-

Zhang Huan, Seeds, 2007

-

Cai Guo-Qiang, Mountain Range, 2006

-

Lin Tianmiao, Day-Dreamer, 2000

-

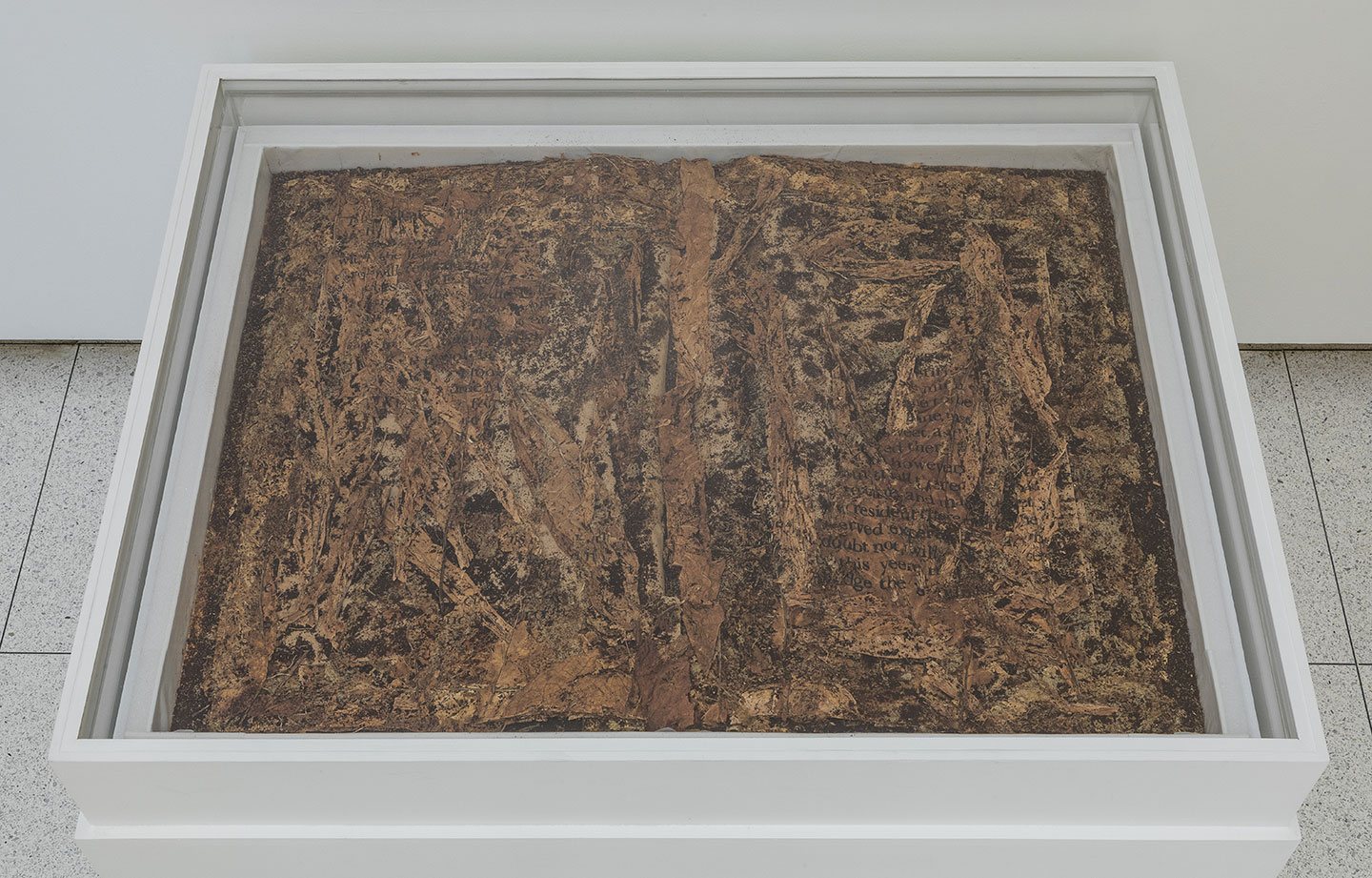

Xu Bing, Tobacco Book, 2011

-

Xu Bing, Traveling Down the River, 2011

-

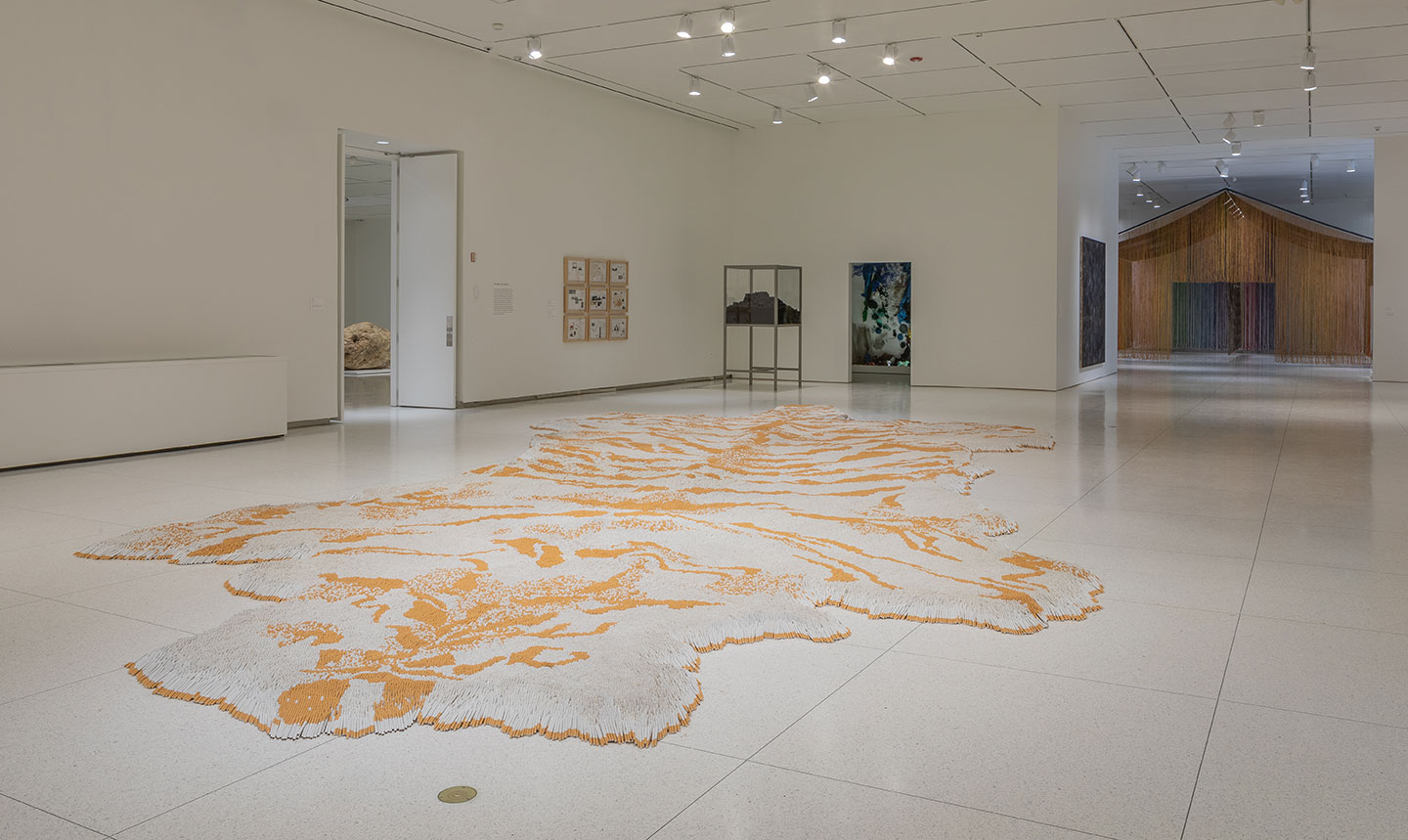

Xu Bing, 1st Class, 2011

-

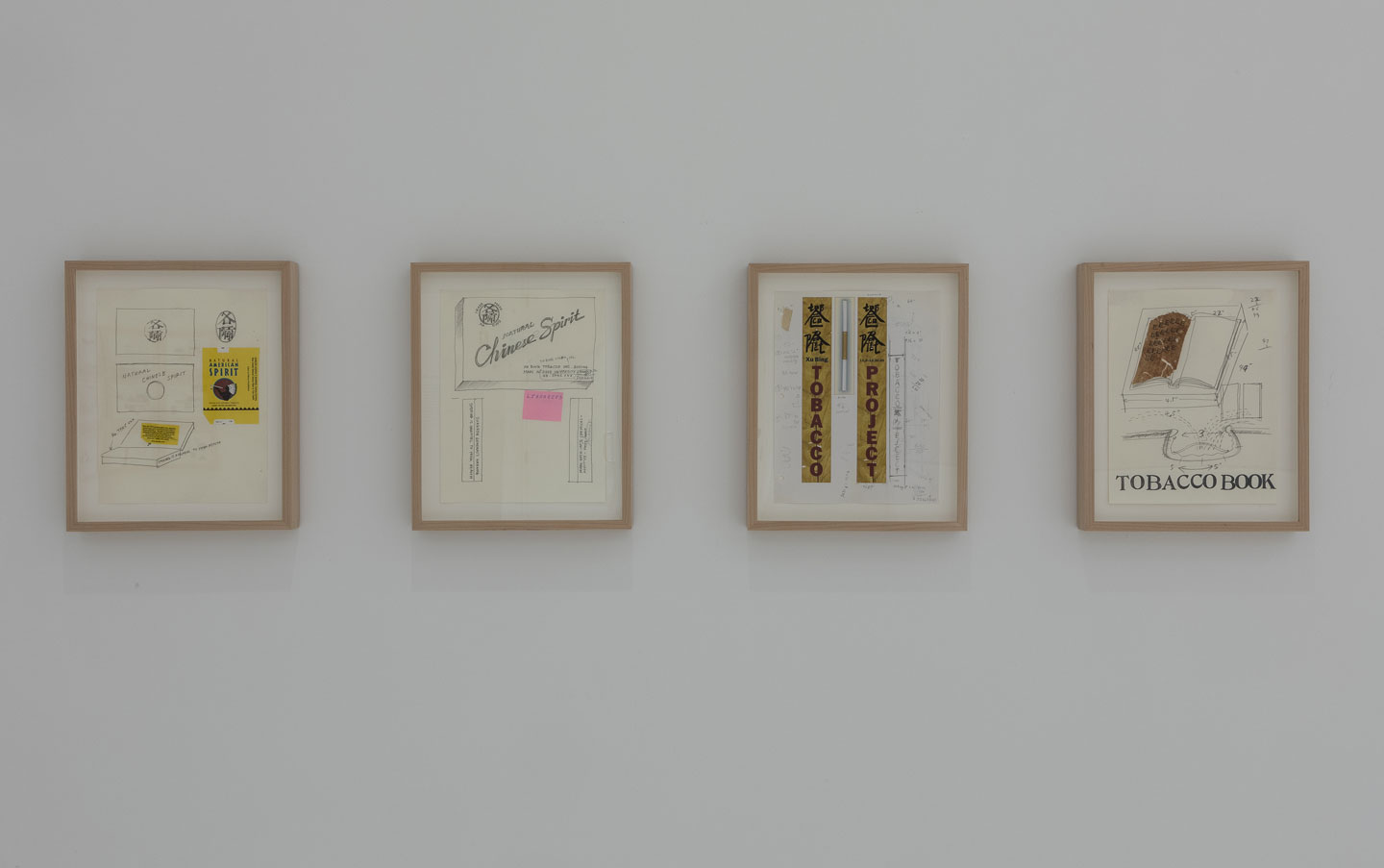

Xu Bing, Study sketches, 1999–2000

-

He Xiangyu, A Barrel of Dregs of Coca-Cola, 2009

-

He Xiangyu, A Barrel of Dregs of Coca-Cola, 2009

-

Gu Dexin, Untitled, 1989

-

Ai Weiwei, Tables at Right Angles, 1998

-

Huang Yong Ping, Devons-nous encore construire une grande cathédrale? (Should We Construct Another Cathedral?), 1991

-

Ma Qiusha, Wonderland: Black Square, 2016

-

Chen Zhen, Crystal Landscape of Inner Body, 2000

-

gu wenda, united nations: american code, 1995–2019

-

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Civilization Pillar, 2001/2019

