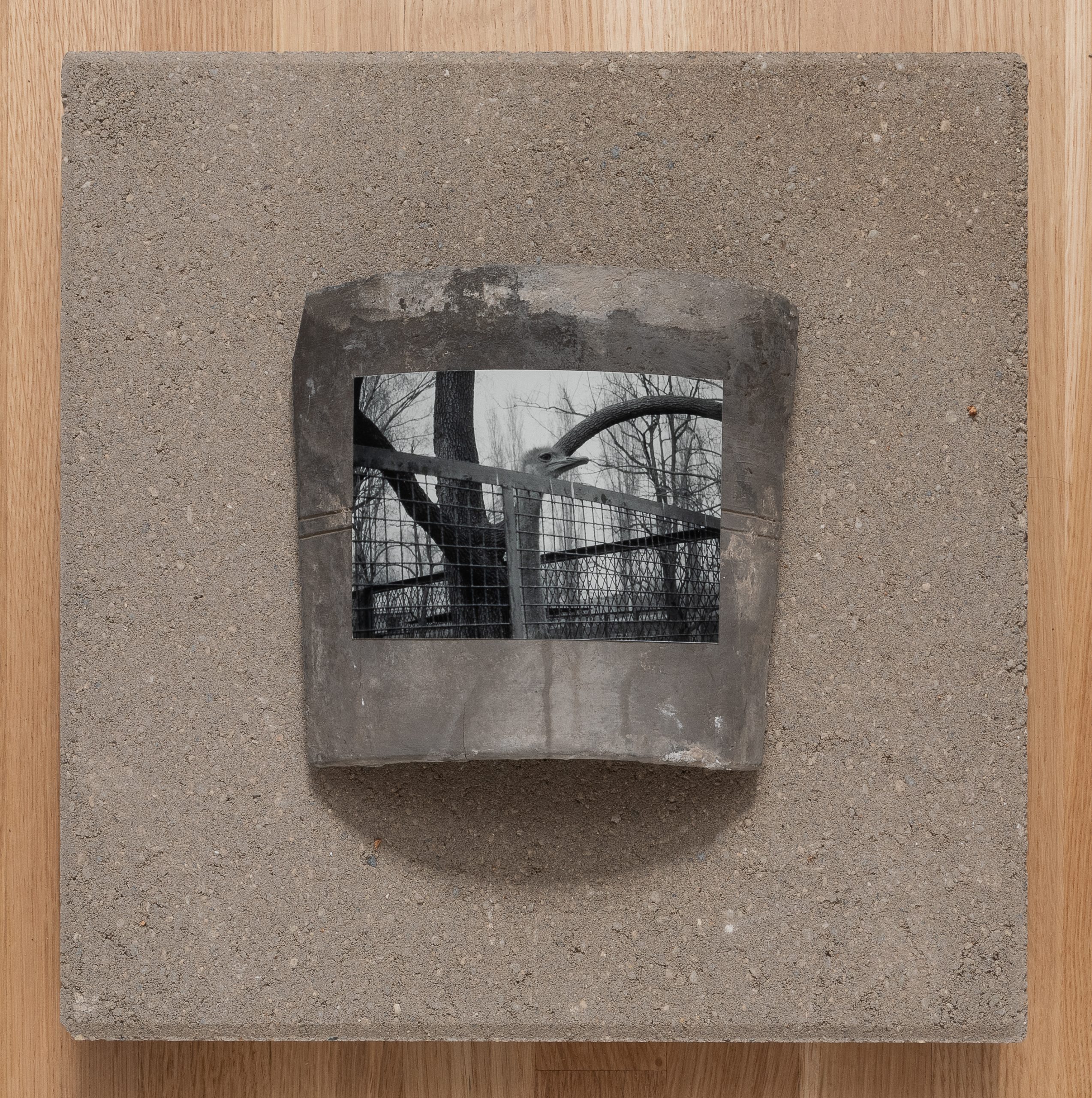

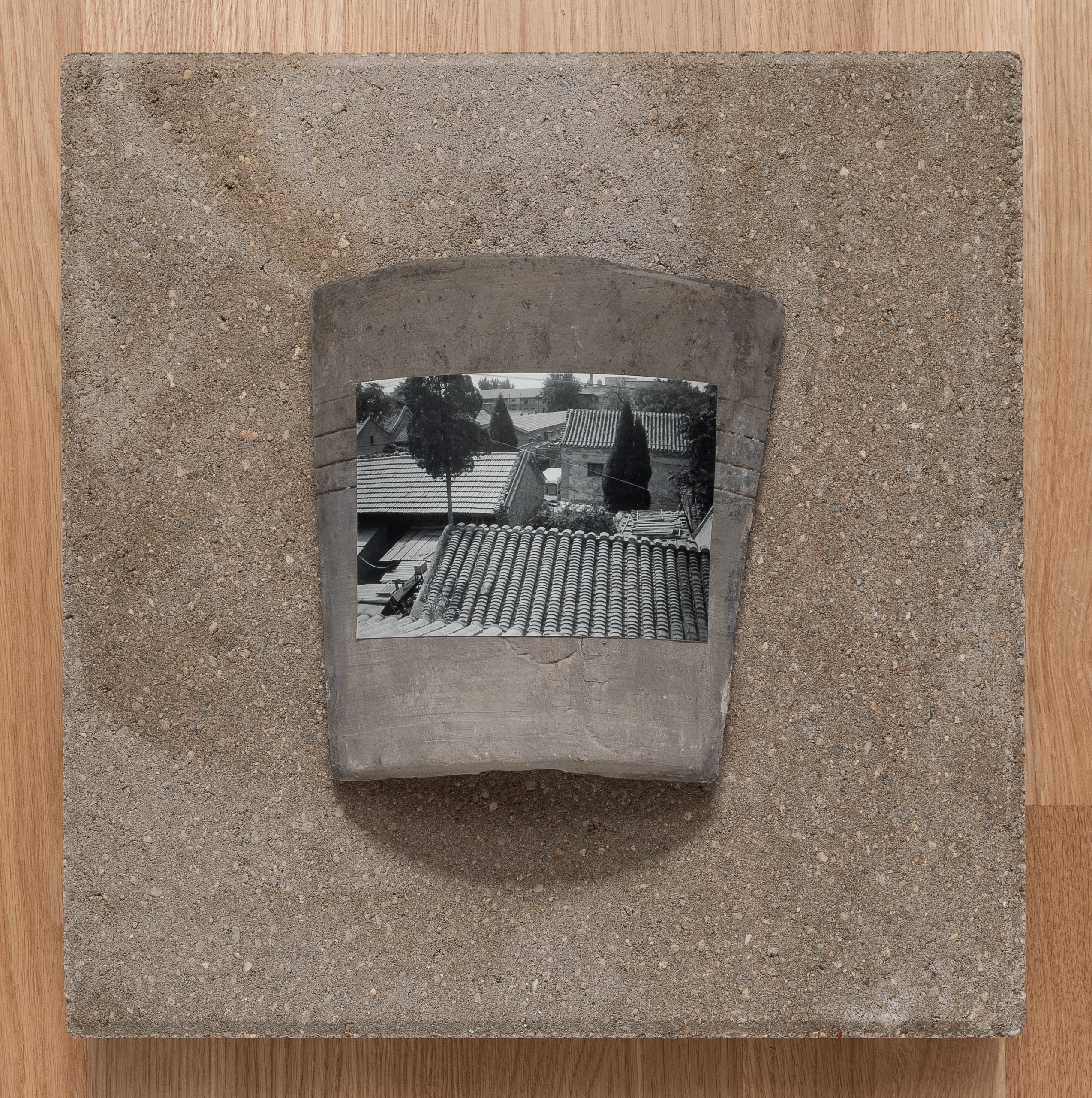

