-

Liu Jianhua, Black Flame, 2017

-

Liang Shaoji, Chains: The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Nature Series, No. 79, 2002–7

-

Jin Shan, Mistaken, 2015

-

Sui Jianguo, Kill, 1996

-

Hu Xiaoyuan, Ant Bone IV, 2015

-

Hu Xiaoyuan, Ant Bone V, 2015

-

Zhang Yu, Fingerprints, 2008

-

Wang Jin, Chinese Dream, 2006

-

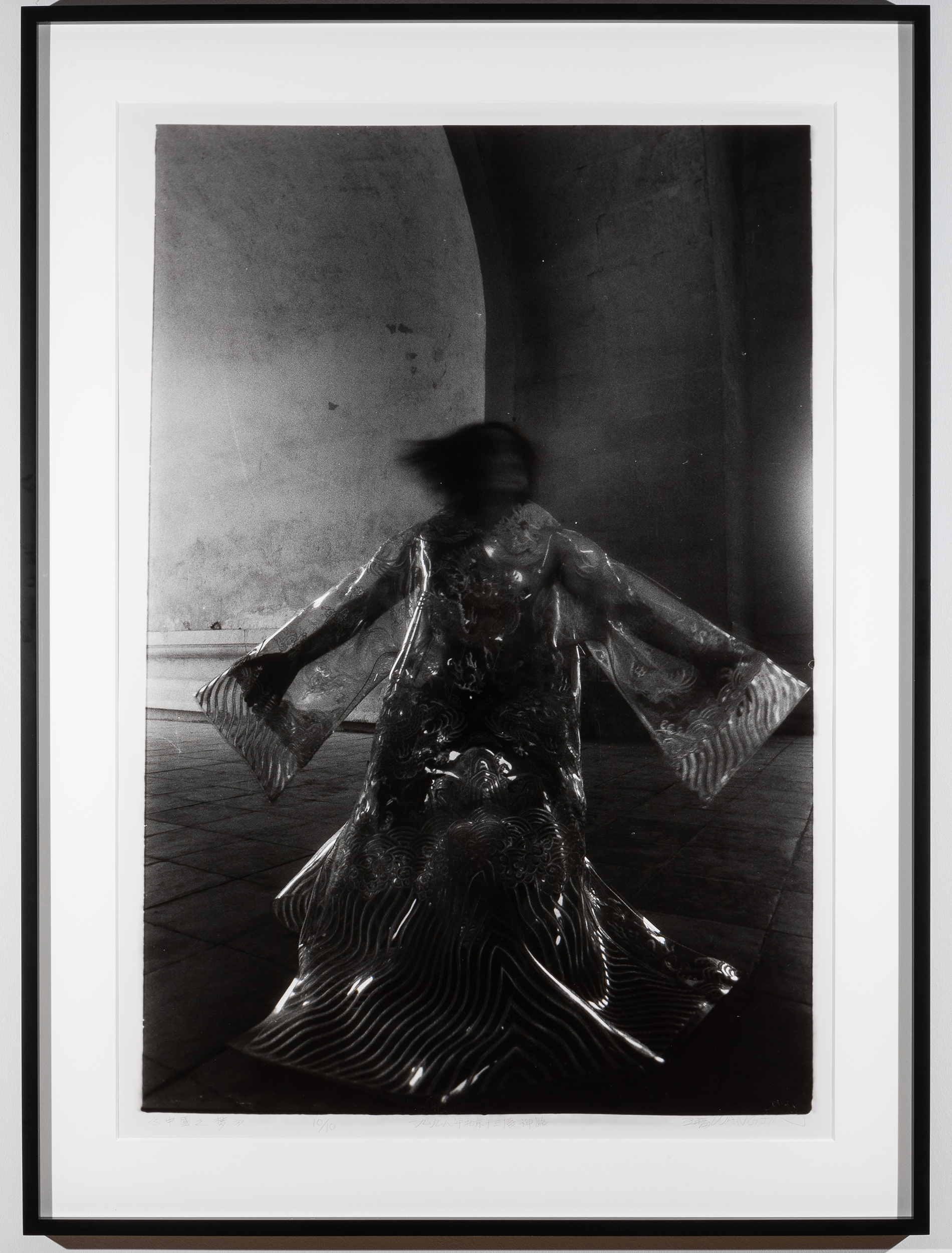

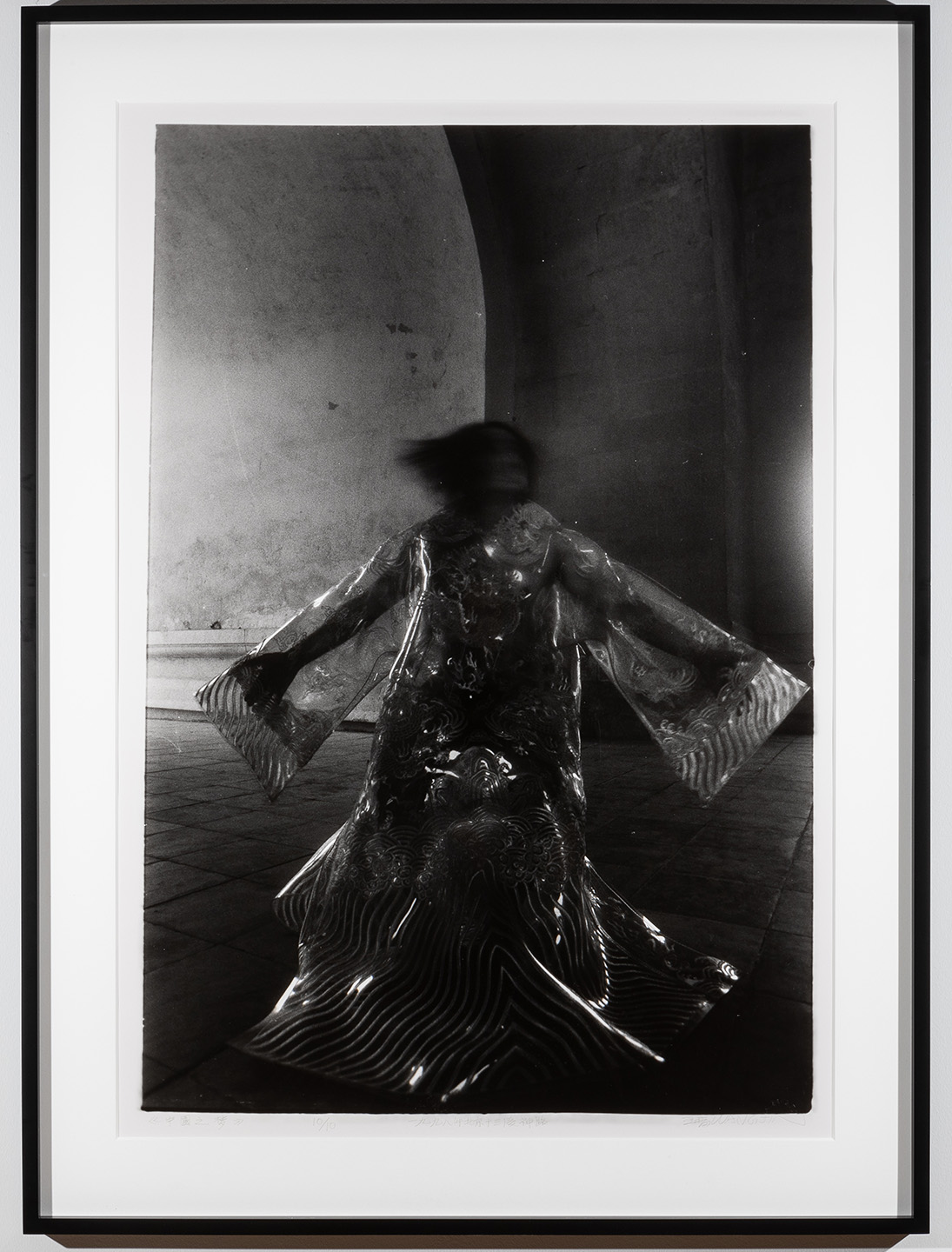

Wang Jin, A Chinese Dream, 2006

-

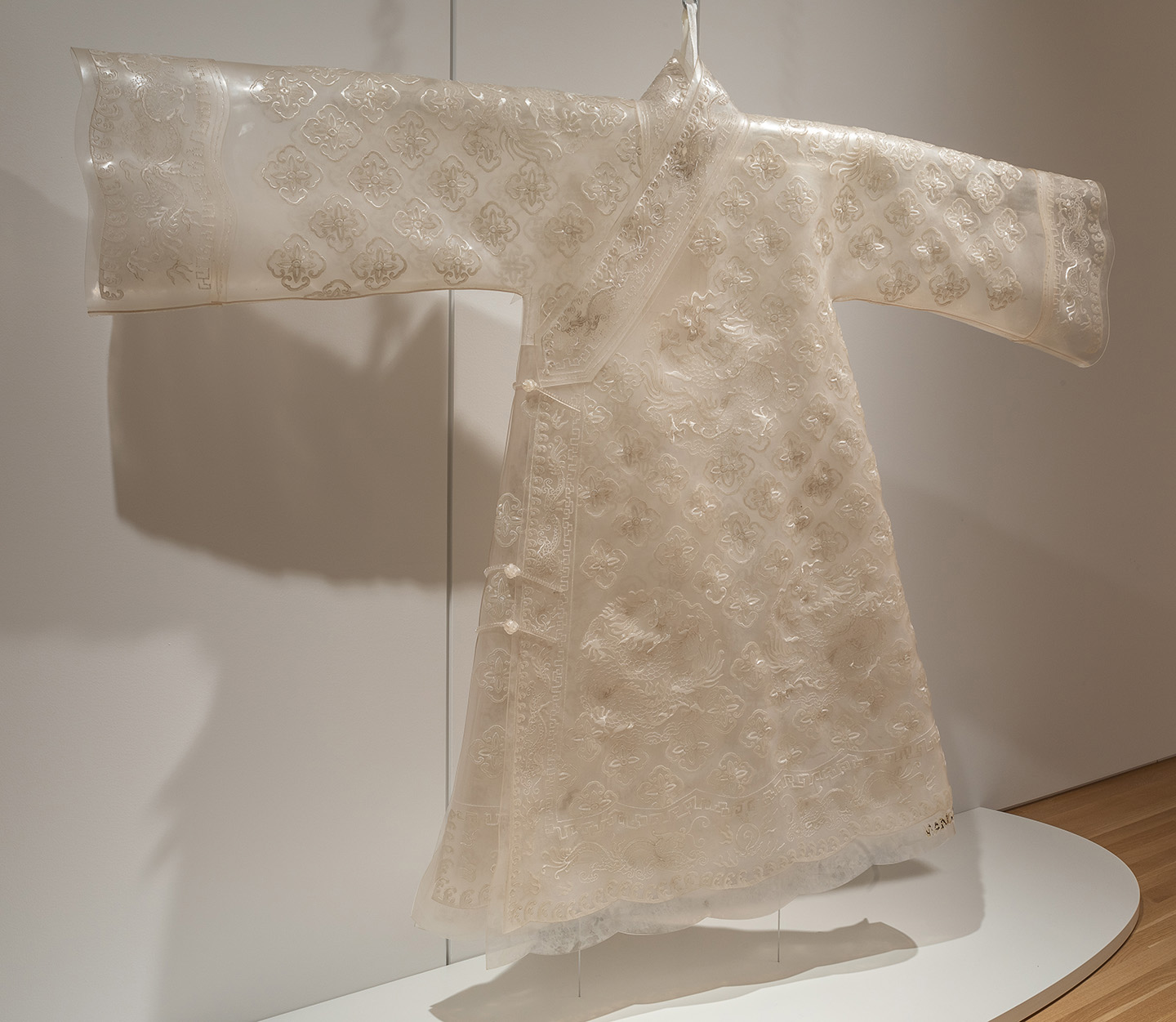

Wang Jin, The Dream of China: Dragon Robe, 1997

-

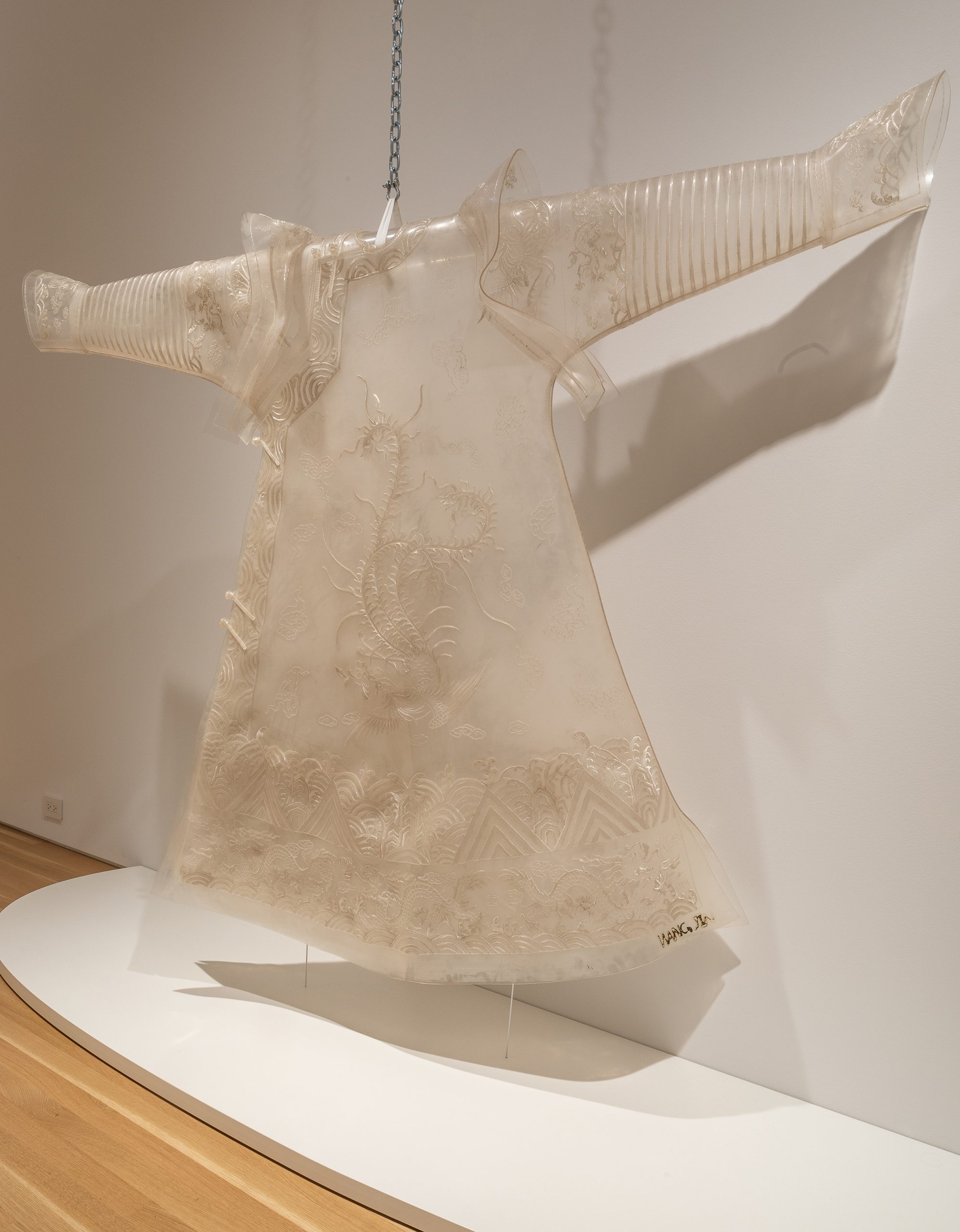

Wang Jin, Dream of China No. 2, 1998

Works on Main Floor

Liu Jianhua, Black Flame, 2017

Porcelain

Dimensions variable

Collection of the artist, courtesy of Pace Gallery