-

Song Dong, Traceless Stele, 2016

-

Song Dong, Water Records, 2010

-

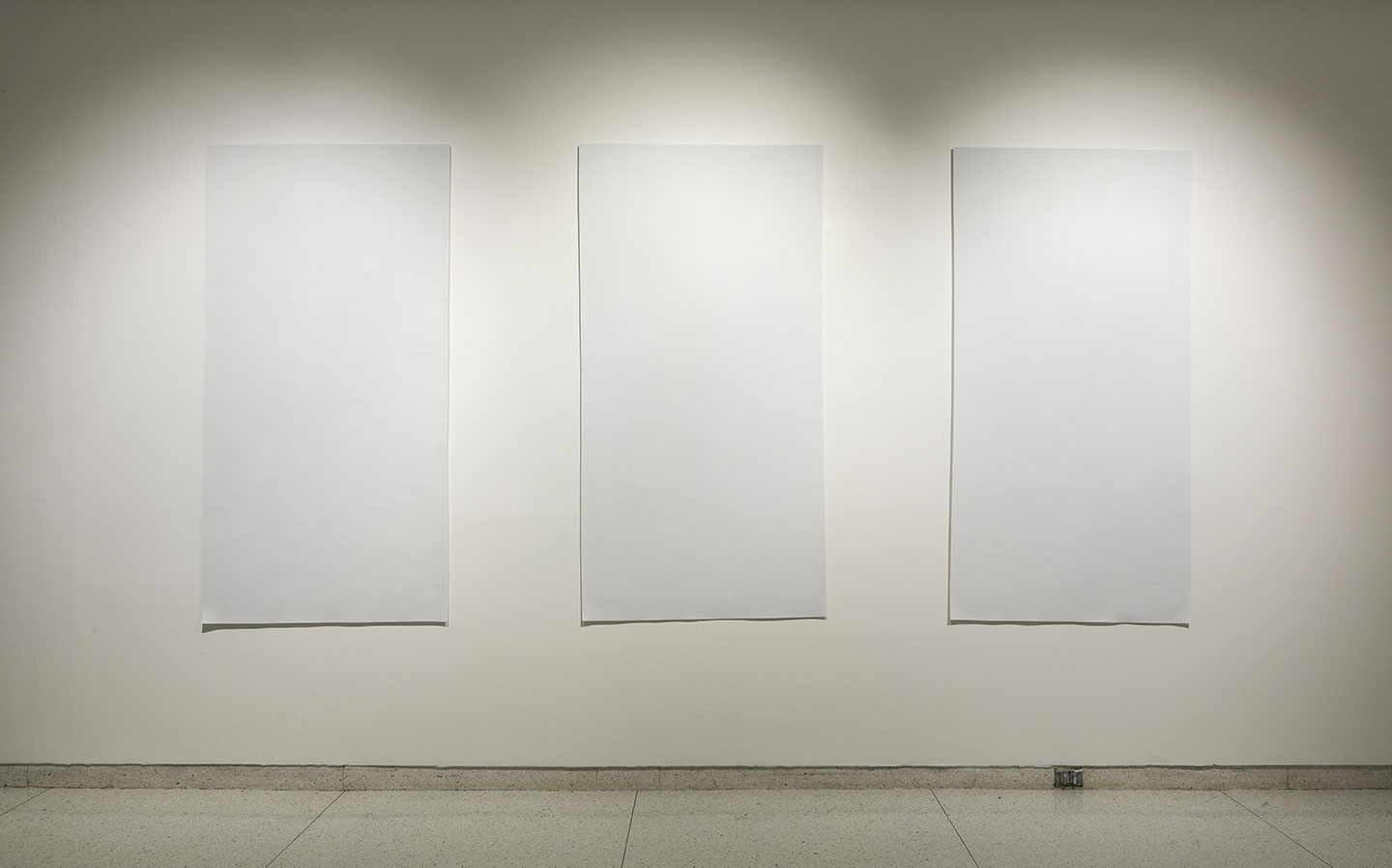

Liu Jianhua, Blank Paper, 2009–12

-

Zhan Wang, Gold Mountain, 2007

-

Zhan Wang, Beyond 12 Nautical Miles—Floating Rock Drifts on the Open Sea, 2000

Works on Main Floor

Use the gallery map to take a self-guided tour of The Allure of Matter at the Smart Museum of Art, or simply scroll to learn more about the exhibition’s constellation of highly individualized projects.

Zhang Huan, Seeds, 2007

Ash on linen

98 1/2 x 157 1/2 in. (250 x 400 cm)

Faurschou Collection

Zhang Huan began using ash as a material following a visit to the Longhua Temple in Shanghai, where he was struck by the ritual significance of the ash from joss sticks burned for prayers. As he described the experience, “The temple floor was covered with ash which leaked from the giant incense burner [ . . . ] These ash remains speak to the fulfillment of millions of hopes, dreams and blessings.” After collecting ash from temples throughout China, he transformed the ash by mixing it with water to make a primitive “paint” that could then be spread across the canvas. Although the earliest of these paintings were abstract, he shifted to figuration in 2007 when he began rendering Cultural Revolution-era photographs in ash. For Seeds, the artist’s studio assistants meticulously sorted ash into a palette of varying shades of gray and then reproduced an image of collective farming. The scene appears grand, but its cold, gray palette portends that the nationwide campaigns of the era were ultimately disastrous due to impossible demands for agricultural production.

Cai Guo-Qiang, Mountain Range, 2006

Gunpowder on paper, mounted on wood as six-panel screen

90 9/16 x 181 7/8 x 7/8 in. (230 x 462 x 2.2 cm)

Collection of the artist

Invented by ancient Chinese alchemists in their search for immortality, gunpowder now powers the destructive explosions of dynamite, bombs, and bullets. Intrigued by this complex history and its political implications, Cai Guo-Qiang has manipulated gunpowder to make elegant “explosion images” since the late 1980s. After many experiments, Cai developed an innovative method to control and contain these explosions to create gunpowder paintings. He first applies gunpowder in different variations according to an original sketch and then adds fuses and weighted cover sheets to manipulate the explosions. Channeling the violence inherent within the materials used, the images he produces—like this landscape of mountains—are at once powerful and delicate, random and controlled.

Lin Tianmiao, Day-Dreamer, 2000

White cotton threads, white fabric, and digital photograph

149 5/8 x 78 3/4 x 47 1/4 in. (380 x 200 x 120 cm)

Collection of the artist

In Day-Dreamer, Lin Tianmiao suspends hundreds of cotton threads along the outline of her self-portrait. The haunting silhouette suggests the impact of this labor-intensive process on her body. Since her early childhood, Lin has been fascinated with cotton thread. Her mother would tediously unravel the thread of white cotton gloves given to workers in state-owned factories to make new clothes and mend others. Reflecting on this task led Lin to think about the “corporeal punishment” women experience in their daily housework, and eventually inspired her to use thread to wrap, bind, and trace everyday objects. As she used more and more thread, her thinking about this type of punishment changed. She explains that while making the work, “I felt perfectly calm and psychologically at ease. The concept of ‘corporeal punishment’ changed: was I being punished or did I go looking for punishment?”