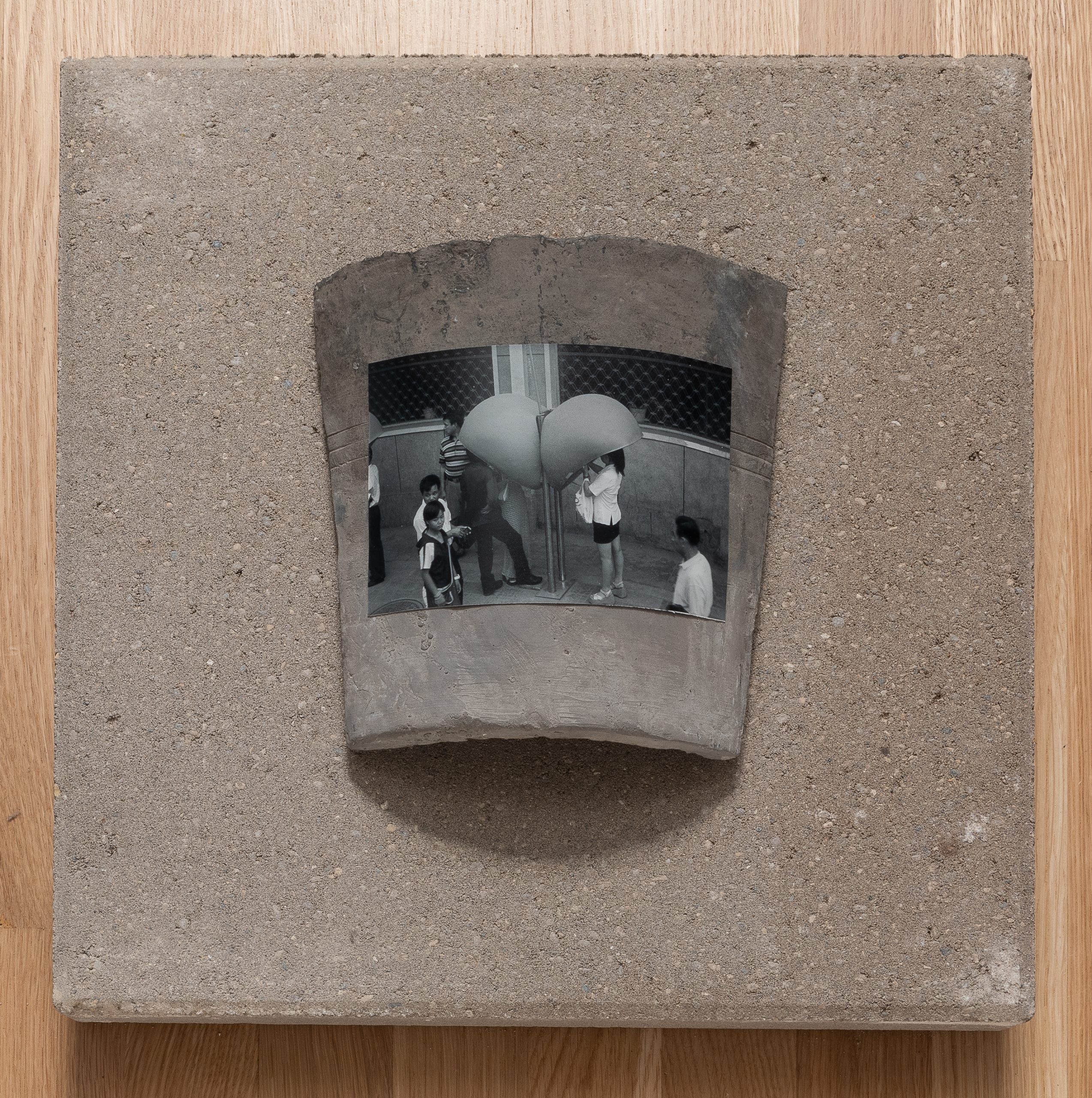