In this work, 8,000 black flames span the gallery floor like a rapidly spreading fire. Made of porcelain, Black Flame foregrounds the extraordinary characteristics of its materiality: porcelain is the only ceramic material that becomes impermeable to water after its first firing. Too multitudinous to be extinguished, these flames are similarly resilient, unable to be destroyed by water. Since the 1990s, Liu Jianhua has explored various properties of porcelain in his artistic practice, often creating installations as expansive as Black Flame that challenge the distinctions between craft traditions and contemporary art.

Liang Shaoji, Chains: The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Nature Series, No. 79, 2002–7

Polyurethane, colophony, iron powder, silk, and cocoons

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist and ShanghART Gallery

Liang Shaoji has repeatedly said “I am a silkworm.” For over 25 years, Liang has raised silkworms and trained them to spin silk onto different objects in his Nature series. Here, hollow chains are covered in delicate, white raw silk. The silkworms not only create the material but also become live participants, stand-ins for the artist. With works like Chains, Liang blurs the boundaries between his role as an artist and that of the silkworms with whom he co-creates this artwork, opening larger questions of the distinction between art and nature.

Furthermore, his fascination with silk is rooted in the Chinese psyche: Chinese legends connect the invention of silk-making with the creation of Chinese civilization. It is said that the legendary Yellow Emperor or his wife, Lady Xiling, actually discovered how to raise silkworms and spin silk.

Jin Shan, Mistaken, 2015

Wood and plastic

76 1/4 x 35 1/2 x 39 1/2 in. (193.7 x 90.2 x 100.3 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and BANK/MABSOCIETY