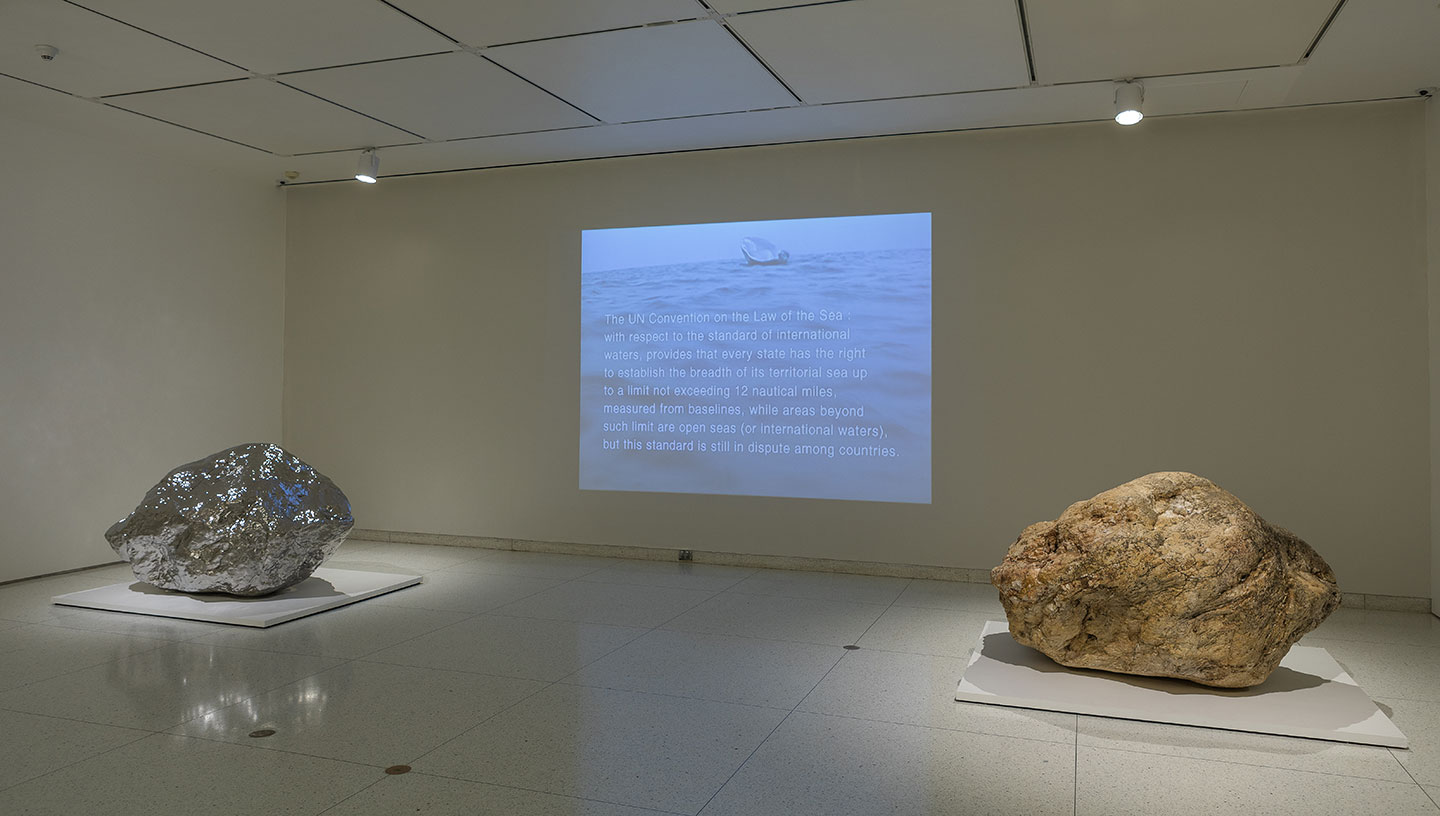

Xu Bing, Tobacco Book, 2011

Tobacco leaves, paper, and cardboard, rubber-stamped with passage from A True Discourse on the Present State of Virginia by Ralph Hamor (1615)

53 3/4 x 39 3/4 x 3 7/8 in. (136.5 x 101 x 9.8 cm)

Collection of the artist

The pages of Tobacco Book were made entirely from tobacco, and printed with a passage from A True Discourse on the Present State of Virginia, written by Ralph Hamor in 1615. A True Discourse describes the American Tobacco Company’s business operations in the British colony of Virginia and its expansion to China in a propagandistic fashion. When first exhibited, Xu Bing covered the book with tobacco beetles that slowly chewed away at the pages and the words written on them.

Xu Bing, Traveling Down the River, 2011

Burned cigarette on replica of the scroll Along the River During Qingming Festival 清明上河圖 by Zhang Zeduan 張擇端 (ca. 1080–1120)

Scroll: 10 x 275 in. (25 x 699 cm)

Collection of the artist

Traveling Down the River is a long cigarette, partially burned at one end, laid on top of a reproduction of the Song dynasty handscroll Along the River during the Qingming Festival, painted by Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145). Handscrolls are viewed over the course of their gradual unrolling; the burn present in this one alludes to the damage of smoking over time.

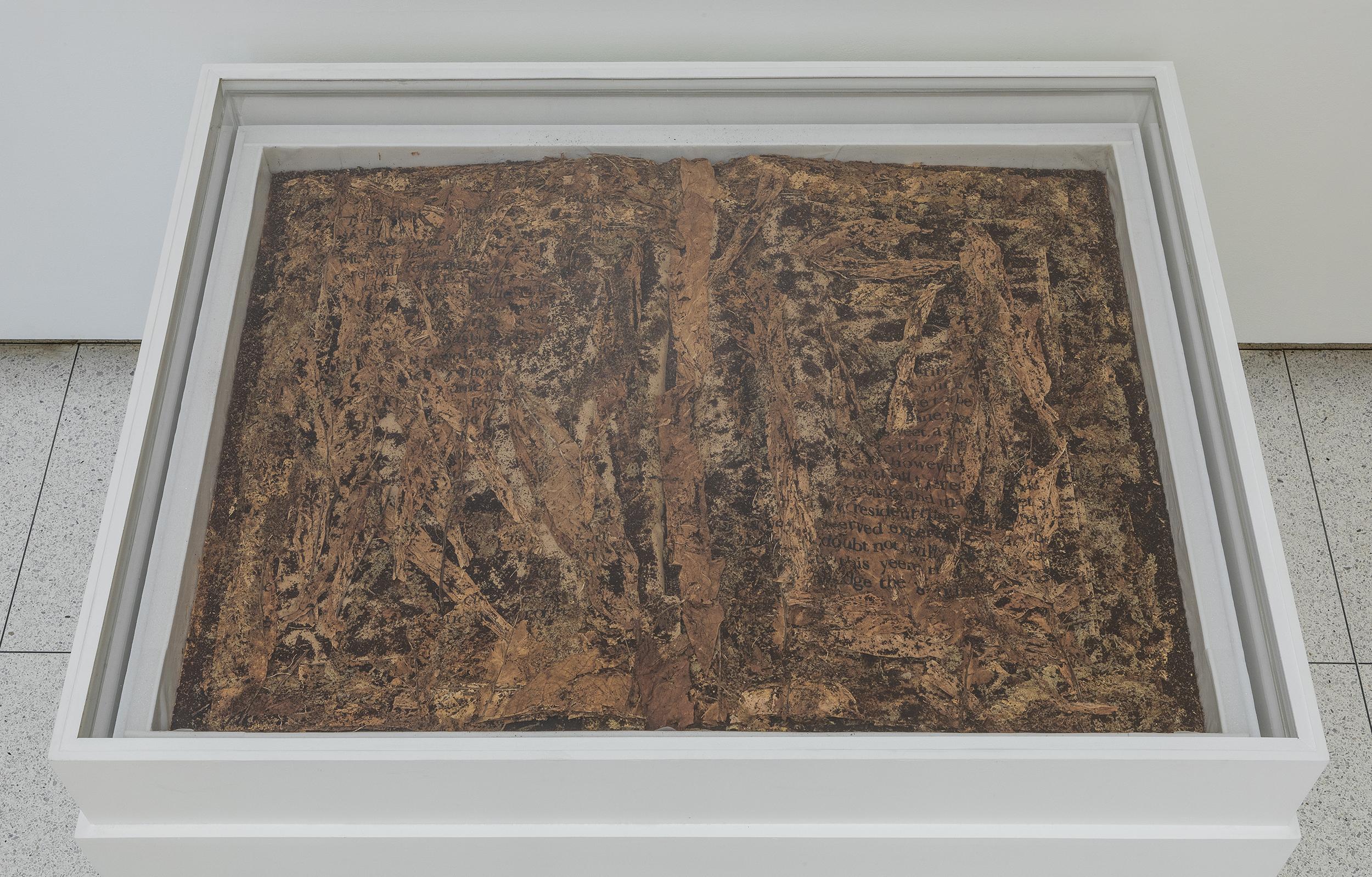

Xu Bing, 1st Class, 2011

500,000 “1st Class” brand cigarettes, adhesive, and carpet

480 x 180 in. (1219.2 x 457.2 cm)