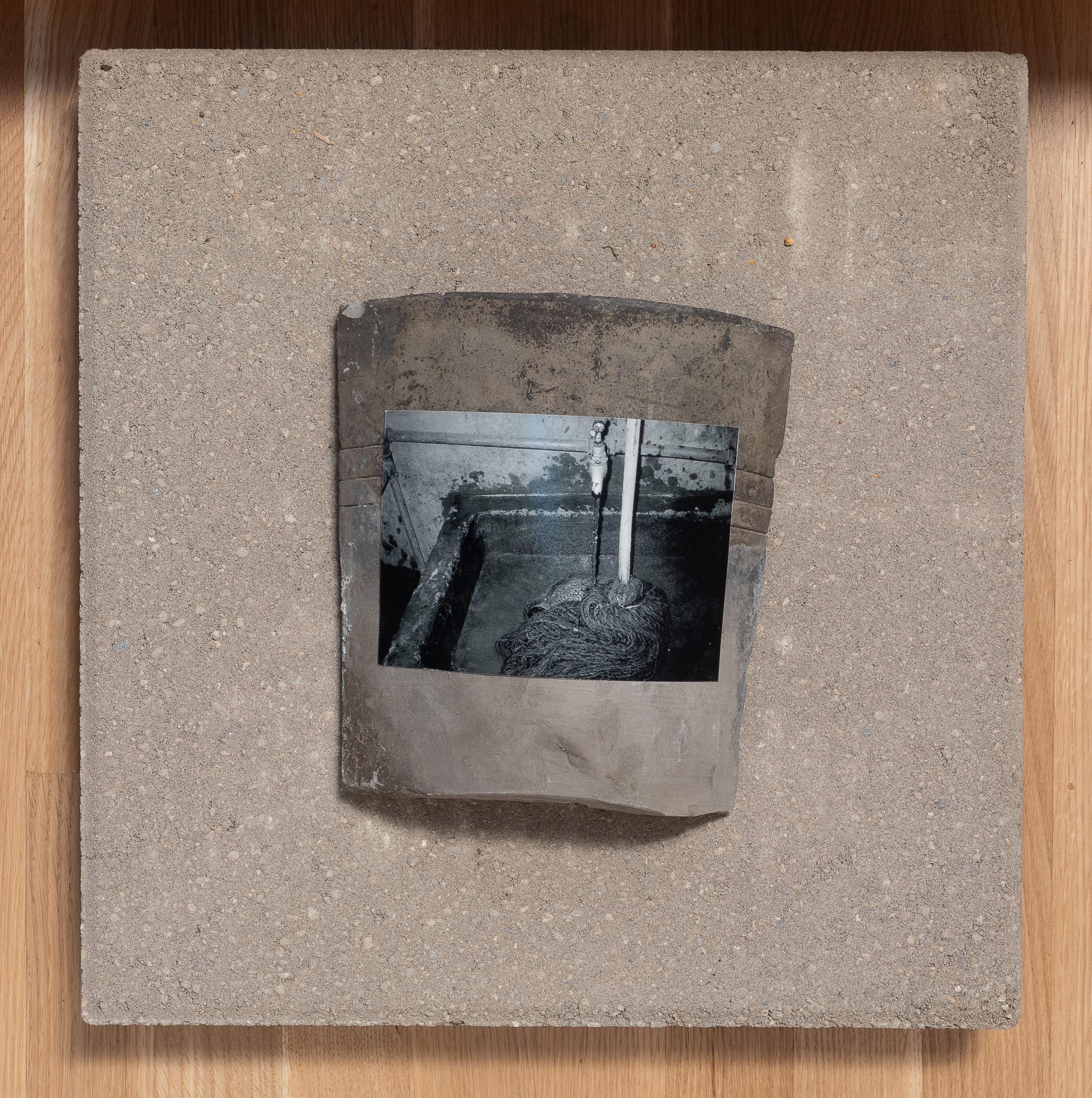

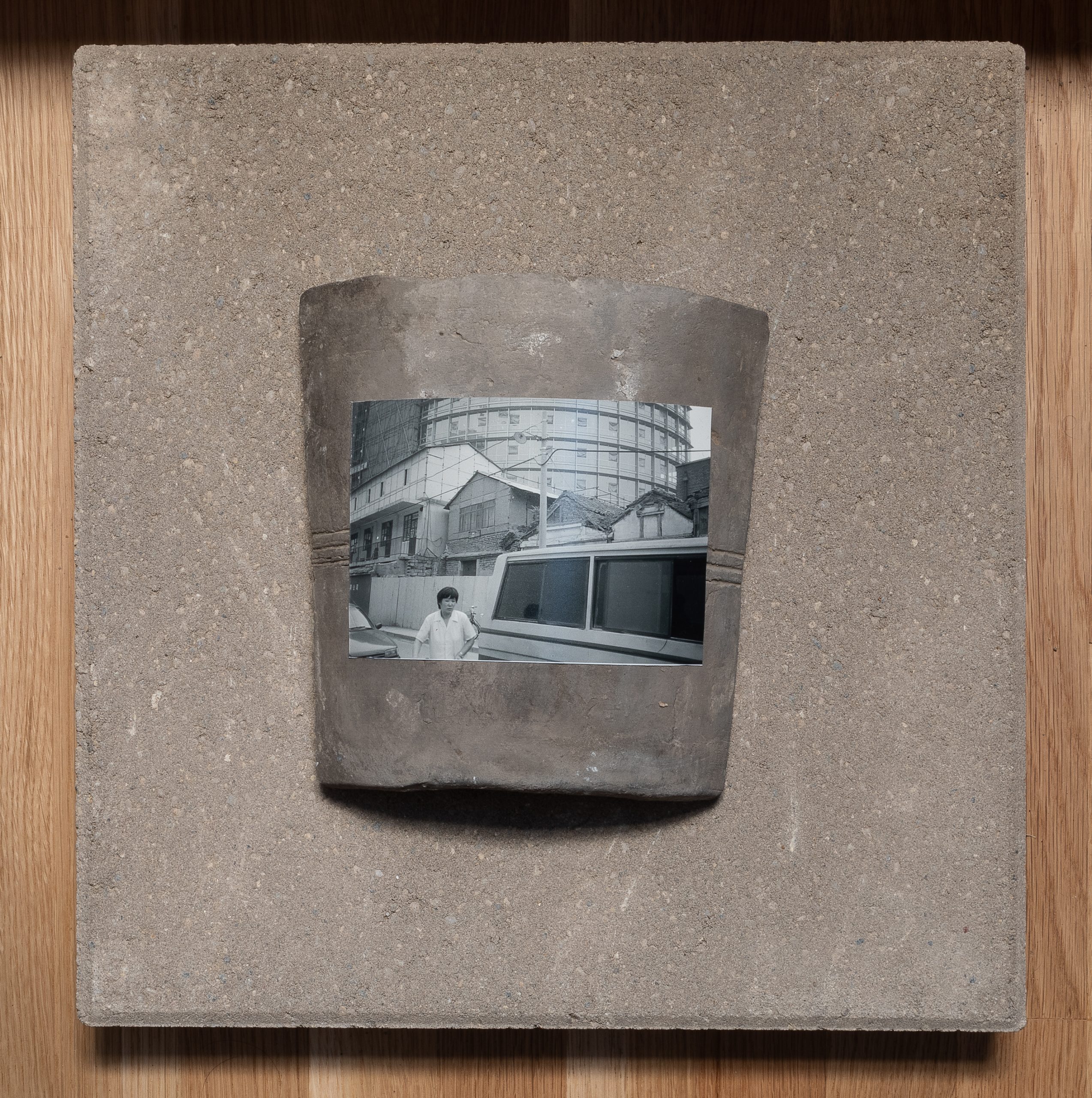