For years, Jin Shan has experimented with how to mold plastic into figures and forms that could retain the appearance of melting plastic even after the material had hardened into a shape. Mistaken foregrounds this dynamism and movement. Fists punch out from the plastic face of a heroic Communist worker, yet the plastic appears to disintegrate into fine strings. The sculpture’s lower part is made up of an aggressive arrangement of wood slats. The wooden pieces, chopped by Jin himself, are made from the wooden doors of old, demolished houses on the outskirts of Shanghai. The dramatic contrast of the two materials—the wooden relics of old buildings and the plastic Cultural Revolution imagery—suggests that memories of China’s past are fragmented.

Sui Jianguo, Kill, 1996

Rubber and iron nails

Dimensions variable; unrolled: 354 3/8 x 24 3/8 in. (900.1 x 61.9 cm)

Collection of the artist, courtesy of Pace Gallery

A single sheet of rubber with 300,000 nails driven through it, Kill both exposes the incredible resilience of rubber as a material and demonstrates how abstracted forms can manifest broader political significance. Sui describes it this way:

It surprised me that even a small piece of rubber can bear a great many nails without altering its shape and qualities. What is more, by incorporating so many nails into its own body the rubber sheet has changed from a passive and receptive object to an active and aggressive one. This makes me think about our nation and myself. All throughout this century—since the establishment of the PRC, the opening up after the Cultural Revolution, and the June Fourth Movement—the Chinese people have shown great strength of endurance. But pliability also means alienation; we all have this ability to survive.