Collection of the artist

1st Classis a tiger-shaped rug made of 500,000 1st Class-brand cigarettes. The work was inspired by a photograph of a tiger skin rug in a colonial home in Shanghai. Configured in the shape of this luxury item, the cigarettes are transformed into an extravagant lifestyle product that belies how dangerous smoking is to people’s health.

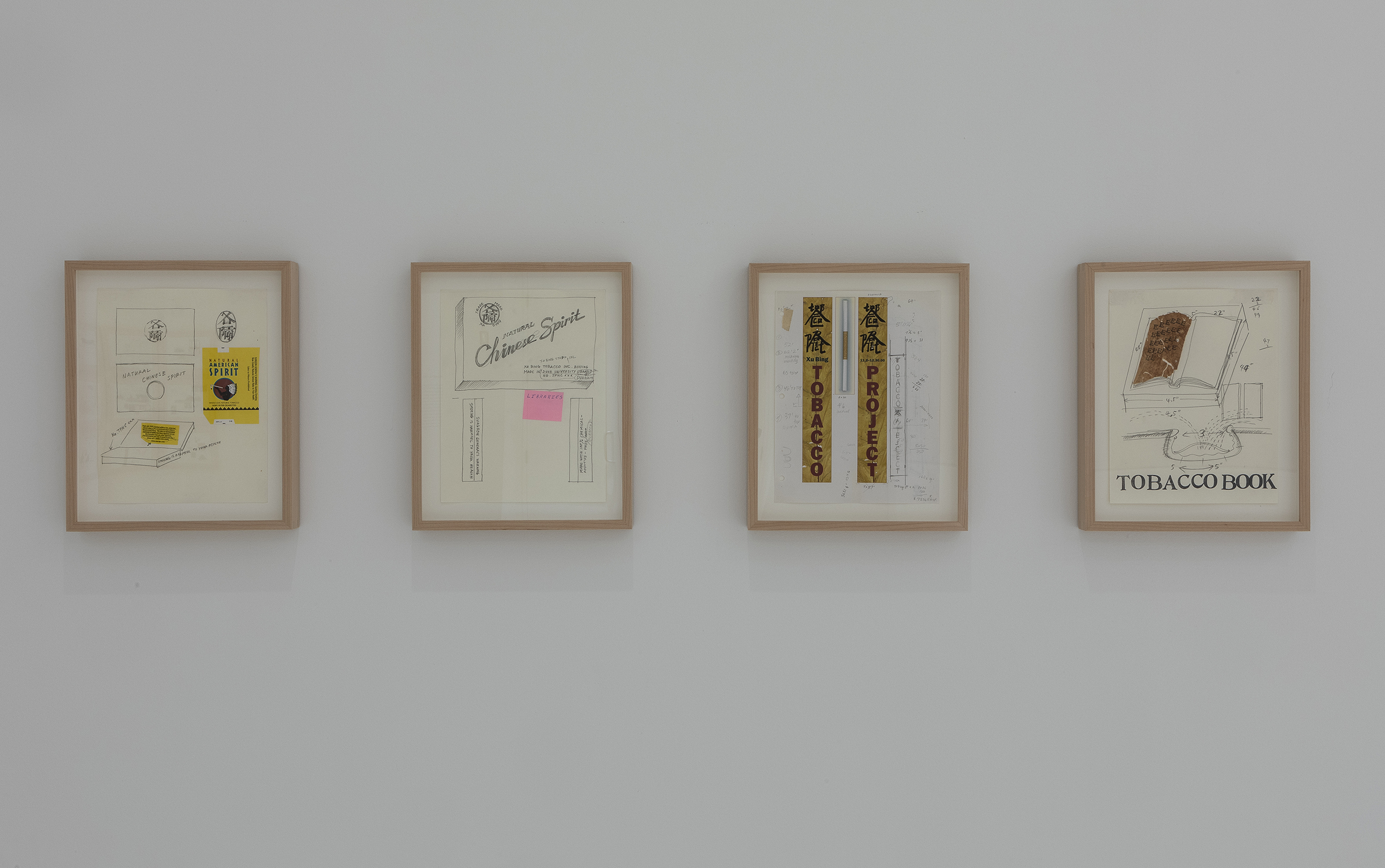

Xu Bing, Study sketches, 1999–2000

Study for Chinese Spirit I, 1999

Pencil and collage on paper

11 x 8 1/2 in. (28 x 21.6 cm)

Study for Chinese Spirit II, 1999

Pencil and collage on paper

11 x 8 1/2 in. (28 x 21.6 cm)

Study for Tobacco Book, 1999

Tobacco leaves, pencil, and ink on paper

11 x 8 1/2 in. (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

Study for Tobacco Project, 1999–2000

Pencil and collage on paper

11 x 8 1/2 in. (28 x 21.6 cm)

Collection of the artist

These four drawings are a selection from the artist’s preliminary sketches for Tobacco Project. Xu Bing collaged appropriations of cigarette packaging’s graphic design with materials he would later incorporate into the works’ final versions.

He Xiangyu, Cola, 9 Sketches, 2010

Ink, watercolor, barcodes, printed invoices, and photographs on paper

Each, framed: 16 x 20 7/8 in. (40.5 x 53 cm)

Rubell Family Collection, Miami

In these preparatory sketches, He Xiangyu outlines the production details and display designs for the artworks he made with soda resin as part of the Cola Project. In many of the sketches, He incorporates ephemera that inspired the project such as advertisements, a soda label, and documentary photographs.

He Xiangyu, A Barrel of Dregs of Coca-Cola, 2009

Coca-Cola resin, metal, and glass

82 5/8 x 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in. (210 x 100 x 100 cm)

Rubell Family Collection, Miami

This vitrine contains the resin of many gallons of Coca-cola that were boiled down during He Xiangyu’s Cola Project. Encased like a precious artifact, He Xiangyu elevates the glittering crystals as art and invites observation of their subtle texture.