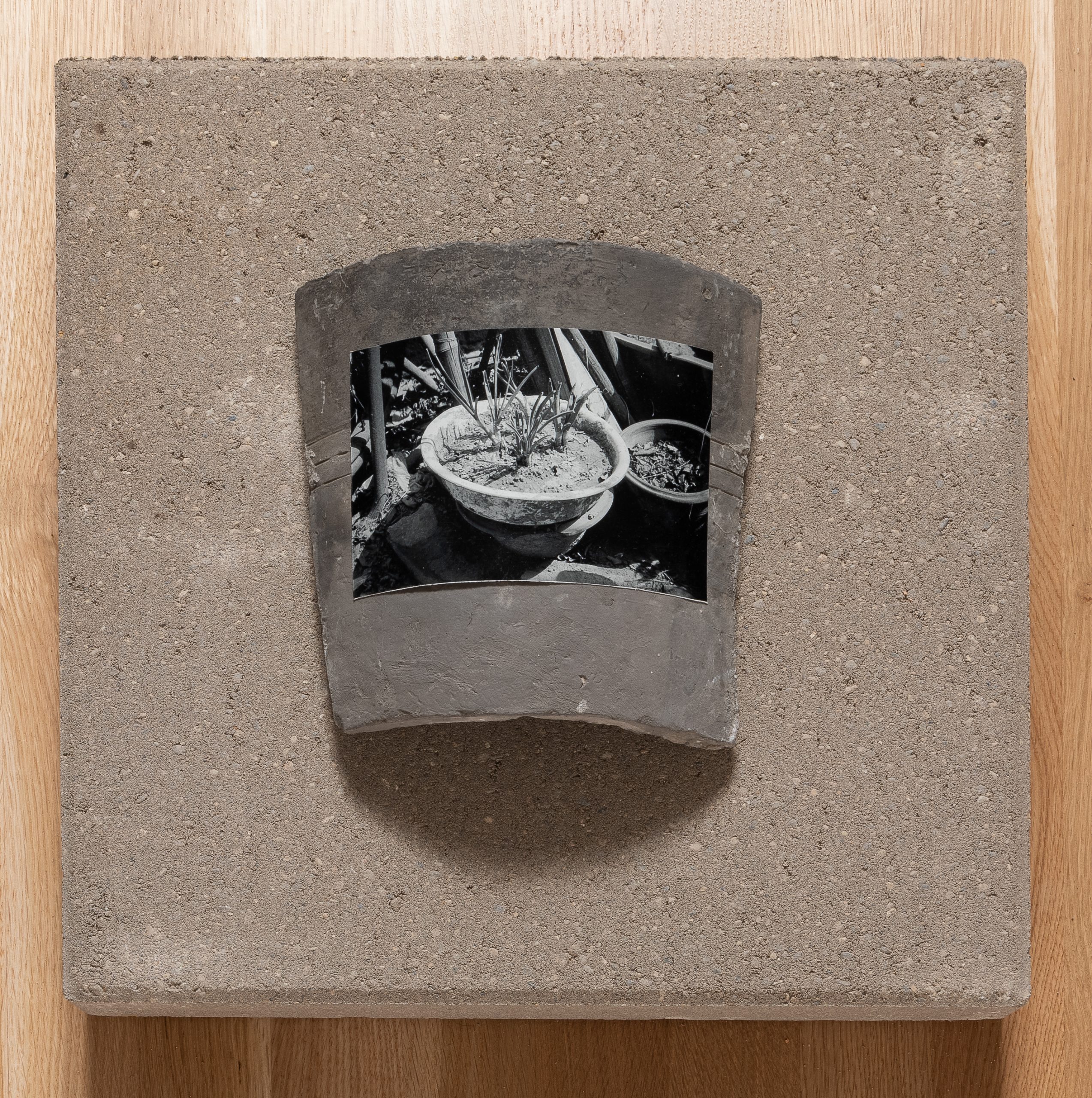