Hu Xiaoyuan, Ant Bone IV, 2015

Chinese catalpa wood, ink, raw silk (xiao), paint, and iron nails

82 11/16 x 126 x 23 7/16 in. (210 x 320 x 59.5 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Beijing Commune

Hu Xiaoyuan, Ant Bone V, 2015

Chinese catalpa wood, ink, raw silk (xiao), paint, and iron nails

73 7/16 x 31 7/8 x 75 3/16 in. (186.5 x 81 x 191 cm)

Courtesy of the artist and Beijing Commune

The frameworks of Hu Xiaoyuan’s Ant Bone series are made of scrap wood from dismantled architectural structures. Without a single nail, she builds geometric structures using mortise-and-tenon joints, used for centuries in Chinese woodworking. On each form’s interior, Hu carefully covers the wood with her signature paintings on silk. With a technique she developed in 2008, she meticulously traces the wood’s grain on a piece of raw silk (xiao) to make a seemingly perfect copy. She then paints over the surface of the wood to obscure the real grain before affixing the painted silk tracing with tiny nails. Enveloping the painted wood, the silk reproduces the wood’s grain, scars, and surface markings—the physical recordings of change over time. The interplay between the wood and the silk subtly draws out tensions between what is old and new, used and raw, original and copied.

Zhang Yu, Fingerprints, 2008

Longjing water on xuan paper

Three scrolls, 275 1/2 x 43 1/4 in. (699.8 x 109.9 cm) each

Collection of the artist, Beijing

From a distance, the scrolls of this installation appear as if they are made of plain paper without any pictures or writing. With a closer look, however, the surface texture becomes visible: they are covered with the impressions of thousands of individual fingerprints. Zhang Yu created these impressions by dipping his index finger in water, then tenderly pressing it to the paper’s surface; the spot he touched became wet and darkened slightly, but soon dried, leaving only a subtle, sunken dot. Using neither ink nor brush, Zhang creates works that bracket image-making in order to forge a synergetic relationship between painting, installation, and performance with the human body. His use of water as a material is highly significant in this process; it does not serve a direct representational purpose, but instead is an “empty sign” that registers what remains after he lifts his hand from the paper.

Wang Jin, Chinese Dream, 2006

PVC with embroidered fishing thread

67 x 82 1/2 x 5 in. (170.2 x 209.5 x 12.7 cm)

Pizzuti Collection

Wang Jin, A Chinese Dream, 2006

PVC with embroidered fishing thread

67 x 82 1/2 x 5 in. (170.2 x 209.5 x 12.7 cm)

Private collection, New York

Wang Jin, The Dream of China: Dragon Robe, 1997

Polyvinyl chloride and vinyl filament

71 x 78 x 15 in. (180.3 x 198.1 x 38.1 cm)

The Farber Collection

Wang Jin, Dream of China No. 2, 1998

Black and white photograph

50 13/16 x 38 3/16 in. (129 x 97 cm)

Copyright Wang Jin. Photo courtesy of Pékin Fine Arts

Wang Jin’s imperial robes and theatrical costumes levitate like specters of a bygone age. Such garments traditionally bear encoded symbols, such as five-clawed dragons representing the imperial house or multicolored waves, rocks, and clouds that present the universe under the ruler’s sway. Here, rich silks, golden threads, and opulent brocades are replaced with a common industrial material, PVC plastic.

Wang initially created a Chinese Dream for one of the first domestic auctions of Chinese art in Beijing in 1997. He chose to make “fake” Peking Opera costumes that catered to the tastes of foreign art collectors. During the 1990s, Peking Opera had become a tourist attraction which was notorious as a highly superficial cultural experience. By choosing a modern, translucent material for his robe, Wang captured the spurious, empty notions of “cultural authenticity” foreigners expected of Chinese art during this time.