Gu Dexin, Untitled, 1989

Melted and adjoined plastic

126 x 314 15/16 in. (320 x 800 cm)

Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon

In the early 1980s, Gu Dexin melted scrap pieces of plastic he took home from his job in a plastics factory in Beijing. The resulting melted plastic forms were some of the earliest examples of Material Art to be made in China. For Gu, plastic “was a new material and it was everywhere. Everything in the house was plastic: shoes, tablecloths, bowls, and utensils.” He was fascinated by its texture and versatility; it was malleable or hard, soft or brittle, and made in many different colors. Here in this room-sized installation, the abstractly molded plastic resists transformation into consumable objects and instead emphasizes its material form—contorted, organic, visceral, and raw.

Ai Weiwei, Tables at Right Angles, 1998

Tables from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

68 7/8 x 49 5/8 x 68 1/2 in. (175 x 126 x 174 cm)

Stockamp Tsai Collection

Using woodworking techniques that date from the 16th century, Ai Weiwei sutured two ancient tables collected from a Beijing antique market into a nonfunctional object. Part of his Furniture series, this work is an example of how Ai alters, transforms, and often destroys cultural relics and historic antiques. Balancing the tables at a perfectly perpendicular angle without using any nails or glue demonstrates the acuity of the craftsmen, yet this feat is countered as the table’s original function is destroyed. This construction subtly questions the value and authenticity of the original tables on display and their new worth now transformed into an art object.

Huang Yong Ping, Devons-nous encore construire une grande cathédrale? (Should We Construct Another Cathedral?), 1991

Table, stools, black-and-white photograph, and papier-mâché

Dimensions variable

Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris (acq. 1992)

To make this work, Huang Yong Ping washed texts in a washing machine, then piled the resulting pulp on tables and chairs. The photograph hanging on the wall portrays the event that these texts documented—a conversation between the artists Joseph Beuys, Enzo Cucchi, Anselm Kiefer, and Jannis Kounellis. During this conversation, Beuys memorably called for the reconstruction of European culture when he proclaimed, “Now we have to carry out a synthesis with all our powers, and build a new cathedral.” Whereas the four artists have repeatedly invoked cultural memory in their artworks, Huang used washing as a means to destroy cultural purity and grand historical narratives. As Huang once said, “washing books is not about making culture cleaner; rather, it makes its dirtiness more evident to the eye.”

Ma Qiusha, Wonderland: Black Square, 2016

Concrete, nylon stockings, plywood, resin, and iron

96 7/16 x 96 7/16 x 2 in. (245 x 245 x 5 cm)

Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Purchase, The Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions, 2019.4

Hidden beneath the stretched nylon skin of Wonderland: Black Square lay thick shards of rough gray cement. They fit together to create something between a mosaic and a tapestry, both fabric and stone, in varying shades and sheens of black. A sense of tension—created here by stretching fabric over cement pieces— is a major component in much of Ma Qiusha’s work. The title of the series recalls the massive Wonderland Amusement Park once located at the outskirts of Ma’s hometown of Beijing. Begun during Ma’s childhood in the 1990s, construction of the park was never completed; it was quietly demolished two decades later. While the work’s title evokes development and decay, its materials point to something else. Ma’s use of different types of pantyhose alludes to the succession of generations of women in China: the thick, flesh-colored pantyhose that her mother and grandmother wore contrasts with the multi-hued ones younger generations could buy.

Chen Zhen, Crystal Landscape of Inner Body, 2000

Crystal, glass, and metal

Table: 37 3/8 x 27 5/8 x 74 13/16 in. (95 x 70 x 190 cm)

Private collection, Paris, courtesy of Galleria Continua, San Gimignano/Beijing/Les Moulins/Habana

Crystal Landscape of Inner Body evokes the centuries-old Daoist concept of “Internal Alchemy,” a healing practice involving the visualization of the human body. By meditating on each internal organ and body part, a process of purification could be initiated. Fascinated by medicine, Chen Zhen once mused: “When one’s body becomes a kind of laboratory, a source of imagination and experiment, the process of life transforms itself into art.” In Crystal Landscape, Chen renders his own internal organs in glistening clear crystal. This purity contradicts the body’s own contamination. It is one of the last pieces Chen created before his untimely death from cancer in 2000.

gu wenda, united nations: american code, 1995–2019

Human hair

Dimensions variable

Commissioned by the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Seattle Art Museum; and Peabody Essex Museum for the exhibition, The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China.

When gu wenda first moved to the United States in the early 1990s, he began experimenting with different bodily materials. In 1993, he intermingled and felted strands of hair collected from around the world into a large-scale installation. Since this first monument, gu has continued to use hair as the main material in his ongoing united nations series.

For american code, colorful braids of hair form a tent enclosing a flag, which is similarly made from hair. By bringing together hair from disparate groups of people from around the world, gu evokes the United States’ identity as a nation of immigrants. However, the flag hanging in the center of the monument does not belong to any particular country; rather, it is made up of a generic star and stripes formed by pseudo-scripts. Like the Tower of Babel, gu’s american code not only demonstrates the universality of the human condition but also evinces the fundamental heterogeneity of cultures around the world.

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Civilization Pillar, 2001/2019

Human fat, stearic acid, paraffin wax, petroleum jelly, and metal support

Overall: 145 11/16 x 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 in. (370 x 100 x 100 cm)

Commissioned by the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago

Civilization Pillar is made from human fat that was collected from plastic surgery clinics, chemically purified and altered into a wax- like substance, and then cast as a gleaming column. Sun Yuan and Peng Yu are known for their deliberate use of unconventional and often challenging materials. For the artists, human fat is the physical manifestation of excess: unused food energy stored as deposits on the body. The liposuction process that extracted the fat adds another layer of meaning to the material; excess fat was eliminated through a cosmetic procedure that caters to vanity and modern ideals of beauty. Considering the material to be “a by-product of our contemporary society,” the artists display the reclaimed fat as a monument to civilization.

Song Dong, Traceless Stele, 2016

Metal stele, heating device, water, and Chinese brushes

92 1/2 x 59 1/16 x 39 3/8 in. (235 x 150 x 100 cm)

Collection of the artist, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Used as memorials in China for centuries, steles feature carved inscriptions that relay important information about the people or events they were meant to commemorate. Here, the stele is blank; you are invited to write your own message on the hard stone face using a brush and water. The water quickly dries, erasing the message and creating a fleeting memorial that contrasts with ancient steles that have preserved their inscriptions for centuries. Fascinated by Daoist notions of impermanence, Song employs the translucency and formlessness of water to explore what cannot be seen or said. When first shown in China, the disappearing texts inspired political interpretations by providing a space of free speech.

Song Dong, Water Records, 2010

Four-channel video projection, running times variable

Collection of the artist, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Since the early 1990s, Song Dong has repeatedly used water as a signature material in his practice. For the earliest of these works, Writing Diary with Water (1995), Song kept a daily record of his activities written in water on a dark gray stone. In Water Records, brushstrokes of figures and characters begin to evaporate and disappear before the artist can finish delineating them. According to Song, these ephemeral water drawings were meant to be “random fragments of memory, imprecise, incorrect, incomprehensive, and incomplete.” By not rendering any concrete, permanent representation, Song’s performance explores the transience of water, a material that leaves no record behind.