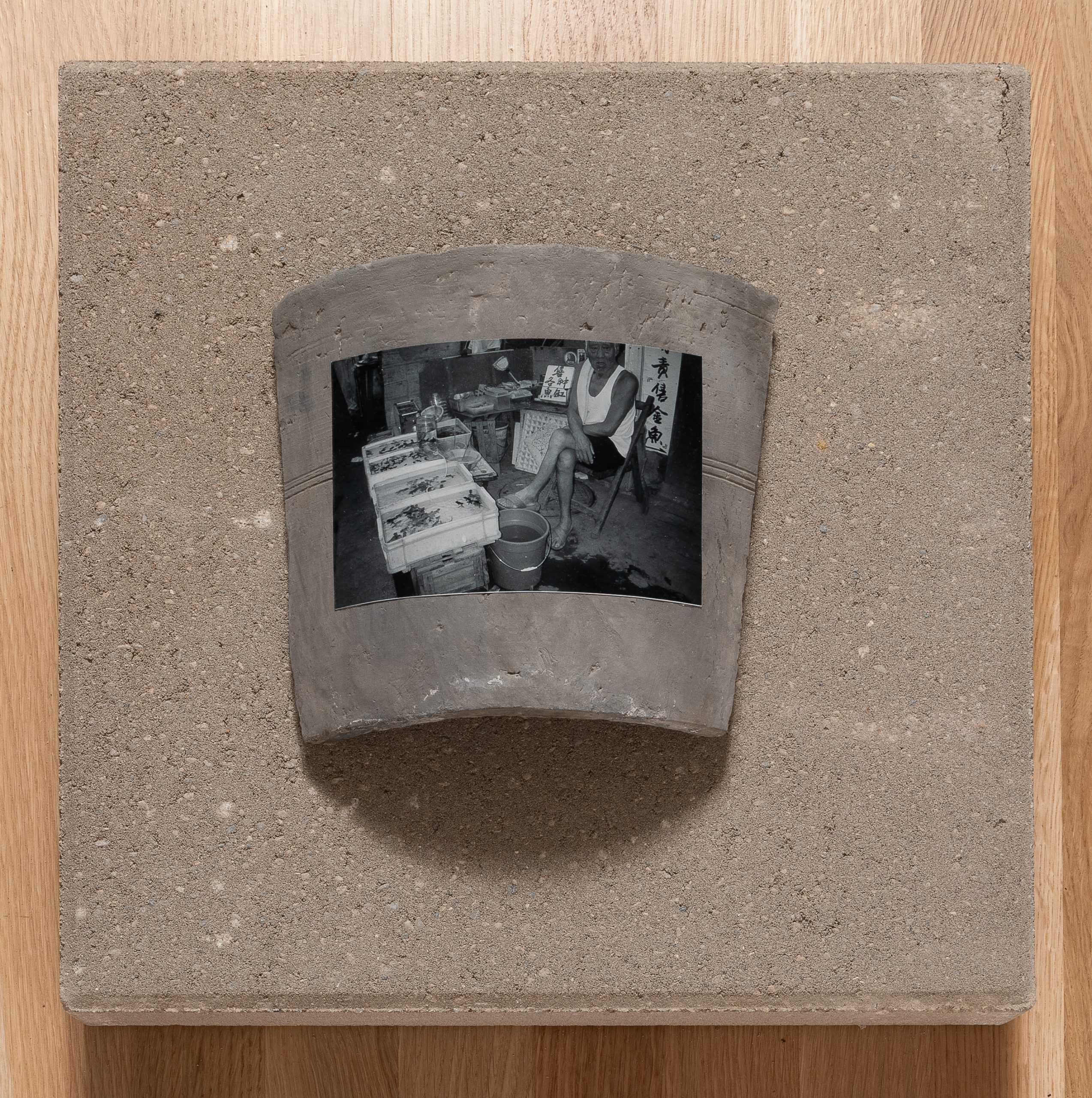

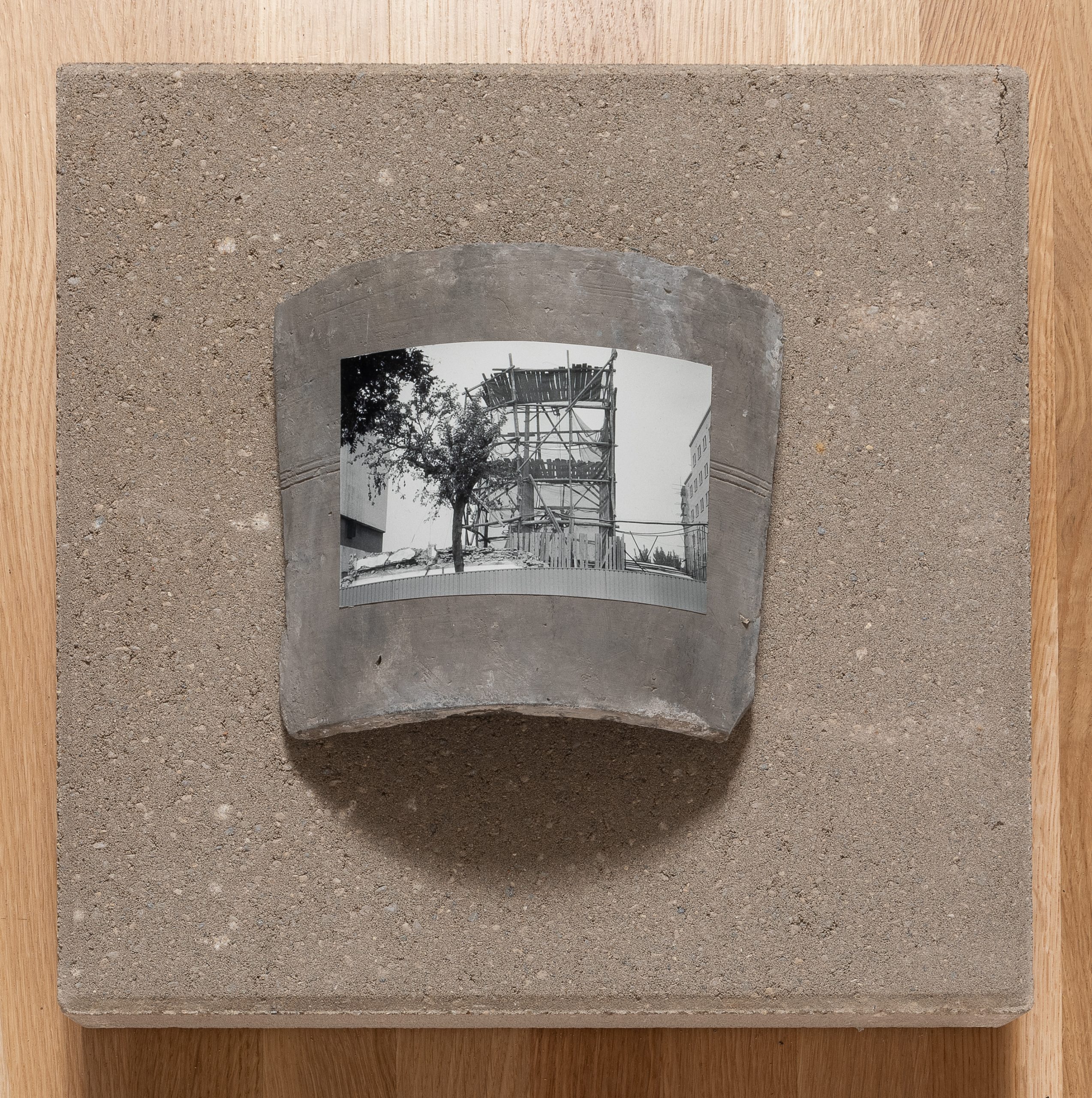