Liu Jianhua, Blank Paper, 2009–2012

Porcelain

Each: 79 1/8 x 40 1/2 x 3/8 in. (201 x 103 x 0.8 cm)

Collection of the artist, courtesy of Pace Gallery

Fired at over 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, porcelain is known as one of the most delicate and difficult artistic materials, often demanding a great deal of technical mastery to produce. In Blank Paper, Liu Jianhua took on the challenge of making porcelain as thin as paper. When recalling the moment of inspiration for this work, Liu said:

The challenge shouldn’t be displayed upon the surface, but should become part of the object’s intrinsic quality. One day I was making drawings on a paper pad. It suddenly occurred to me that I could simply make a piece of blank paper in porcelain, lying quietly in front of you.

Leaving each Blank Paper unglazed and unmarked, Liu invites his viewers to reflect on its paradoxical appearance and fill its surface with their thoughts.

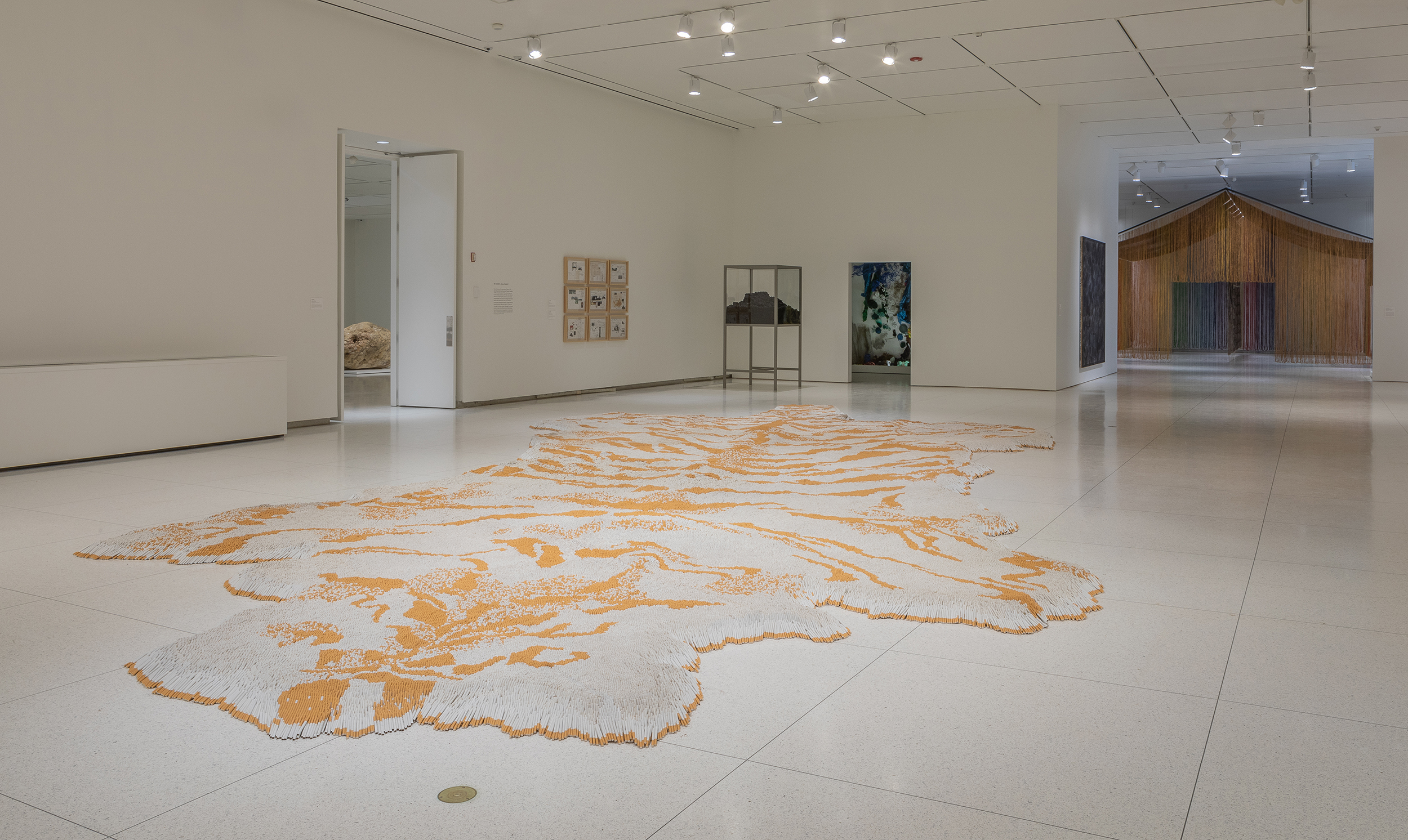

Zhan Wang, Gold Mountain, 2007

Stone and stainless steel

Stone: 42 x 50 x 63 in. (106.7 x 127 x 160 cm)

Stainless steel: 42 x 50 x 63 in. (106.7 x 127 x 160 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Haines Gallery

Sculptor Zhan Wang is best known for making stainless steel rocks inspired by gongshi, or scholars’ rocks. During the Song dynasty, members of the literati class collected rocks that had been transformed in extraordinary ways so that their natural shapes presented art-like forms. As if to reverse this tradition, Zhan produces metal replicas of found rocks by pounding thin sheets of stainless steel against their surfaces. The steel sheets are then welded together and polished to a reflective shine, a process that requires not only brute force but also the precision of a fine jeweler.

For Gold Mountain—a title evoking the Chinese word for San Francisco, jiujinshan (literally, “Old Gold Mountain”)—Zhan chose a boulder from the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, an area where thousands of Chinese immigrants broke rocks and panned for gold in the mid-19th century. Presenting his Sierra rock and its mirror-like replica side by side, Zhan invites us to reflect upon art-making as an act of imitation, while comparing the labor of the artist to that of a miner during the Gold Rush.