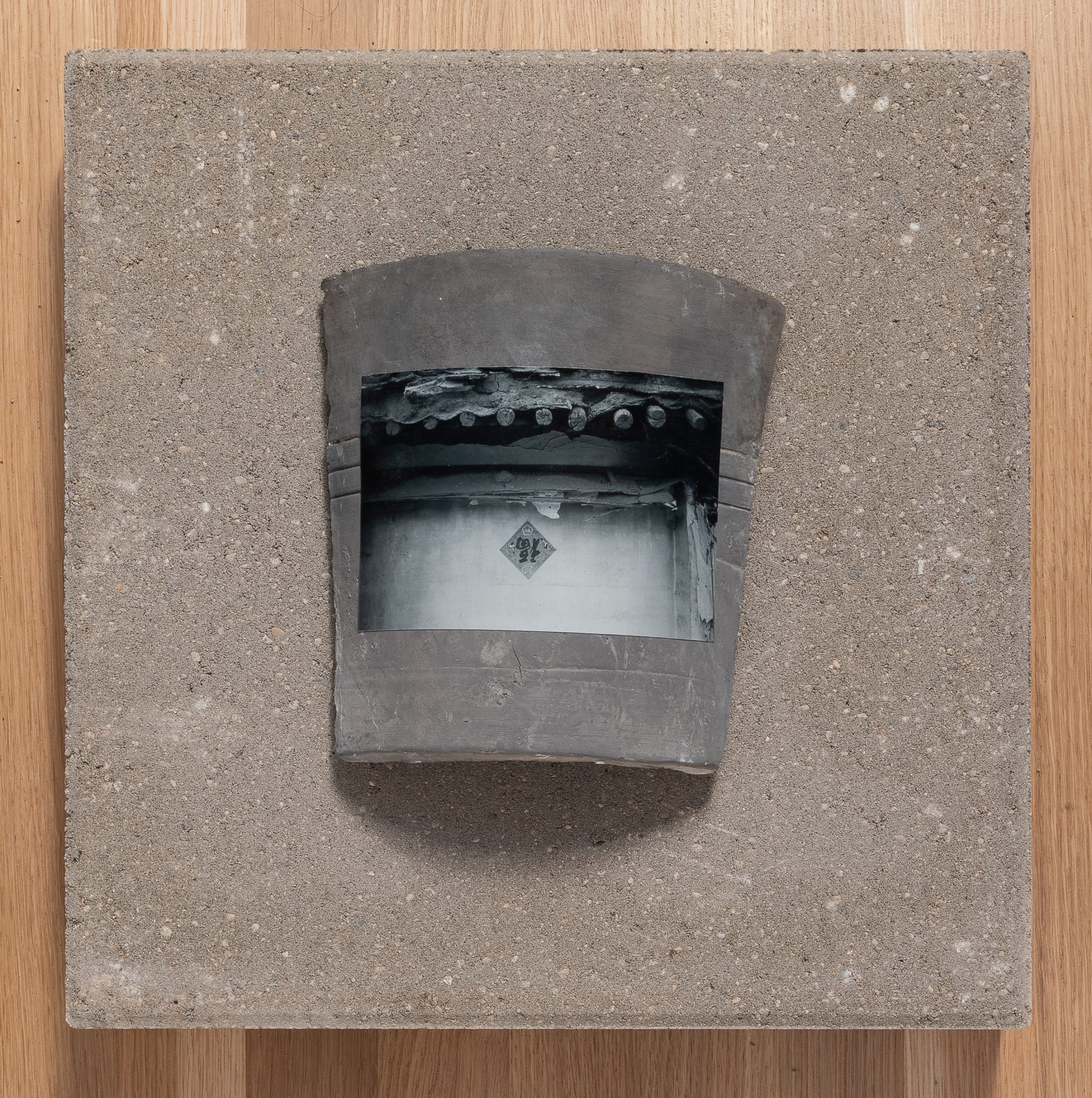

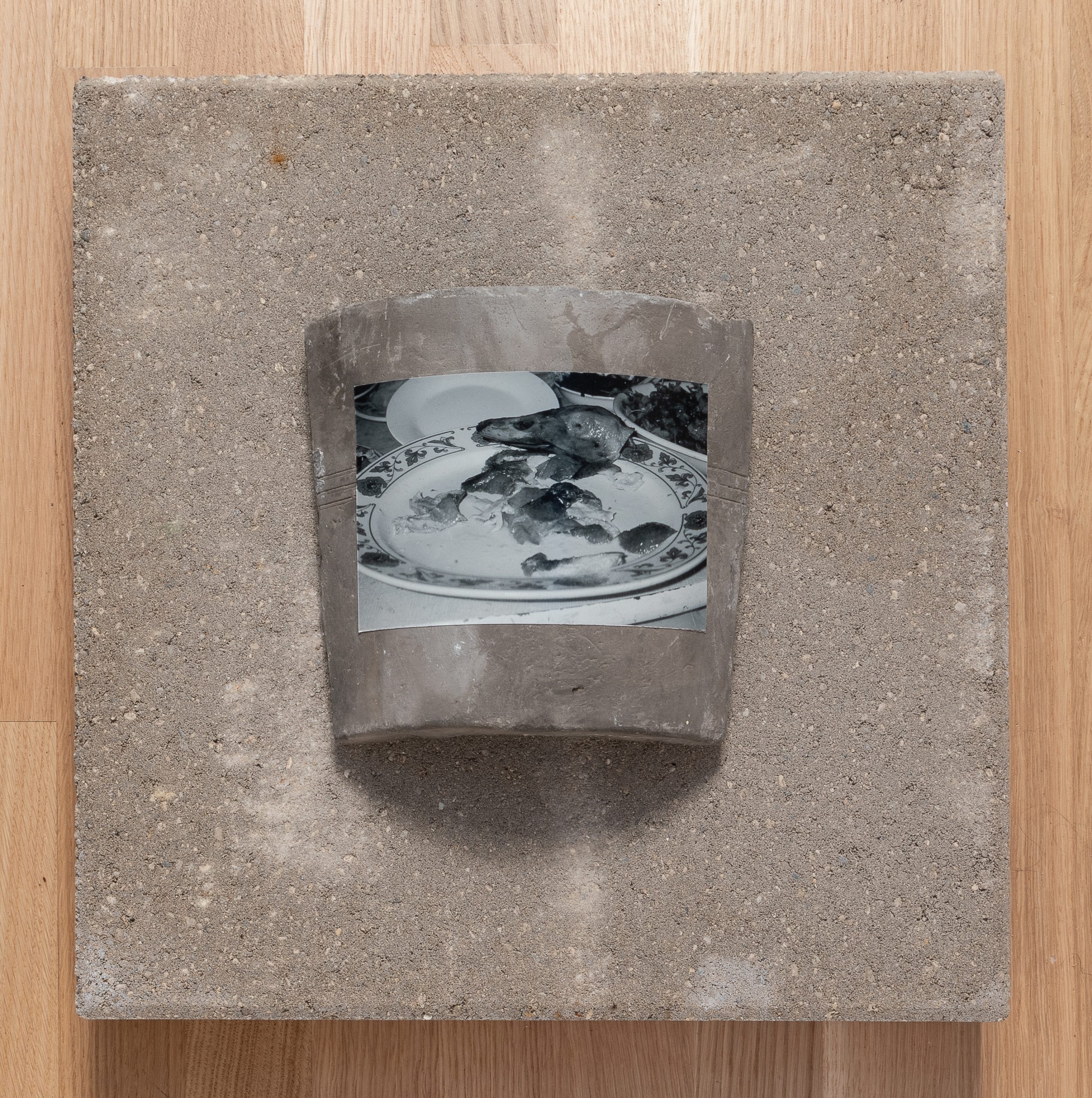

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.

/ Yin Xiuzhen, Transformation, 1997. Detail of individual tile.