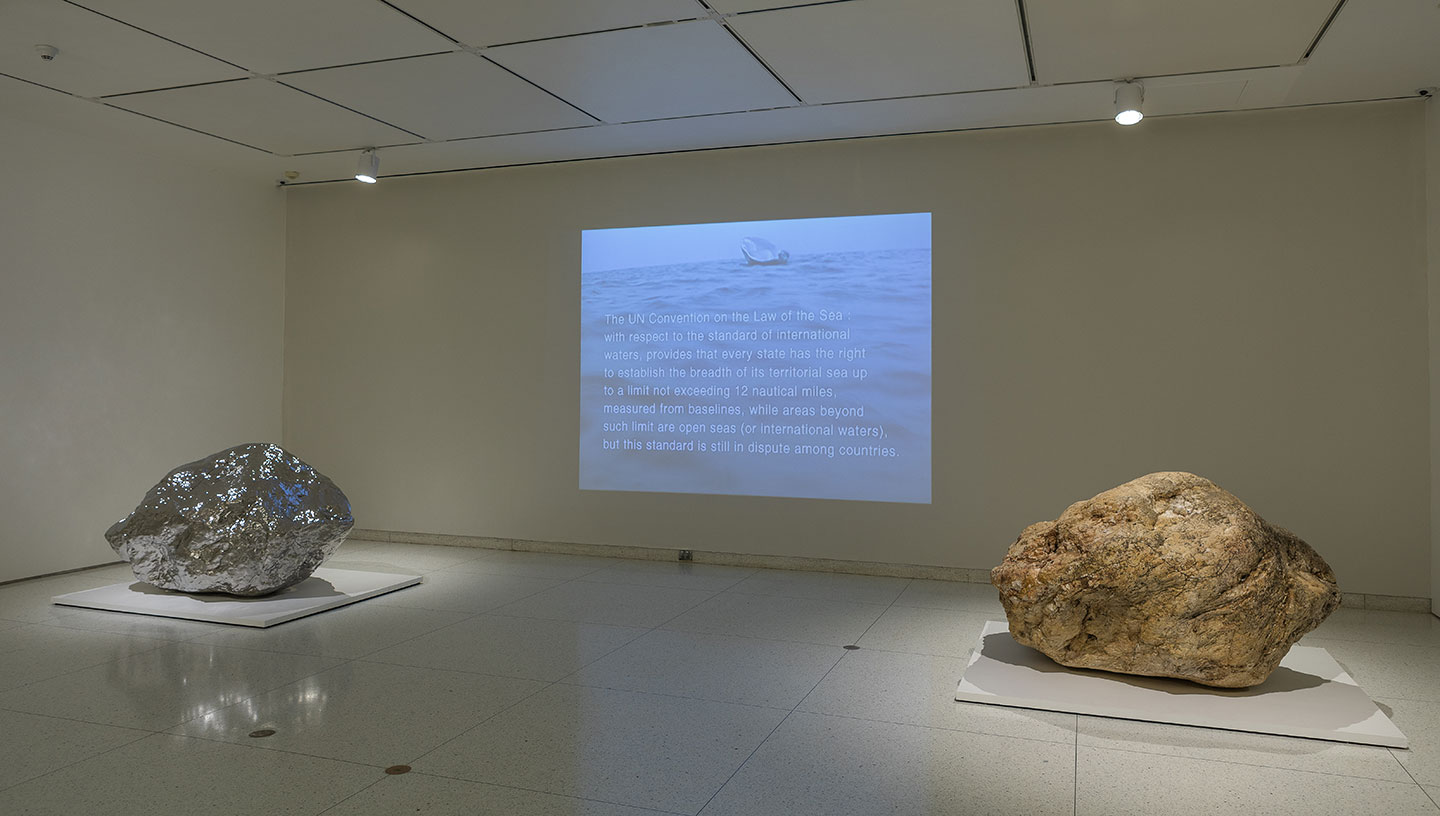

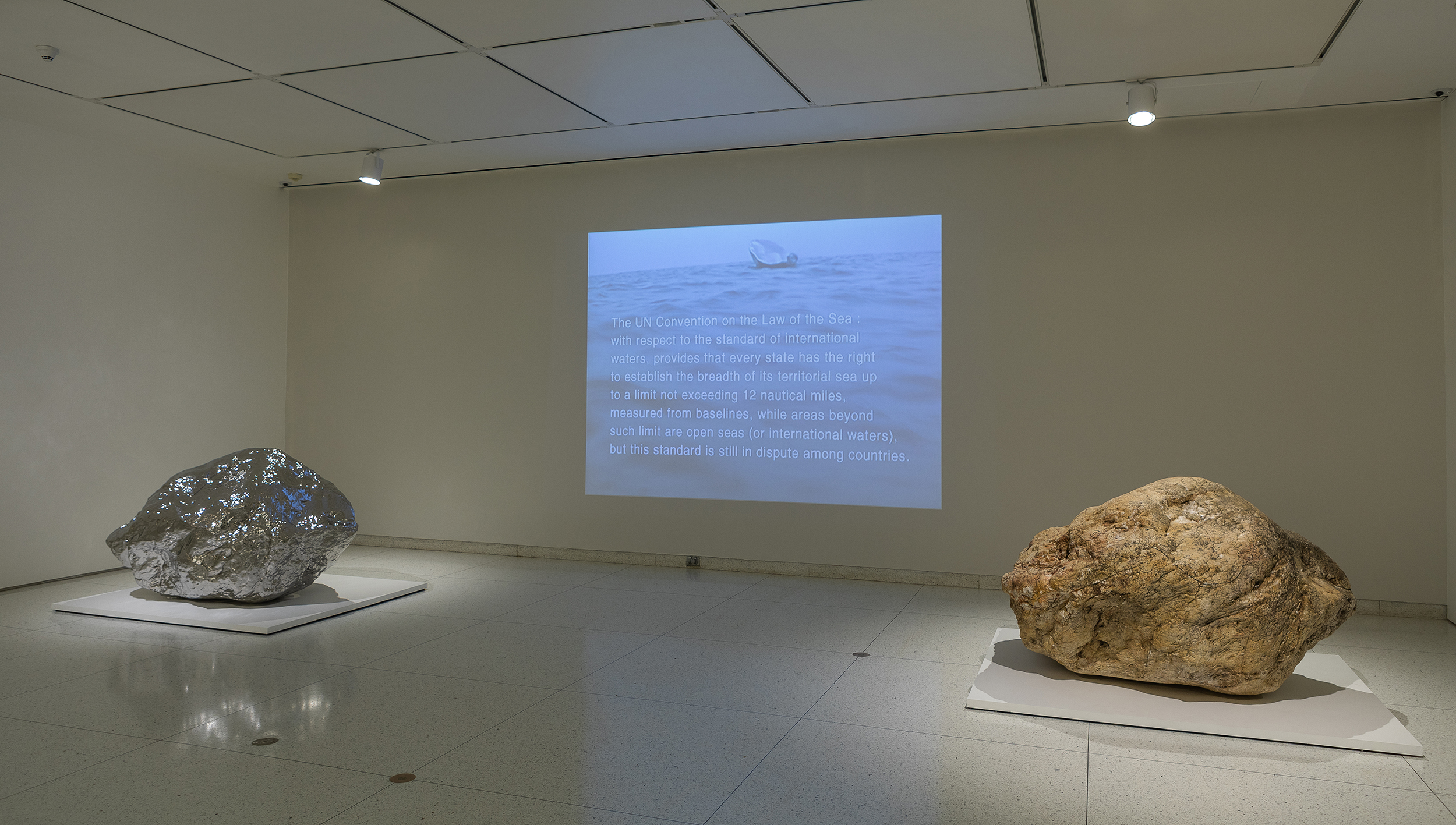

Zhan Wang, Beyond 12 Nautical Miles—Floating Rock Drifts on the Open Sea, 2000

Single-channel video, 8:36 minutes running time

Collection of the artist

In this performance project, Zhan Wang carefully molded a hollow stainless steel rock and left it to float in the open seas. The work’s title refers to the point beyond which any country can claim open waters as its territory. Left to drift wherever the currents take it, the rock has the following passage inscribed in five different languages upon its surface:

This is a piece of art created specifically to be exhibited in the open sea. If by any chance you pick it up, please put it back into the ocean. The artist thanks you from afar.